Frank “Sugar Chile” Robinson never had a music lesson in his life, but by the time he was 7 years old, he was the most famous boogie-woogie piano player in the country.

Born in Detroit in 1938, Sugar Chile was a child prodigy who toured with Lionel Hampton and Count Basie, performed in a Hollywood movie, and played for President Truman at the White House, all before he turned 8 years old.

He was on magazine covers and in every newspaper in the country. He had a recording contract with Capitol Records, toured North America and Europe, and was making $10,000 a week at his peak. That’s the equivalent of earning $180,000 a week in today’s dollars.

Everybody loved Sugar Chile Robinson.

And then, when he was 17 years old, he gave it all up. Everything. The fame, the fortune, the recording contract, and the touring deals. He quit show business cold turkey so that he could go to college with an eye on maybe becoming a doctor.

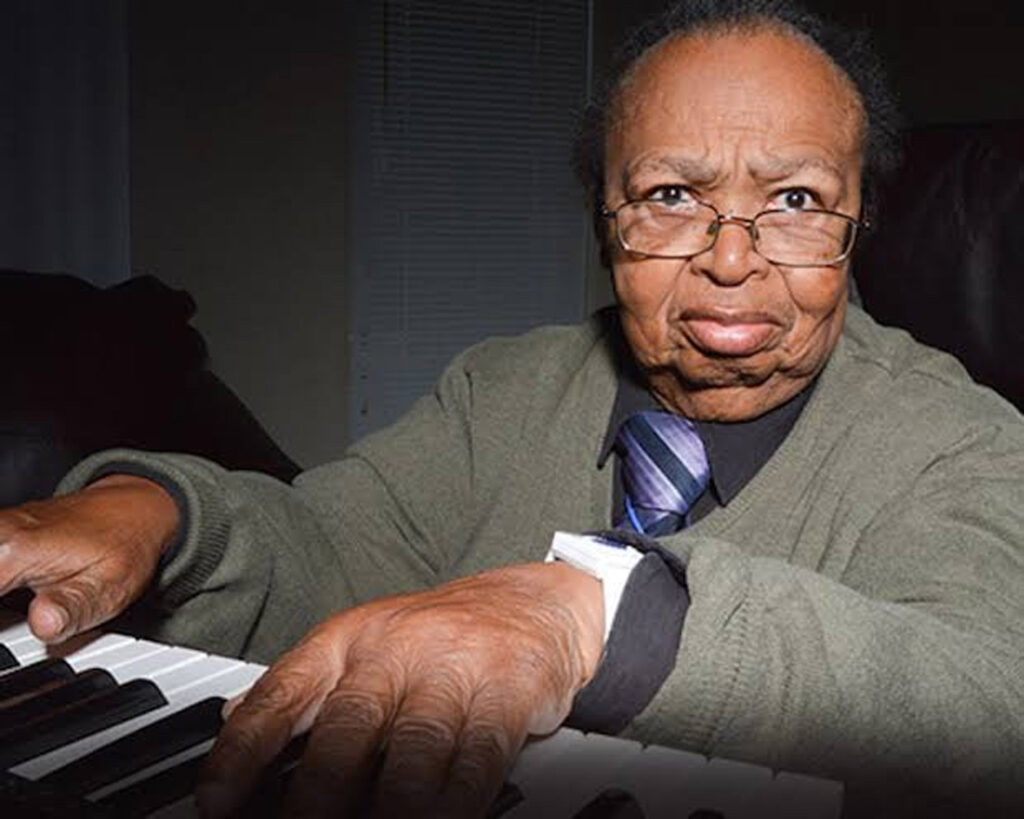

Robinson is still around today, reportedly living with his niece in a modest apartment in Detroit. One of the most famous child musical stars in American history is now an 86-year-old man living an anonymous life in the city he’s called home since the beginning.

Sugar Chile is rarely seen in public anymore (the last sighting of him on social media was in early 2020), and he hasn’t given an interview in decades, but it’s still heartening to know that a genuine musical legend lives among us.

Here’s the story of Michigan’s own Frank “Sugar Chile” Robinson.

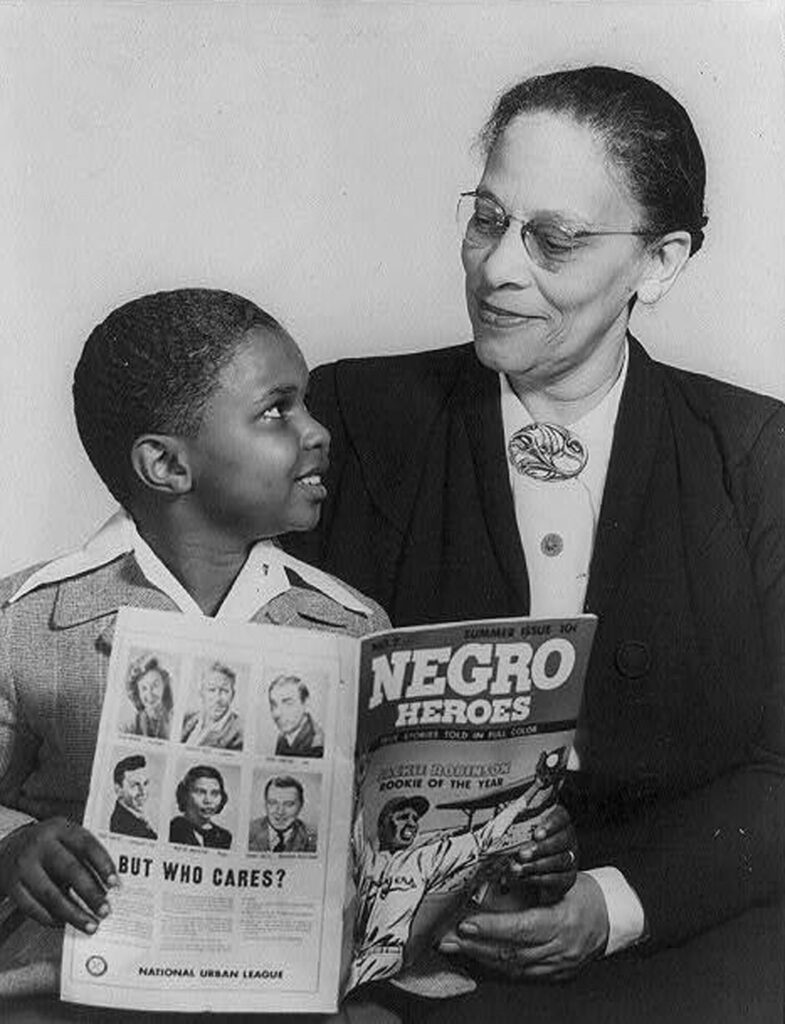

Born on the east side of Detroit, little Frankie Robinson lived in a house on Cameron Street with his parents and six siblings. He was the youngest child and the only one with any musical inclinations, and his mother Elizabeth realized that she could calm down the hyper and precocious toddler by giving him a sugar cube. Thus, he became his mama’s “Sugar Chile.”

The family had a piano, and little Sugar Chile showed his prodigious skills at an early age. He could listen to a song on the family Victrola and then hammer it out on the piano, entirely by ear. His fingers were too small for the keys, so he just banged out the songs with his fists and elbows.

He was amazing, and he also had a booming singing voice that was perfect for the boogie-woogie tunes he was playing and a charming stage presence that melted hearts.

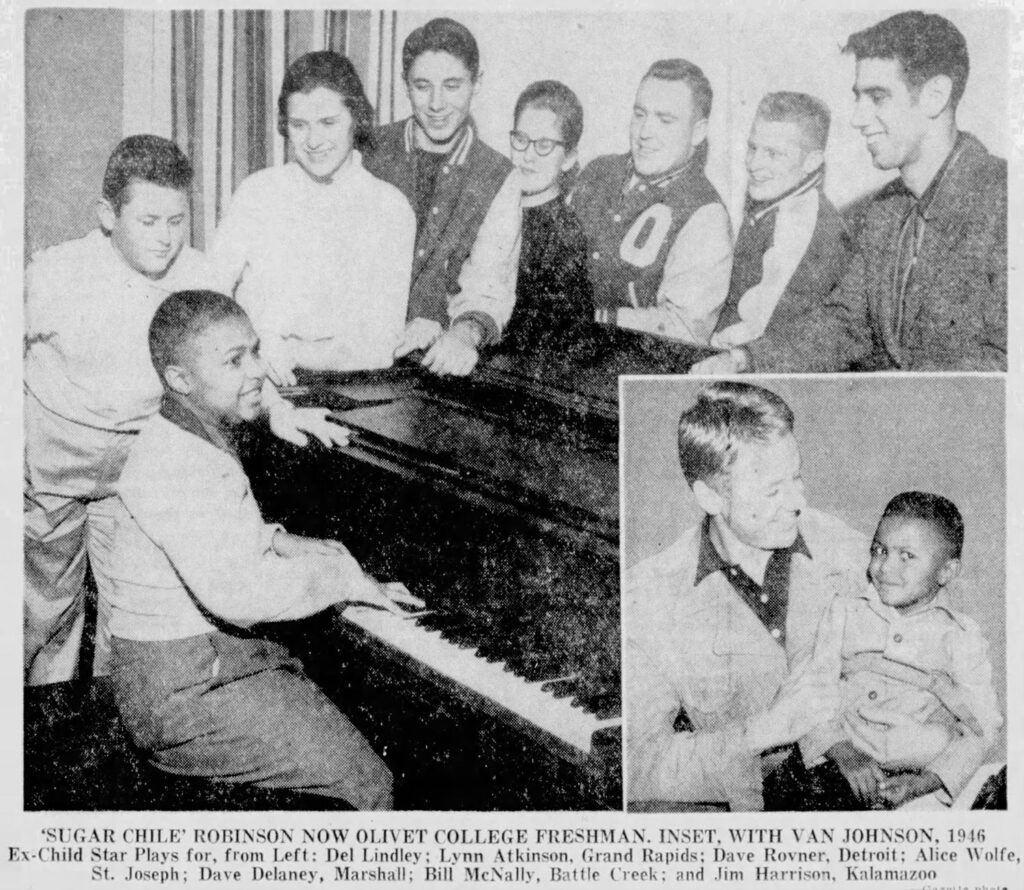

He won a talent contest at Detroit’s Paradise Theatre when he was only 3, competing against mostly teenagers. He started getting gigs at other theaters in Detroit, and the crowds couldn’t get enough of the tiny piano whiz kid. His fame started spreading across the country when he turned 6, as he landed a role in a wartime Hollywood production called “No Leave, No Love,” starring Van Johnson and Keenan Wynn.

Sugar Chile got to perform one of his biggest hits in the movie, “Caldonia,” and he stole the show. He made $250 a week during the Hollywood shoot and met everyone from Gregory Peck to Bob Hope to Lana Turner.

When he got back to Detroit, the Michigan Chronicle did a story on him, reporting: “This little genius, like any other 6-year-old, is now most interested in whether Santa Claus will fill his request for a tricycle.”

On March 4, 1946, 7-year-old Sugar Chile was invited to the White House to perform for President Truman at the first-ever White House Correspondents Dinner. He banged out “Caldonia” for Truman and the hundreds of other guests, and when he was done, Sugar Chile shouted, “How’m I doing, Mr. President?”

“You’re doing alright, Frankie!” Truman responded with a grin.

Sugar Chile’s mom passed away when he was 5, and his dad was always working, so he was mainly being raised by his older sister Dorothy. She would tend to his educational needs and accompany him on road trips across North America and Europe.

When he was 8, Sugar Chile had a huge run at the Texas State Fair in Dallas, setting box-office records while appearing with Tommy Dorsey’s band, Gypsy Rose Lee, and Jackie Gleason. Sugar Chile was the hit of the show.

Even as Sugar Chile grew up, the novelty didn’t wear off. As he turned 10, 11, then 12 years old, he was still packing concert halls around the world. In 1952, when he had just turned 13, he drew a sold-out crowd of 3,000 fans to the Municipal Auditorium in Kansas City. It was about that time, though, that Sugar Chile started letting the world know that music might not be his lifetime career.

An article in the Kansas City Times on Feb. 1, 1952, reported, “Sugar Chile, a veteran of six years of road tours and numerous television engagements, said backstage a musician’s career is fine, but that he wants to be a surgeon.”

Sugar Chile told the reporter that his most prized possession was not his piano but a chemistry set he had back home in Detroit.

Two years later, when he was 15, he made good on the promise. He stopped making records, quit touring, and limited his live performances to just a handful of local shows.

By the time he was 17, he had fully retired. He graduated from Detroit Northern High School and enrolled at Olivet College, a small school in Michigan, where he was pretty much the only black student on campus.

“Sugar Chile is gone,” he said. “I want to come back as Dr. Frank Robinson.”

He never became a doctor, but he did graduate from Olivet College four years later with a degree in psychology. He never did anything with that degree.

Instead, he moved in with his sister and helped manage a party store the family owned at 3906 St. Aubin Street in Detroit.

A reporter from the Detroit Free Press caught up with him in 1969, and Sugar Chile said he had no interest in getting back into music.

“Besides, I’d have to change my style,” he said. “Boogie-woogie won’t do any more. I’d have to switch to jazz or rock.”

Sugar Chile eventually took a job working for WGPR, the first black-owned TV station in Detroit, doing sales and promotions. From time to time, a reporter would track him down and do a “Where Are They Now?” story.

“You want to talk to me?” he said in 1977. “I don’t know about what. Anybody wants to talk to me, they must be crazy. I just don’t want to go back and relive the whole thing. I’m not Sugar Chile Robinson anymore.”

Instead, he spent his time back then working at the TV station and starting a baseball league for kids in Detroit, serving as its commissioner. He lived with his sister and then his niece, never marrying or having any kids himself.

Sugar Chile’s story mostly became lost to history (aside from the jazz fans who remembered him), but he would resurface from time to time, even playing the piano on occasion.

He gave a concert in 2007 in Royal Oak that was captured on video, and it was obvious that he hadn’t lost a step in all those years. Even as recently as 2020, his song “Go, Boy, Go!” was used in a TV commercial for the GMC Acadia.

Sugar Chile’s legacy got another boost in 2016 when President Barack Obama invited him back to Washington, D.C., for the White House Correspondents Dinner—exactly 70 years after he’d performed at the same event for President Harry Truman.

The jazz community came to his aid again in 2017 when word got out that he’d fallen on hard times. A fire had destroyed his valuables, including the bed he was sleeping on. The Music Maker Relief Foundation bought him a new bed and enrolled him in a monthly food program that they paid for.

Sugar Chile has become something of a legend in the Facebook era, as his old videos pop up all the time in a reel or video that somebody has posted. They get hundreds of thousands of views—sometimes millions.

People will see the charismatic little kid whose feet don’t reach the pedals, banging out “Numbers Boogie” or “Caldonia,” and think, “My word, who is that?”

That’s Sugar Chile Robinson. A Michigan legend—then, now, and always.

Buddy Moorehouse teaches documentary filmmaking at Hillsdale College.