Before he started posting about Naziism, before his divorce from Kim Kardashian, and even before his Sunday Service gospel era, Kanye West just wanted to sell more $220 sneakers.

Ever the marketing genius, Kanye West decided that buying the front pages of the country’s major print newspapers for a day would earn headlines the world over. And he was right.

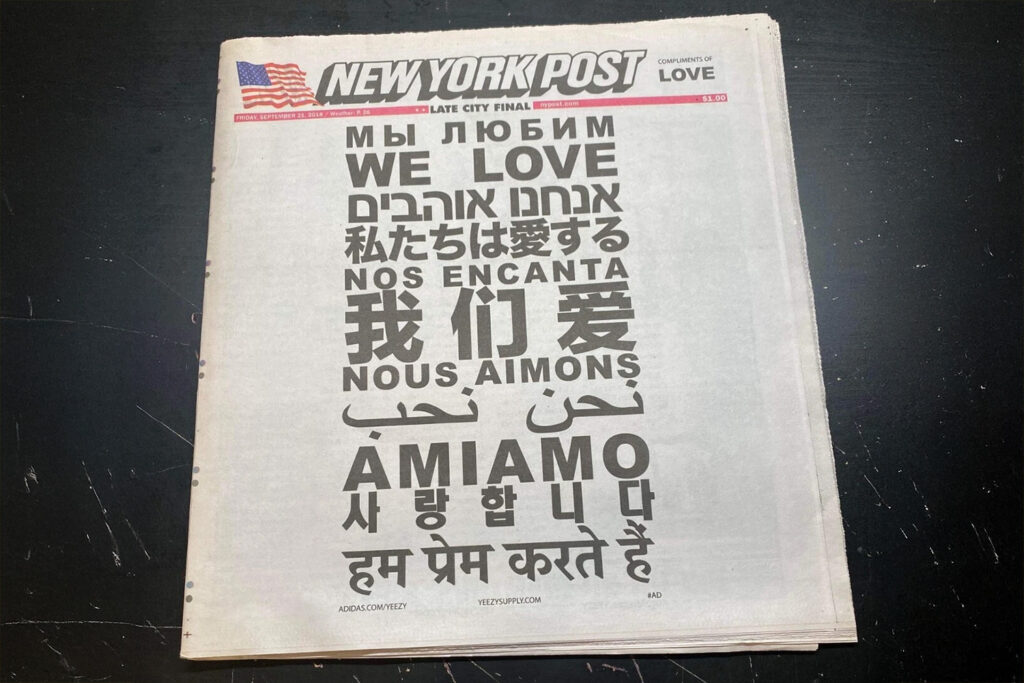

On September 21, 2018, Kanye placed what might be the biggest print ad buy of all time. That day’s issues of the Detroit News, Detroit Free Press, Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Chronicle, Miami Herald, New York Post, and Los Angeles Times were wrapped in four pages of extra newsprint, obscuring the news of the day.

The last time a Detroit paper had done anything similar was two years before, when the Detroit Free Press ran a full-cover ad for the Chevy Silverado. But this wasn’t just an ad placement from a local flagship business, it was a cynical stunt.

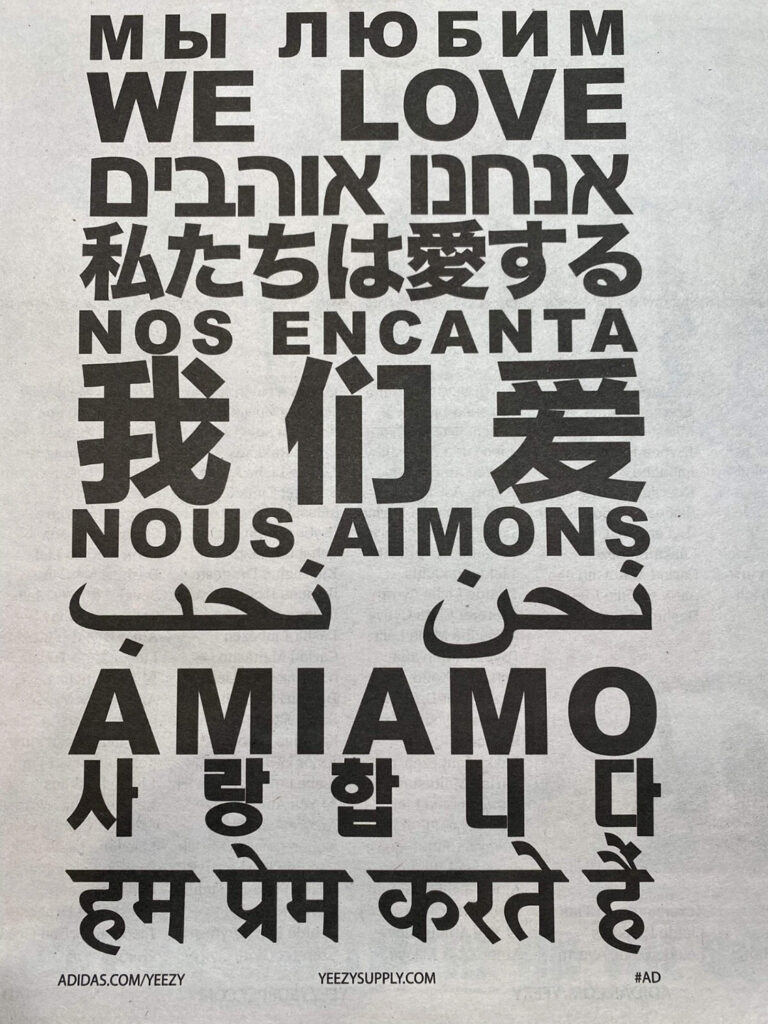

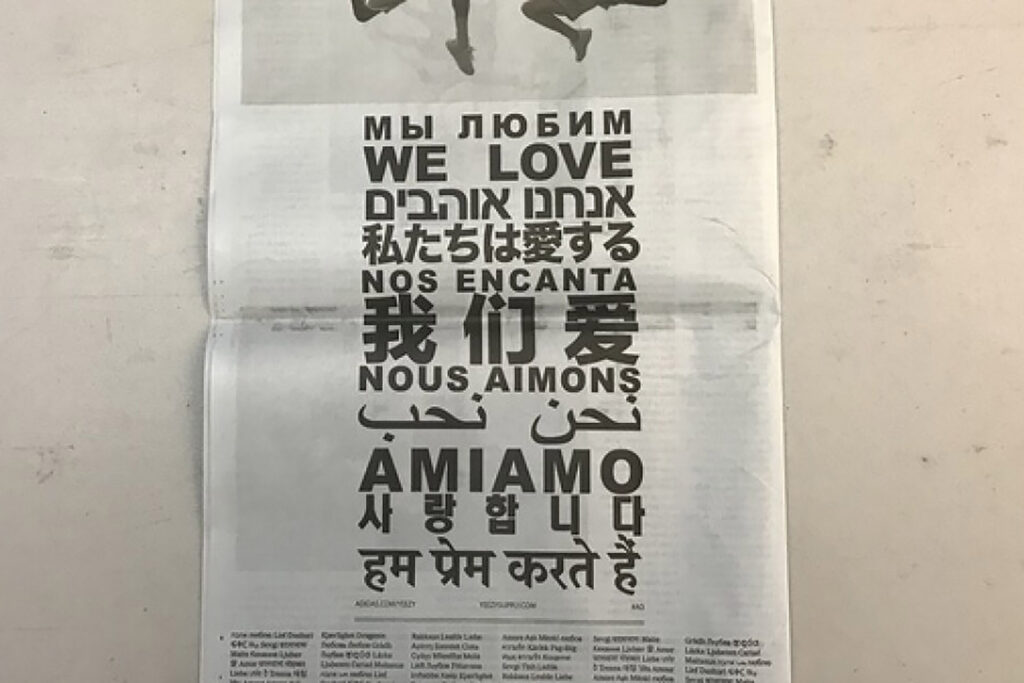

The wrapper featured the words “We Love” in 11 different languages, with photos of flexible young people wearing the “Triple White” Yeezy Boost 350 V2. The interior sheets had more of the same, with more photos and smaller characters in various arrangements randomly everywhere.

I had been editing opinions at the Detroit News for a few months when the issue ran. When I got to the office that day, I was stunned by what the ad sales team had done.

What did it say about journalism that a California rapper could make himself front-page news, and that the ad sales team wasn’t worried about subscriber revolt? Did the name printed on the wall in the entry way mean anything, or was the whole newspaper worth as much as the rusting newspaper boxes scattered around town?

I didn’t have answers then, but seven years on, I think Kanye’s ad buy damaged a traditional media still reeling from Trump’s election. Kanye literally covered a product meant to be read by just about anyone with characters people couldn’t read. He inverted the idea of a newspaper for a day.

That was the shock of it. Something meant to convey as much information as possible about our city wasn’t comprehensible at all. You had to stare, wonder at the audacity of it, and shake your head at the executives who didn’t think this would cause reputational damage.

The Detroit Free Press admitted that the ad could have cost “upwards of $100,000.”

So with a marketing budget of about $700,000, the rapper embarrassed many of the metro newspapers that matter. As a zealous rookie journalist, I assumed it would’ve taken more. I hoped it would’ve.

With the pivot away from digital ads and classifieds to paywalls and digital subscriptions, these newspapers may have reached some sort of terminal falling velocity. They’ll be around in some form for a long time, with reporters mining X for the day’s news and publishers starting each morning praying that subscribers don’t look too hard at their credit-card statements.

If I learned one thing that September day, it was just how easy the establishment media could be bought, and how reluctant they were to admit that it had happened.

Mark Naida is editor of Michigan Enjoyer.