The sea lamprey is a horrible creature: an eel-like, parasitic fish that vacuums itself onto other fish and uses its concentric rows of teeth to suck the life out of them. It serves no purpose in the Great Lakes other than to kill better fish.

An invasive species, sea lampreys were well on their way to destroying the Great Lakes in the 1940s and 1950s by killing all our game fish. Until a New York transplant by the name of Vernon C. Applegate destroyed them.

It took him a few years, but eventually, he won. Or mostly won. Sea lampreys are still an ongoing issue in the Great Lakes, but they’re largely under control thanks to the dogged work of Dr. Applegate. And the story of how he figured out how to kill them reads like a true-crime novel.

The tale begins in the early 1800s, when sea lampreys were causing a bit of damage but were mostly confined to their natural habitat in the Atlantic Ocean. Biologists started spotting a few of them in Lake Ontario in the 1820s, but Niagara Falls, which separates Lake Ontario from Lake Erie, was keeping them out.

All that changed starting in 1919, when Ontario’s Welland Canal was expanded to allow shipping travel through the St. Lawrence Seaway. The canal opened up the Great Lakes to shipping, and it also allowed the sea lamprey to start moving upstream into the other lakes.

By 1921, sea lampreys were spotted in Lake Erie. Then they were found in Lake St. Clair in 1934, Lake Michigan in 1936, Lake Huron in 1937, and finally Lake Superior in 1939.

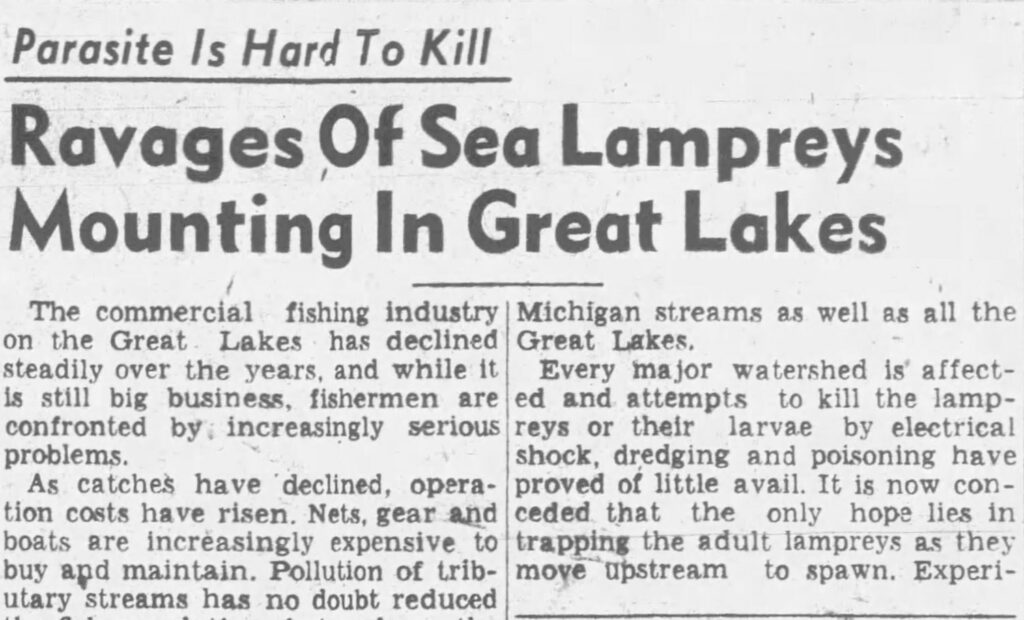

They were devastating the fishing industry. Before the sea lampreys arrived, fishermen were taking in about 15 million pounds of lake trout in the upper Great Lakes every year. By the early 1960s, that was down to about 300,000 pounds. In Lake Huron alone, the catch dropped from 3.4 million pounds in 1937 to almost nothing a decade later.

A single sea lamprey can kill 40 pounds of fish in its lifetime, and only about 1 in 7 fish attacked by a lamprey will survive.

In the 1940s, the parasitic devils were well on their way to taking over all the Great Lakes. The commercial fishing industry would be decimated, recreational fishing would be eliminated, and the economic damage to Michigan would have been immense. The sea lampreys were making their way into Michigan’s streams as well, so our state’s smaller lakes were also on the verge of losing all their fish.

Then a hero emerged.

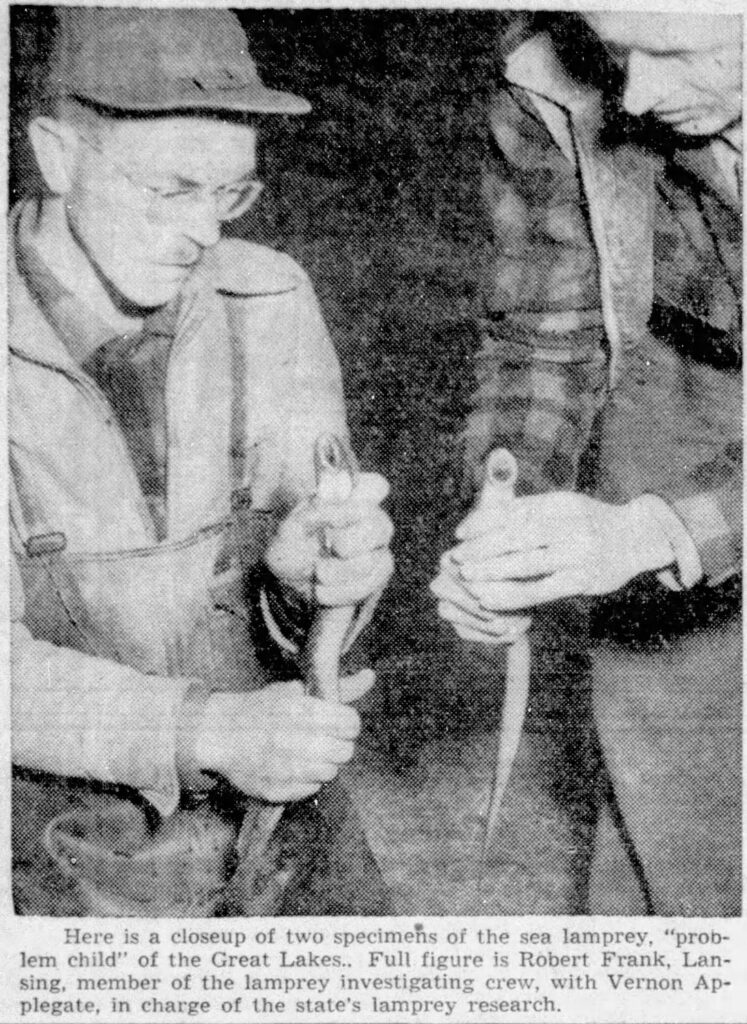

Vernon C. Applegate grew up in New York and had a Queens accent as thick as mud. He came to Michigan in the early 1940s to enroll in the graduate biology program at the University of Michigan. When he heard about this parasitic creature that was starting to invade, he decided to make it his focus of study as he finished up his doctorate.

U-M’s Institute of Fisheries Research put Applegate in charge of its sea lamprey research and gave him a simple charge: Find a way to kill them.

“We are making an inventory of spawning streams this spring to see where the sea lampreys are spawning and how they have multiplied and spread,” Applegate told the press in 1947.

Applegate decided to set up his base of operations at an old Civilian Conservation Corps camp on the shores of Ocqueoc Lake, just west of Rogers City. The streams in the area had a lot of sea lampreys spawning, so it was the perfect place for the laboratory. Applegate put together a crew of lamprey killers that included Lansing’s Robert Frank and West Branch’s Floyd Simonis.

After studying their migration habits and gaining detailed information on their genetic makeup, Applegate’s crew started attacking the sea lampreys in a variety of ways. They tried introducing the American eel into Michigan’s streams and trapping lampreys in the streams before they got to the Great Lakes. Nothing was working.

Applegate was relentless, though, and after a couple years of dead ends, he and his team decided on a new course of action. They needed to find a chemical poison that would kill the sea lampreys but leave the other fish alive.

This was a painstaking process. They would take a chemical compound and then mix it in a bag of water with two sea lampreys and two trout to see if it would kill the lampreys but not the trout. They tried hundreds of different combinations. Then thousands.

Finally in 1956—a full eight years after he had started the kill-the-lampreys project —Applegate found the right combination. The process took three years, cost $1.25 million, and 5,000 different chemicals from 65 different companies.

Applegate and his team finally tried a poisonous chemical compound from Germany called “3-trifluoromethyl-4-nitrophenol,” and it worked. They mixed it in the bag, and it killed the lampreys but not the trout.

Eureka!

Applegate summoned the press to his office in Rogers City and told them they finally had a breakthrough. He told them it might still take years to get the sea lamprey problem under control, but they had found the formula.

“If the poisons succeed, it would take several years to treat all the streams where lampreys spawn.” Applegate said. “I suppose restocking of lake trout could begin before the rivers are cleared, but the process of bringing back fish will be long drawn.”

By this point, Applegate was heading up sea lamprey efforts for a new group called the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, made up of the states that border the Great Lakes and Canada.

Once they found the magic potion that would kill the beasts, the commission decided to start with Lake Superior and then move on to Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. They started treating the waterways, and the sea lampreys started to die.

In 1958, a front-page headline in the Petoskey News-Review declared victory: “Sea lamprey is defeated in Great Lakes.” In the story, Applegate said, “Our selective poisons have been unconditionally successful.”

Applegate had saved the Great Lakes.

There are some who say there should be a statue of Applegate somewhere along the Great Lakes, but after he did his heroic work in the 1940s and 1950s, he was largely forgotten. He lived the rest of his life in Rogers City, and when he passed away in 1980 at age 61, not a single newspaper in Michigan reported the news.

His legacy got a boost in 2007, though, when the Great Lakes Fishery Commission decided to give an annual honor called the “Vernon Applegate Award for Outstanding Contributions to Sea Lamprey Control.” The award is given annually to an individual or group who furthers the cause of sea lamprey control.

Sea lampreys continue to cause problems in the Great Lakes and the battle against them continues every day. Thanks to the efforts of Vernon C. Applegate more than a half-century ago, though, the problem isn’t nearly what it was. Before Applegate came along, sea lampreys were killing more than 100 million pounds of Great Lakes fish every year. Now they kill less than 10 million. Just this past November, the Great Lakes Fishery Commission declared that the trout population in Lake Superior has been “fully restored.”

The man deserves a statue, and Rogers City, where he lived and worked, would be a great location.

Buddy Moorehouse teaches documentary filmmaking at Hillsdale College.