If you passed through the town of Mears on a summer’s day in 1940, you might have come across a roundish man trudging along in green pants, a blue shirt, a bright red tie, and a Derby hat. He may have taken a ride from you if you’d offered. Or, perhaps stopped to talk and glean your latest gossip.

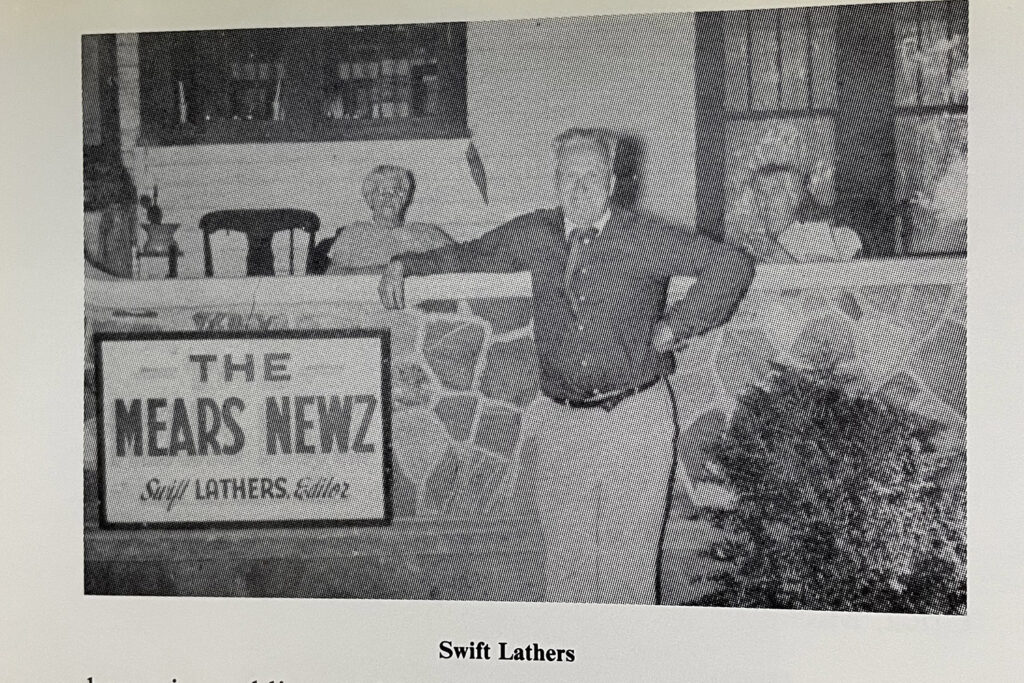

The man was Swift Lathers: school teacher, lover of nature, father of six, and “editor, printer, and bottle washer” of The Mears Newz, the “smallest newspaper in the world.”

Born in Detroit in 1889, Swift was just 20 when he got off the train at Mears, eager to teach youngsters in a one-room school house. He’d completed high school at 16 and college at 19. He studied law but never took the bar. Teaching was his vocation, but his real dream was to start his own newspaper. Mears would be just the place.

It takes about four seconds to drive through Mears today. It didn’t take much longer then. Located halfway up the Lake Michigan shoreline, just five miles inland, the town is a country man’s dream—surrounded by farmland, rolling hills, deep forests, and vast stretches of sand dune to the west. Swift loved it all.

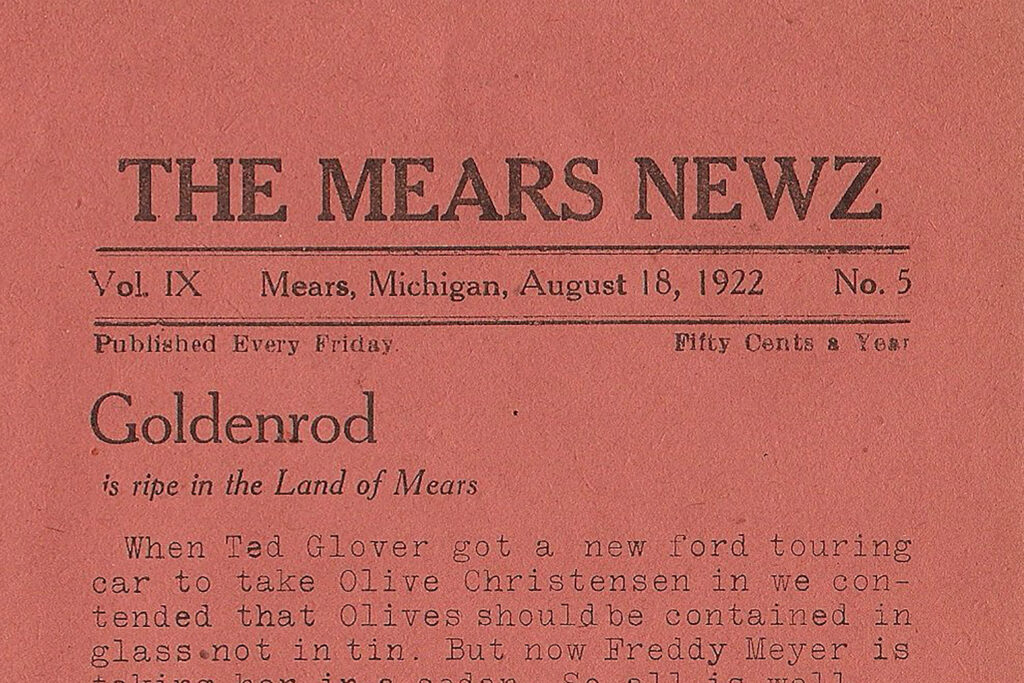

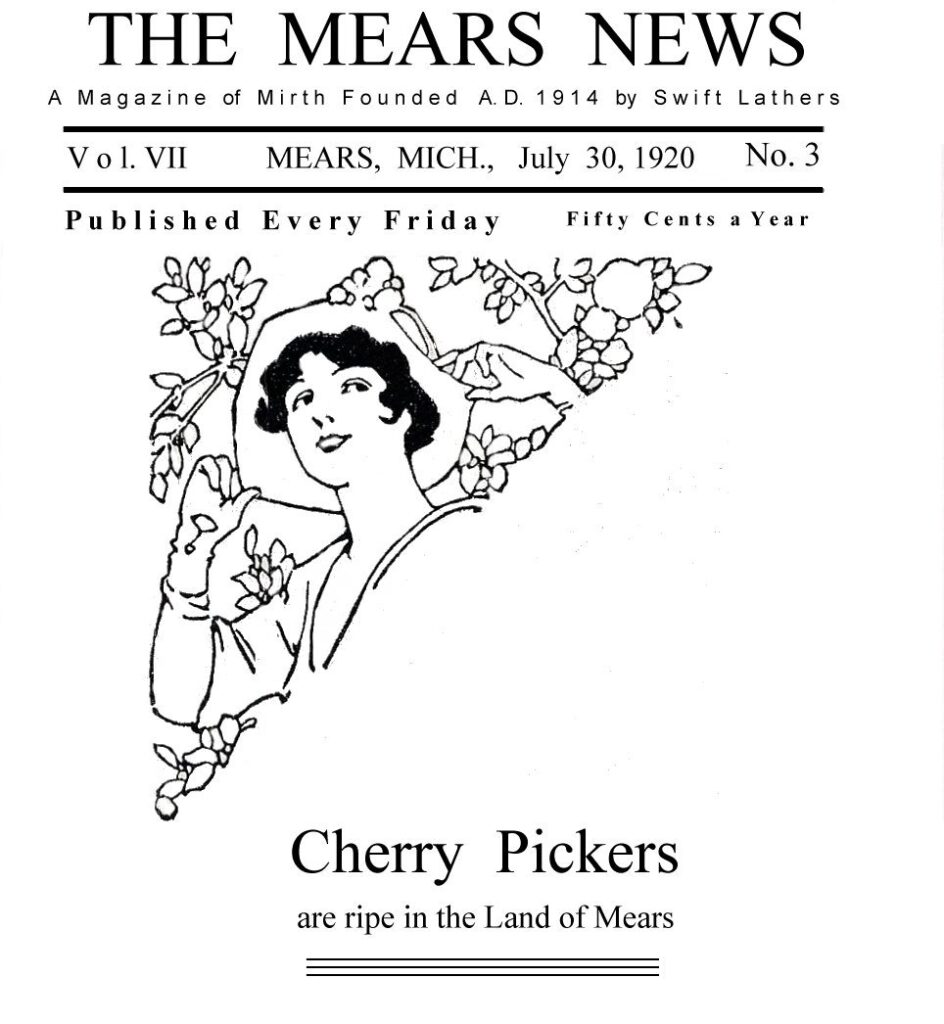

As his paper got going, “[Such-and-Such] Is Ripe in the Land of Mears” was the title headline to every issue. “Parsnips Are Ripe in the Land of Mears.” “Kite Strings Are Ripe in the Land of Mears.” Porch Gliders, Relish Recipes, Blue Pencils, Irish Stews—all ripe in the land of Mears.

Measuring 5-by-7 inches and just four pages long, each Mears Newz issue was written, edited, hand-addressed, and delivered by Swift himself. The paper ran continuously from 1914 to 1970, all the while championing the working man, the little man. Swift was a staunch defender of the free press, an endless supporter of local schools, families, community, and faith.

“The Mears Newz will be devoted to the needs of Golden Township, and the best interest of Ourtown, otherwise known as Mears. The newspaper will do its part for Our Little Town,” ran the very first issue in 1914.

From the outset, Swift decided a year’s subscription would be 50 cents. When a local offered just a quarter, jesting the paper wouldn’t last more than six months, Swift famously changed that rate. From then on, it would be 50 cents for a year, $1 for six months, and $2 for three months.

Those prices never changed. According to his children, Swift was uninterested in money and possessions anyway. He never owned a phone, nor a car, and used a manual typewriter instead of electric. For years, he printed the paper himself on a foot press, having his children fold each issue by hand.

Locals relied on The Mears Newz, and soon subscriptions grew, eventually branching out of rural Michigan to homes across the U.S. When the number of subscribers got a bit too numerous to handle, however, Swift solved the problem by taking a pair of scissors to the subscriber list. All names beginning with A, B, or C got the ax, as did everyone after S.

Swift was a romantic at heart. Among his other wild endeavors was the homesteading of a new town on the Silver Lake dunes, a place that would one day become part of Silver Lake State Park.

Dubbed Dune Forest Village, it comprised a few homes, a church, a schoolhouse, and even a general store and restaurant. He worked on it from 1939 to 1957, carrying half the building materials up the dunes himself. He envisioned an “island” getaway for his family and others.

Nature had other plans. Some of the structures remain to this day, but they’ve been covered with decades of shifting sands. Vandals and the eventual state park took the rest.

Still, Swift was passionate about his project and penned several books about the village, all while continuously publishing his weekly paper. The Mears Newz ran uninterrupted for 56 years, each issue starting with a longish editorial on the gist of local goings-on. The rest featured chatter about who visited who and when, lost dogs and broken arms, out-of-town visitors, and funny asides from Swift’s perspective:

– 1937: “Kathryn Doub gave a lot of kids in her English class an E. She better watch out or she will have them all to teach over again next year.”

– 1956: “Pearl Hunter likes horseradish on toast. She also likes the flavor in her salads.”

– 1961: “Sometimes when I go out of Freeman Wheeler’s house I forget the doorknob doesn’t turn. It just needs to be squeezed from the right side and then the door will be opened.”

Unfortunately, not everyone was happy with how they were portrayed in The Mears Newz. Several times, Swift was taken to court. Always acting as his own attorney, he usually won, including once when a case made it to the Michigan Supreme Court.

When someone didn’t have time for legal business, they’d take up a matter with Swift right there on the street. He had a few missing teeth as a result.

The final issue of The Mears Newz was printed in 1970. Swift was delivering it at the time of his death from a heart attack. He was buried with it tucked beneath his arm.

These days, worthy local newspapers are few and far between. Most either folded completely starting in the 1990s or were bought up by huge corporations, becoming shells of their former selves. This has left many rural “news deserts” where locals can’t get the news they care about.

It isn’t easy being a local reporter, of course. Anyone who’s written about the community they also live in has inevitably bumped into an unhappy reader or two at the grocery store or library.

But when news only comes from national or state-wide sources, small towns like Mears suffer. Information is sparse, connections break, and community is lost. Even in the early 20th century, Swift understood this.

It wasn’t fame or fortune he sought. It was an outlet for the love and respect he had for his country community—a place few outsiders had ever heard of. Even amid the court cases and probably many-an-evil stare in church, Swift continued reporting on the news that mattered to his neighbors and friends.

He was a dreamer and a poet of the highest quality, and despite his small-sized paper, the impressions he left are grand. Just as Swift never stopped writing, it is doubtful we will ever stop writing about him.

Faye Root is a writer and a homeschooling mother based in Northern Michigan. Follow her on X @littlebayschool.