Most every city has a nerdy city planner with a masterplan for converting some high-traffic area into a fashionable and eccentric downtown. Waterford is the next to try. The township just received $750,000 in federal grant money—which is to say taxpayer money—to reinvigorate an obscure plot of land, known by almost nobody in Metro Detroit, as “Drayton Plains.” And the township is looking to secure more government largesse.

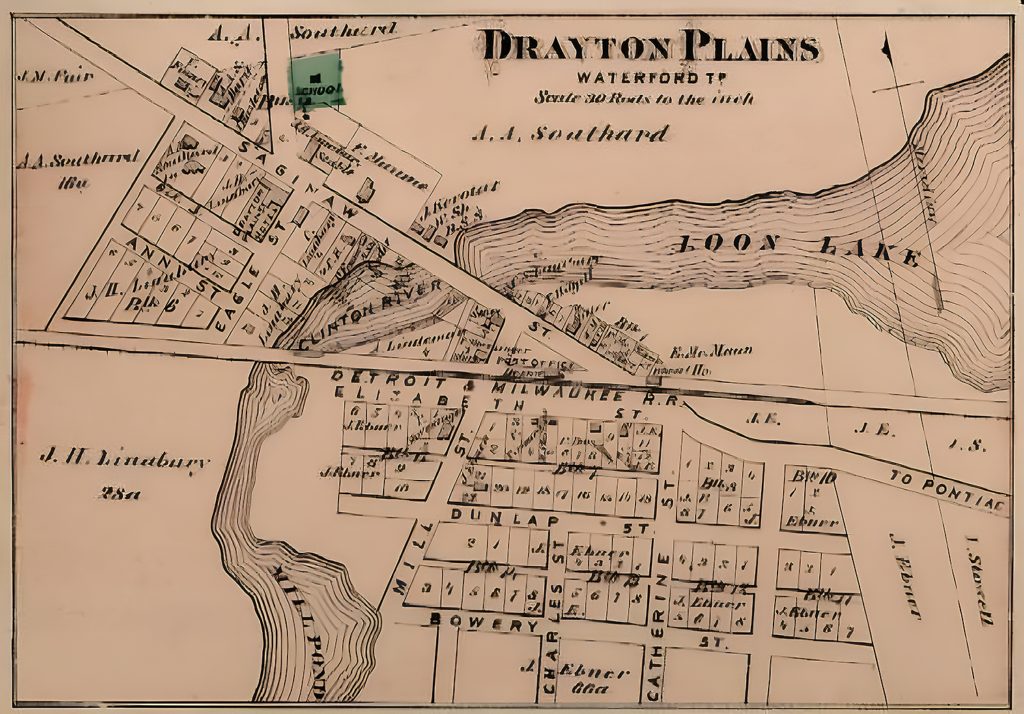

You’ve probably never heard of Drayton Plains, but suburban Metro Detroiters have likely driven through it along Dixie Highway near Loon Lake Rd. It’s a bad area, with a few empty storefronts and abandoned lots nestled into a busy working-class subdivision; but with discretionary spending from the $1.7 trillion money bomb signed into law by President Biden in late 2022, which made FDR’s New Deal look like a fart in a stiff wind, area residents should be able to say, “Now we’re in Waterford” as they drive through.

The drive from Detroit to Waterford is about 40 minutes through the yawning emptiness extending out from Midtown into the western and northwestern reaches of the city. There are also large tracts of unused land, extending northward on Gratiot from Eastern Market. And let’s not forget the empty subdivisions and countless abandoned city blocks in Brightmoor.

These areas are dying for urban renewal. So how does a suburban town like Waterford get taxpayer charity to plan and build a walkable downtown, while the major city next door continues its skid into the gutter? And moreover, how do these initiatives continue to occur with every new state and federal administration?

Former Michigan Gov. Jennifer Granholm came up with the Cool Cities Plan in 2006 to fire taxpayer money at a dozen Michigan cities to splash paint on some facades, remodel some marquees for the theater kids and wine moms, build some welcome centers, and host some live music. This plan was such rousing success and massive economic game-changer for the state that I’d never even heard of it until writing this piece.

So if these plans don’t work, why do they persist? One obvious and very unfortunate reason is the white urban hipsters who’ve gentrified several areas of downtown Detroit into booming walkable economic zones don’t move out to other parts of Detroit when they start families. They aren’t going to force their kids to suffer in Detroit’s public schools. They just pull up and head for the suburbs, usually to Royal Oak, Ferndale, or one of several other Metro Detroit cities that got ahead of the game and began building walkable downtowns. Plymouth, Northville, Milford, and Novi now appeal to affluent Gen Xers.

Fast forward to 2024, and Metro Detroit cities like Waterford—lacking historical downtowns or culturally appeal—are late to the game and trying to catch up.

But government investment often doesn’t work out. Pontiac, located due east of Waterford, has struggled for decades to renew itself through private and public funding to no avail. And it already has what many suburban city planners pine for: A walkable downtown encompassing a restaurant and club district, rows of storefront space, and a hospital in the center of the loop.

Pontiac fell pray to what ails most urban cities, including Detroit. High crime and a steady decline in residents, thus a shrinking tax base, leads to a poor city services. This decline has been so severe that Pontiac no longer is able to fund a police or fire department. Fire and EMS services are now provided by Waterford. In 2013, the already-stretched-thin Oakland County Sheriff’s Office was tasked with policing Pontiac. Who wants to spend a day walking and shopping on streets of downtown Pontiac when there is virtually no police presence and homeless men and women pace the vast abandoned Phoenix Center parking lot?

The policing issue is also a reason Detroit is being left out in the cold. Why would businesses set up shop in a potentially renewed urban development if property crimes are too ubiquitous to guarantee profit? Even cash businesses along Eight Mile, like weed dispensaries, require extraordinary levels of Navy SEAL-level private security because policing is incompetent.

Long story short: Affluent and middle-class urbanites want to live in the suburbs but feel like they’re living in a downtown. Mayors, city councils, and planning managers in Metro Detroit see the potential of economic growth and compete for grants, subsidies, and tax credits to build these walkable areas to compete for residents.

But what do they have for Detroiters stuck inside the crumbling and abandoned city limits? Nothing.

J.Z. Delorean is a writer for Michigan Enjoyer and has been a Metro Detroit-based professional investigator for 22 years. Follow him on X @Stainless31.