Toledo, Michigan — If you look up “Lost Peninsula,” you will see that the address is Toledo, MI 48133. In this tiny Monroe County peninsula live a chosen few who reside in an Ohio city while remaining on Michigan soil.

Since 1915, there has been a 250-acre exclave at the southeastern corner of the state called “Lost Peninsula.” The name dates back to the 1940s when a Detroit newspaperman said Michigan had an Upper Peninsula and a Lower Peninsula and, in the far southeast corner, a Lost Peninsula. Today’s inhabitants have kept the name.

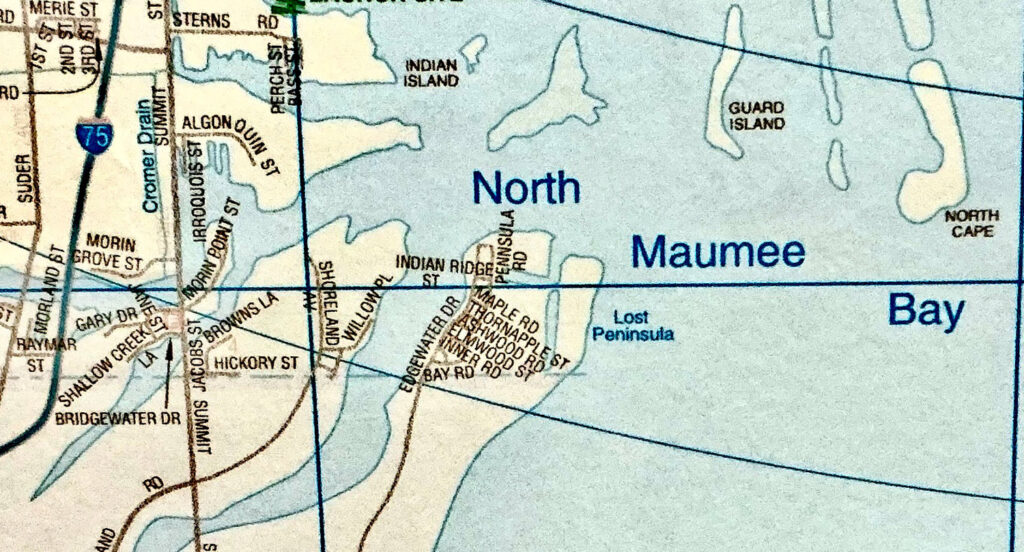

Unless you canoe or swim, you have to drive through Toledo’s Point Place neighborhood to reach it.

Why doesn’t Toledo own this land?

It started with the Toledo War. In 1835 the Michigan Territory and the state of Ohio fought for possession of the Toledo strip, a 468-square mile region spanning from the Indiana border to Lake Erie.

Calling this scuffle a “war” is a misnomer. Only one man was wounded. And it didn’t happen when 22-year-old Michigan Governor Stevens T. Mason led his troops into Ohio for battle. That only led to shots fired over the fleeing heads of the Ohioans. The wounding happened when a buckeye named Two Stickney stabbed Monroe County Sheriff Joseph Wood after resisting arrest in a tavern.

In 1836, President Andrew Jackson stepped in to end the struggle and make Michigan a state. Michigan lost the Toledo strip and Maumee River while gaining the Upper Peninsula. To contain the Maumee within Ohio, the stateline cut through the Ottawa River and over through the top of the eastern peninsula, creating the geographic oddity.

The state line remained contentious for years to come. People fished, trapped, hunted, and farmed on the Lost Peninsula for three decades before it became residential. It wasn’t clear which state owned it until 1915.

The Lost Peninsula gained stronger definition when Michigan Gov. Woodbridge Ferris and Ohio Gov. Frank Willis met to shake hands after a survey that led to the clear delineation of state lines. A stone marker signifying the event was placed at the border. It was a sign people were moving on from the war of 1835.

Nevertheless, this arrangement still created problems.

Toledo provided water and sewer to the peninsula, but power didn’t come until the 1940s when Consumers Power ran a line underwater to reach the exclave. One had to wonder if staying in Michigan was worth all that hassle. Then, in 1960, Toledo proposed to reclaim what Ohio had lost. They were already providing services to the area, after all. If the proposal was successful, the peninsula residents would gain school transportation, snow removal, and trash pickup. In every sense of the word, the proposal was practical.

But the war continued when the majority of the residents signed a petition to stay in Michigan. They wouldn’t give an inch.

Whichever state the land is in, it takes tenacity to live there. On Palm Sunday 1965, a tornado hit the island, decimating Webber’s Waterfront Restaurant and killing two locals. Along with potential for harsher weather, swarms of mayflies descend like an Egyptian plague every summer.

Today, the peninsula has a marina, two waterfront restaurants, and 140 residents who live in about 50 homes. The marina is private, and a gate protects the Ottawa Shores neighborhood from any unwanted vehicles. So even if having this exclave is of no advantage to the state, the people there love it this way. They enjoy the charming size of the neighborhood and a view of the joining mouths of the Maumee and Ottawa rivers that feed into Lake Erie. Life there is serene and private.

If you don’t live there, or have a boat at the marina, there is little reason to visit except to eat at Webber’s.

But even if you aren’t hungry, you can drive down there and see the stone marker that sits in front of the Marina entrance. You can stand with your feet straddling the state line, the entrance of the most coveted and exclusive club in Ohio.

Noah Wing is a contributing writer for Michigan Enjoyer.