Novi — Bosco Farms was a remnant of its glory days. Most local farms had been converted into subdivisions, yet every December, the Bosco family cheerfully draped their larger-than-life Christmas wreath on the towering red barn, which sat behind their immaculate white manor house, for passersby to enjoy.

A few years back, the farm was razed, with the barn stripped for parts and the mansion demolished to build a splash park next to some soccer fields.

The pile of white rubble hit a nerve and awoke me to a disappearing old rural town that had long succumbed to the suburban blob.

Rural life is easygoing but intimate, where people live near nature and gather on Main Street. Urban life is intense but impersonal, offering excitement and wealth for the mobile and ambitious. Suburbia fuses both in spacious homes and accessible commerce. It’s always expanding outward.

A good city channels growth by conserving its buildings and culture to give newcomers something to join. But without forethought and planning, siloed neighborhoods allow people to live like next-door strangers.

Sadly, that description fits my hometown. How did Novi end up like this?

Today, a progressive-tilting, slowly growing, expensive town, Novi’s most popular qualities are its shopping, good schools, safe streets, and efficient city services.

Though a well-to-do family can access anything in shops, restaurants, gyms, and amusements, its weakened civic life meant that growing up in this town, something always felt off. With its sections tied together by roads and parking lots, Novi lacks a real cultural presence.

This was not always so. A rich civic life requires people with a shared identity to physically gather together. The old Novi had that.

For 150 years, it was a tight-knit township where people obsessed over their history, raced horses, and shot turkeys, with life centering around Novi Corners—where Novi Road crosses Grand River Avenue—for business and civics.

But when the open fields and riding stables became sprawling neighborhoods filled with upper-class professionals, their kids outpaced school buildings. City planners needed new sites both for burgeoning schools and municipal offices.

This period, the few years after Novi became a city in 1968, was a brief window of opportunity to build a physical heart to the city.

But rather than build new sites on Novi Road and near Novi Corners, as tradition would have guided, planners relocated the library, police department, and city hall to 10 Mile Road in lopsided modernist buildings on donated farmland.

The decision made financial sense but uprooted the government from the economic center, with lasting consequences.

Every decade, the city developed new business centers as pseudo-downtowns, like limbs without a body: Twelve Oaks Mall (1977), Novi Town Center (1987), Main Street (1995), and Fountain Walk (2001).

Even the New York Times called Novi “a suburban Oz” in 1987. The former “blip on the Michigan map” with its oak trees and apple farms had “become a monument to suburban boom and excess.”

Carol Mason, a resident who sold real estate to newcomers, told the reporter that when she first arrived in Novi, she would have cows grazing in her backyard, requiring her to call the farmer to retrieve them.

“It’s a dream world. I should have taken pictures,” Mason said about Novi’s pastoral beginnings.

In that world, everybody knew everybody. “All dispatchers had to do was give me a name,” said Novi’s police captain. “I didn’t need an address.” Neighborly disputes were solved with a talk over coffee and homemade bread.

Once incorporated, citizens never voted to halt development. Development was unavoidable, and the city failed to do it well. Being too spread out to naturally densify like other cities, Novi jumpstarted its growth when postwar sprawl and design held sway.

I came of age as that new world was showing its age. The mall declined with online retail; the Main Street center had chronically underfilled buildings.

Once as a teenager, I explored these buildings, walking through vacant office after vacant office, only to run into an old elementary school friend doing the same. He bragged: “I do this all the time.”

As it was difficult to bike beyond our subdivision, my sister and I often explored the nearby woods, fields, and wetlands—many of which have been bulldozed for new neighborhoods.

Even as places in Novi seemed disconnected, suburbia never ceases to encroach.

Hints of its once-vibrant past remain in odd corners of the old town. Stuart’s, an old ice cream shop, has barely changed; another is Guernsey’s, which has the best ice cream in the region.

The Walled Lake Pavillion still hosts festivals and picnics. The Old Rogers home is now a Japanese restaurant where reported hauntings have become the stuff of urban legend.

And the old Tollgate Farm is an MSU research center. The old Methodist Church is still in use, while our city’s claim to fame—the record-breaking Novi Special race car—is displayed in the Civic Center.

Even the audacity of Twelve Oaks Mall garners nostalgia with time.

Novi needs to integrate businesses within neighborhoods, build denser but beautiful places, make streets walkable and not merely drivable—and over time tether the city together. Some recent commercial and housing developments are aiming for that.

Couples go to the suburbs to start families, and post-Zoom, white-collar work depends less on daily trips to the city; trade crafts are needed everywhere; and manufacturing is spreading to unexpected places.

Novi is still well-positioned to take advantage, but the city layout is tough to overcome.

Growing up, my family frequently spent time in a small town near Lake Missaukee.

In Novi, life was centrifugal and cookie-cutter. Freedom was found in a car. In Lake City, we could bike anywhere around town, without cell phones, needing only a friend and an imagination. Lake City was a rooted flesh-and-blood town with common places that enabled a common culture.

That is why my parents had us spend the summers there: It was freeing. The small town’s physicality gave us the childhood formation once common to earlier generations but fleeting in suburbia.

Novi’s past mistakes need not spoil our hometown. Planners scattered the parts and obscured the whole, but the spirit that built them has not been excised.

Pioneers settled Michigan swamp for agricultural endeavors like Bosco Farms. Today we could tame the suburbs for another form of communal life.

That takes patience and a public spiritedness in local politics and business development, but if we plough ahead, Novi’s glory days are yet to come.

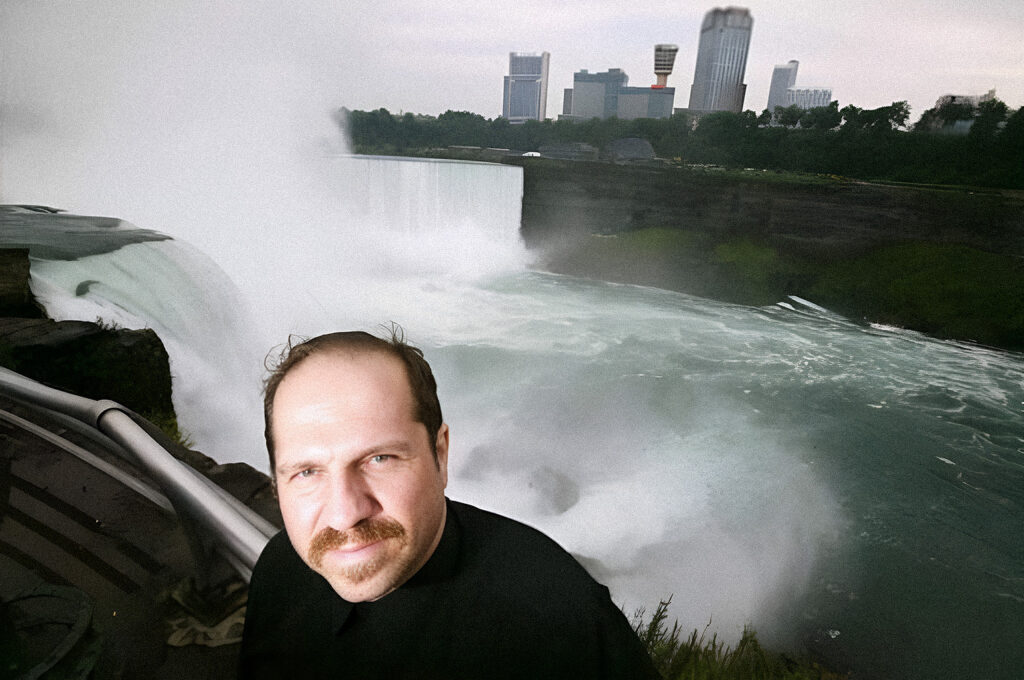

Ryan Shinkel is an editor with Athwart, an intellectual web magazine. Follow him on X (@ryanshinkel) and Substack.