Any conversation about the greatest Yooper of all time pretty much begins and ends with Timber Tony.

Tony Calery was born in Sault Ste. Marie in 1918 and picked up the nickname “Timber Tony” because he mostly made his living as a self-employed lumberjack. He chopped firewood on his property and cut down trees in town suffering from Dutch Elm disease.

By the time he was in his 30s, he was already a local legend, but during the summer of 1964, he became a legend across the country when he decided to row a boat from Sault Ste. Marie to New York City—some 2,000 miles—in less than 80 days.

Why? Just for the hell of it.

Don Cooper, a longtime county commissioner in Chippewa County, grew up a few houses down from Timber Tony on Portage Street.

“Oh, yes, he was tough,” Cooper said. “He always wore a shirt that was unbuttoned and had the sleeves rolled up, even in the winter. And he was strong. I would watch him pick a motor block up from the ground with his bare hands and put it in the truck.”

When he wasn’t cutting down trees or picking up motor blocks, he was hanging out in one of the local establishments.

“He would go to different bars and have a shot or arm wrestle somebody,” Cooper said. “He was always chewing tobacco or smoking cigars. And he always wore that same kind of (porkpie) hat. He had a bunch of them in different colors.”

While everyone in the Soo knew Timber Tony, he didn’t gain fame outside of town until he started rowing.

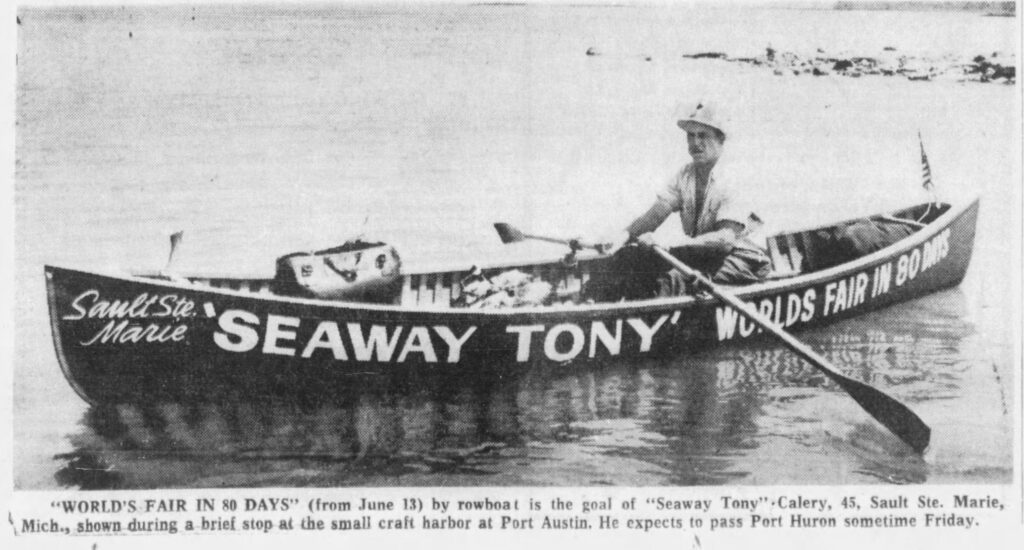

Seaway Tony

He had no particular affinity for water or rowing— he couldn’t even swim—but he took it up in 1958 when a local radio announcer in the Soo bet him that he couldn’t row a boat all the way around nearby Sugar Island.

“It’s about 55 miles around there,” Timber Tony told a reporter. “So I got a guy to come with me. He fished while I rowed. We made it in about a day and a half.”

That led to another challenge in 1962, when he rowed a boat all the way from Sault Ste. Marie to Muskegon—about 400 miles—as part of the Muskegon Seaway Festival. It took him 18 days. He got a lot of publicity along the way, and the folks in Muskegon treated him like a king when he got there.

That trip gave him a new nickname, too: Seaway Tony.

No one was too shocked two years later when he announced his row to New York.

The World’s Fair was going on that summer, and the movie “Around the World in 80 Days” had come out just a few years earlier. That gave Timber Tony a reason to take the trip with the “80 days” hook. He figured he’d get a lot of attention for the feat, and he was right.

“Everything he did was to get attention, but he wouldn’t admit it,” Cooper said. “Timber would tell my dad, ‘You can’t eat publicity.’ And my dad would say, ‘Oh, you eat that like spaghetti and meatballs.’ He loved the attention.”

The route would take him down Lake Huron, through the Detroit River, and then into Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. From there, he would cross New York primarily via the Mohawk and Hudson rivers. Then on to New York City.

His plan was to leave in mid-June and make it there by Labor Day. When a reporter in Detroit found out about the trip, he asked the bachelor from the Soo, “Are you married?”

Timber Tony’s reply: “Do you think if I was married my wife would let me go on such a crazy trip?”

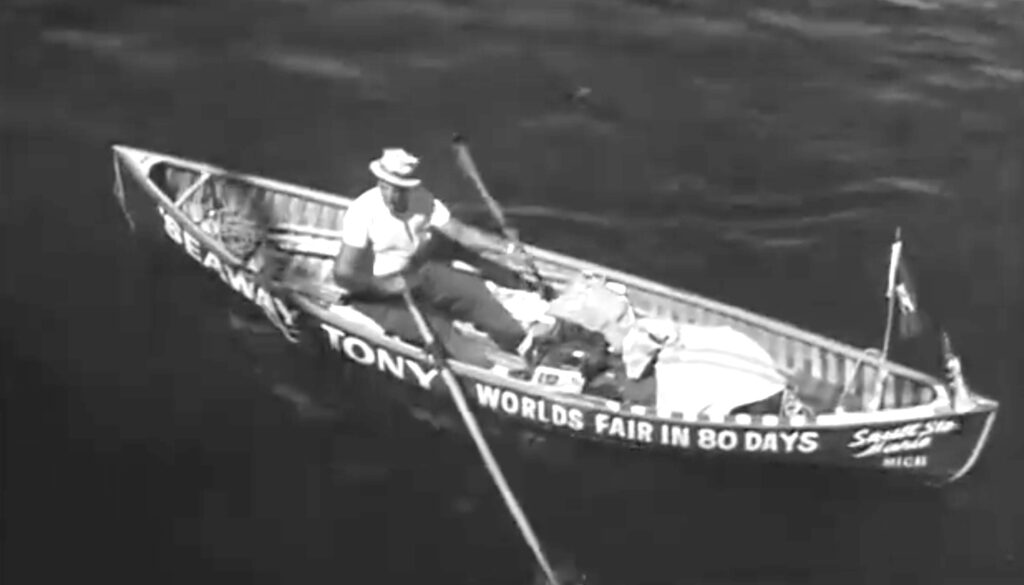

On June 13, 1964, the 45-year-old bachelor put his boat in the water and started rowing. He had no two-way radio or navigation device with him; just some maps. He took a bottle for water and some food. He threw in a blanket and a pillow. He didn’t bring a change of clothes.

His rowboat was basically a modified 12-foot canoe. It had a seat in the middle and no cover or anything to shield him from the elements.

If you’ve ever rowed a boat for a quarter-mile, or even a half-mile, you know how physically and mentally exhausting it is. Taking into account that he’d be missing a few days because of bad weather, he figured he’d have to row about 40 miles a day for two and a half months to make it in time.

He stayed along the shore of Lake Huron and made it to Detroit by July 4. By the time he made it to Detroit, he had become a celebrity. All the local TV stations interviewed him, a group of local dignitaries posed for pictures with him, and they put him up for the night in the posh Sheraton-Cadillac Hotel.

Those were by far the nicest accommodations he’d have for the next few weeks. Most nights, he would just sleep in his rowboat or on the beach. A few times, local folks would put him up in somebody’s house or a motel.

Back in the Soo, Don Cooper and all the other locals were following the trip in the Sault Ste. Marie Evening News. Timber Tony would place a collect call to the newsroom every few days to let them know how the trip was going.

“There was a lot of build-up to it, so we all knew what was going on,” Cooper said. “I was 10 years old at the time, and my dad and everyone else was following the story every day.”

Timber Tony said he would chew tobacco all day and smoke cigars at night, and “never had trouble with short wind in my life.” He would frequently sing to himself as he rowed.

He had some adventures and roadblocks along the way, particularly when he made it to Cleveland on July 17. He called back to the Soo Evening News to let them know he had run out of funds.

“Whether I continue the journey tomorrow depends on one thing—money,” he said. “I’m broke, and unless I get some money, it’ll be a while before I get going.”

When word got back to the Soo that Timber Tony was in trouble, the locals sprung into action. “When he ran out of money, they put canisters up in town in all the restaurants and bars,” Cooper recalled. “Everybody pitched in, and I guess they wired him the money.”

About a month later, when he rowed down the Hudson River into Albany, he presented a letter he had been given by Michigan Gov. George Romney (a big fan of his) to a representative of New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller.

President Lyndon B. Johnson was also following the story.

On Aug. 27, 1964—five days ahead of schedule—he rowed into New York Harbor. Thanks to a nice wind at his back and some favorable tides, he had done it in just 75 days. A huge contingent of media people and boats were on hand to greet him. A newsreel photographer captured every bit of it.

A Yooper Hero

When he got back to the Soo (he took a train home, not a rowboat), Timber Tony was treated like a hero. “They had a big parade for him,” Cooper said. “They put his boat on a trailer and drove it down the main street in town. They gave him a truck that was nicer than the trucks he had.”

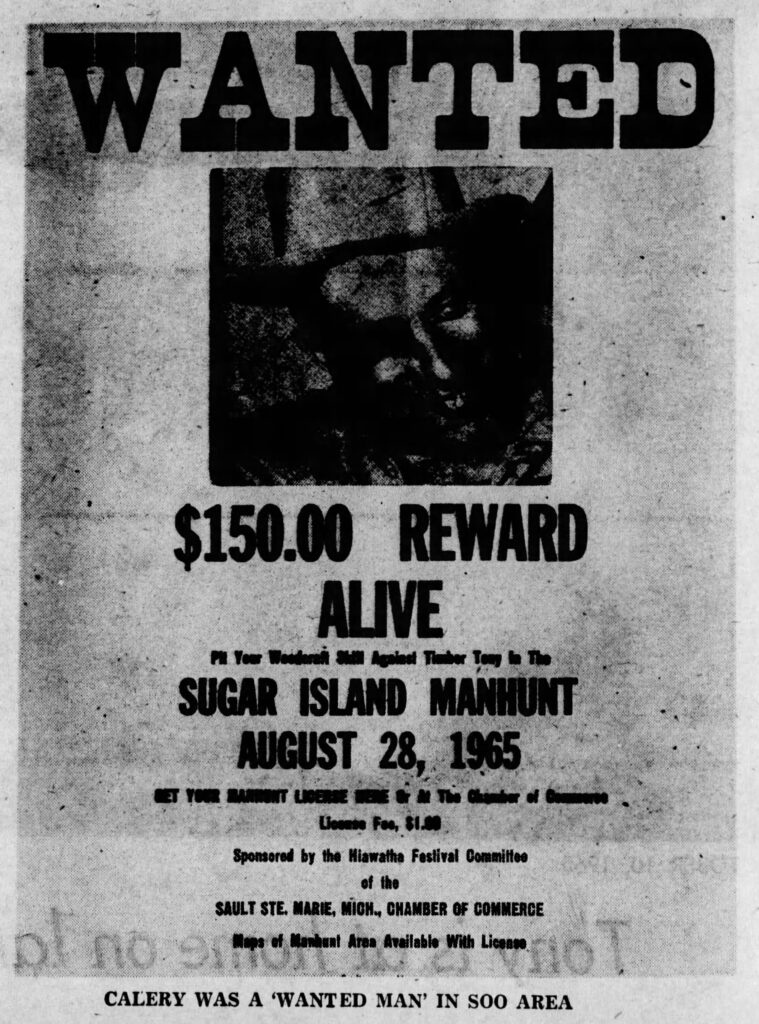

All that rowing had given Timber Tony plenty of time to figure out what his next attention-grabbing scheme would be, and he came up with a doozy: A manhunt on Sugar Island.

Timber Tony got the sponsors of the local Hiawatha Festival to put up $500 for the event. The idea was that hunters would have 48 hours to find Tony on Sugar Island (they just had to touch him, not shoot him). The first one to do it would get $150. If Tony eluded everyone for 48 hours, he’d get $500. The female hunters would get a one-hour head start on the male hunters.

“They’ll never find me on Sugar Island,” he boasted before it started. “I know where to go and where to hide. I know Sugar Island.”

He did know Sugar Island—he had an 80-acre wooded farm there—and the more than 500 people looking for him never found him. “We all said, ‘Timber, you probably stayed in somebody’s cabin.’ He said, ‘No, I hid under a brush pile.’ Yeah, whatever, Timber,” Cooper said.

The 1964 manhunt was so successful that they did it again in 1965, putting up “WANTED” posters all over Sault Ste. Marie to advertise it. Once again, he won the money.

He had a few more tricks up his sleeve in the years that followed. In 1971, and again in 1973, he rowed from the American side of the Soo to the Canadian side… in a bathtub. It took him about an hour. “My brother Roger was in a chase boat that rode next to him the first time he did it,” Cooper said. “Timber couldn’t swim, so Roger was there to fish him out in case he fell in.”

In his late ’60s, he made the 400-mile trip to Muskegon again, just for the hell of it.

In 1993, at the age of 75, Timber Tony’s body finally gave out. But not without a fight.

“I’ll tell you what, I was at the hospital when he was dying,” Cooper said. “The doctor came out and said that Tony’s organs were shutting down. And then the doctor said, ‘His heart just won’t quit. It’s just strong.’ That was Timber.”

It might have been the longest rowboat trip at the time, but Timber Tony’s 2,000-mile journey to New York in 1964 is no longer the record-holder. A few years later, in 1969, an Englishman named John Fairfax became the first person to row a boat solo across the Atlantic Ocean, a trip of about 3,500 miles. His much fancier boat had sleeping quarters.

In 2007, a Turkish man named Erden Eruc began a five-year rowboat journey that took him literally around the world, 41,000 miles in all. Several other people have rowed across the Atlantic or Pacific oceans.

Incredible accomplishments, but all of them are standing on the shoulders of Timber Tony Calery, the legendary lumberjack from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Don Cooper’s son, also named Don, knew Timber Tony as well. He said that indeed, he might have been the most Yooper Yooper of all.

“You think about the toughness and the self-determination that comes along with people from the U.P.,” the younger Cooper said. “Timber Tony was all of that. If you were to line up 10 men from Sault Ste. Marie and say, ‘Pick out the one whose name is Timber Tony,’ you would pick him out 10 times out of 10.”

Buddy Moorehouse teaches documentary filmmaking at Hillsdale College.