No one knew Dr. Jack Kevorkian when he started making calls to local media in October 1989.

Come to my press conference, he said. I want to show you my new device. It kills people.

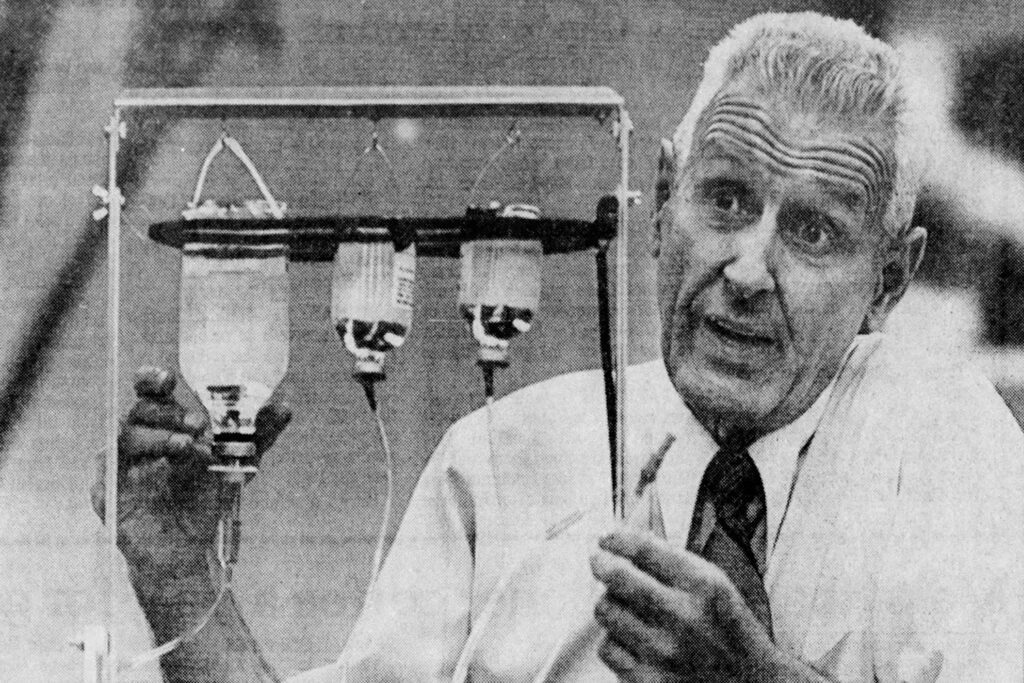

The device was a “suicide machine,” something the Michigan pathologist put together using $30 worth of scrap parts he found at garage sales and hardware stores, that would allow sick or suffering people to kill themselves by pushing a button. The machine would help a person inject a series of fatal drugs that would quickly induce a coma and then death.

Not surprisingly, the media showed up in droves to see the sort of crude IV tower with three tubes containing the drugs. Kevorkian was all smiles when he explained why he built it.

“It’s dignified, humane, and painless, and the patient can do it in their own home at any time they want,” the 61-year-old Kevorkian said. “I’m here to help anyone who’s in distress, or thinks he is. I couldn’t let dogs suffer like that. How can I let a human?”

The critics—including most medical officials, police, and prosecutors—were appalled. “It’s no different whether you give the patient a gun or a knife,” said Dr. Myron LeBan, president of the Oakland County Medical Society.

Kevorkian took great pains to point out that he wouldn’t be doing the killing. He’d just be hooking the condemned person up. The patients would be killing themselves.

From the beginning, Kevorkian thirsted for fame and publicity. He didn’t just want to help people kill themselves in peace and quiet. He wanted to call attention to the cause and to himself. The newsmen were happy to oblige.

Less than a year after his all-smiles press conference, Michigan’s infamous new “Dr. Death” racked up his first fatality.

Janet Adkins, a 54-year-old Oregon woman with Alzheimer’s disease, came to Kevorkian seeking help to take her own life, and he was happy to oblige. On June 4, 1990, he set the suicide machine up in his 1968 Volkswagen van and then parked it at the Groveland Oaks Park near Holly, while Janet pushed the button. About three minutes later, she was dead.

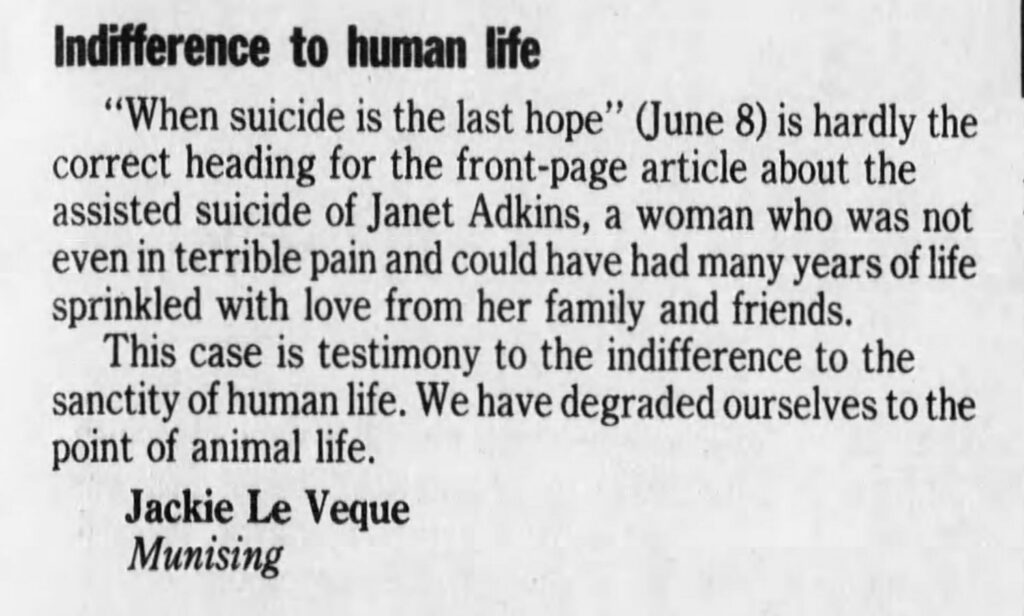

When word got out, it started a firestorm of controversy and debate that has continued ever since. On June 15, 1990, the Detroit Free Press printed a full page of letters to the editor about Kevorkian that were an equal mix of people applauding and condemning him.

“Hats off to Dr. Jack Kevorkian and his wonderful machine,” wrote E.P. Michalke of Emmett. “I hope that he will never again have to sneak around to end human suffering.”

Jackie Le Veque of Munising disagreed: “This case is a testimony to the indifference to the sanctity of human life. We have degraded ourselves to the point of animal life.”

Many also pointed out that Adkins was not terminally ill. She could have lived another 10 or 20 years. Medical professionals said that Kevorkian violated the Hippocratic oath (“First, do no harm”). He wasn’t helping save lives; he was helping take lives.

Public opinion aside, the assisted-suicide death of Janet Adkins brought Kevorkian his first murder charge and made this one of the biggest stories nationally in the early 1990s. And when the flamboyant doctor went looking for a flamboyant lawyer, he found one in Geoffrey Fieger.

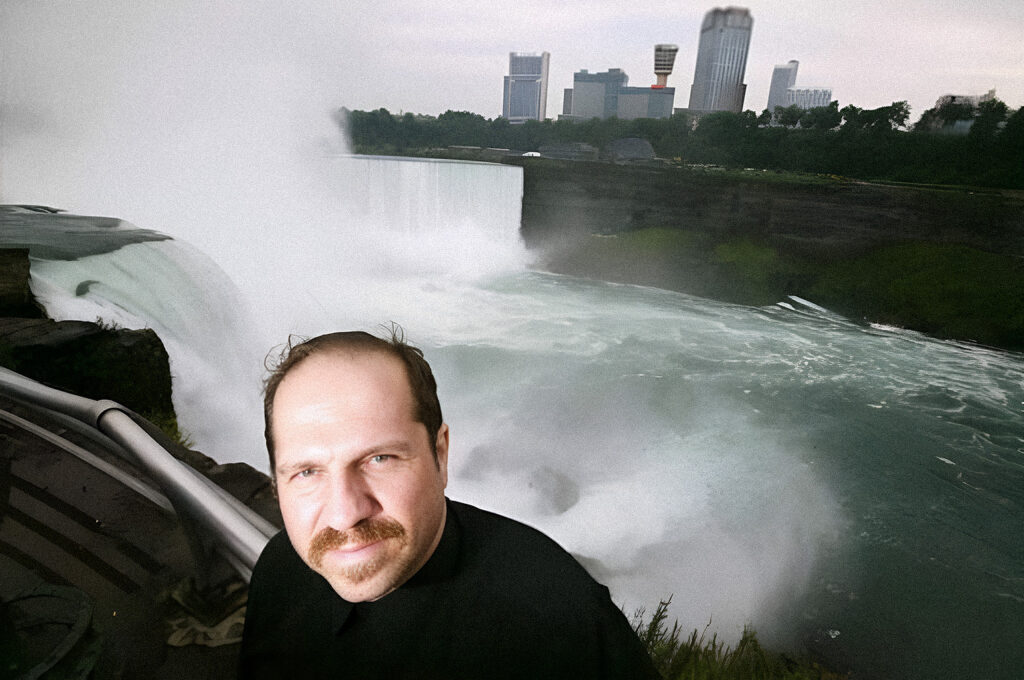

Until that point, Fieger was a fairly anonymous Oakland County litigator who was mostly known as the older brother of Doug Fieger, lead singer of The Knack and co-writer of the smash 1970s hit, “My Sharona.” But representing Jack Kevorkian made him famous in his own right.

Geoffrey Fieger reacted with outrage when his client was charged with murder, and a few months later, the charges were thrown out. He would go on to represent Kevorkian throughout the 1990s and eventually became just as famous as his client.

In 1998, Fieger dipped his toes in the political waters, running for governor in Michigan and winning the Democratic primary, profane and bombastic as ever. He was crushed by incumbent Republican Gov. John Engler that fall, as most notable Democrats refused to endorse him.

But with Fieger by his side in the 1990s, Kevorkian kept going. Between 1990 and 1998, he helped kill at least 130 people, and it’s fair to say that perhaps more than any person in modern times, he changed the narrative around death, dying, and the sanctity of life.

A recent Gallup poll found that 71% of Americans support a person’s right to die with a loved one’s help. A slightly smaller majority (66%) support what Kevorkian did, doctor-assisted suicide. But when Gallup first started polling on the issue of a doctor helping a patient die by painless means back in 1947, only 37% supported it.

Kevorkian certainly did his best to make suicide easy and socially acceptable for people who might be in pain or suffering. But even his supporters will admit he was a deeply flawed evangelist for the cause. Most of the people he helped die weren’t terminally ill. Some of them were just in pain or suffering from depression, which was all treatable. At least five of his dead patients had no disease at all, according to the autopsies.

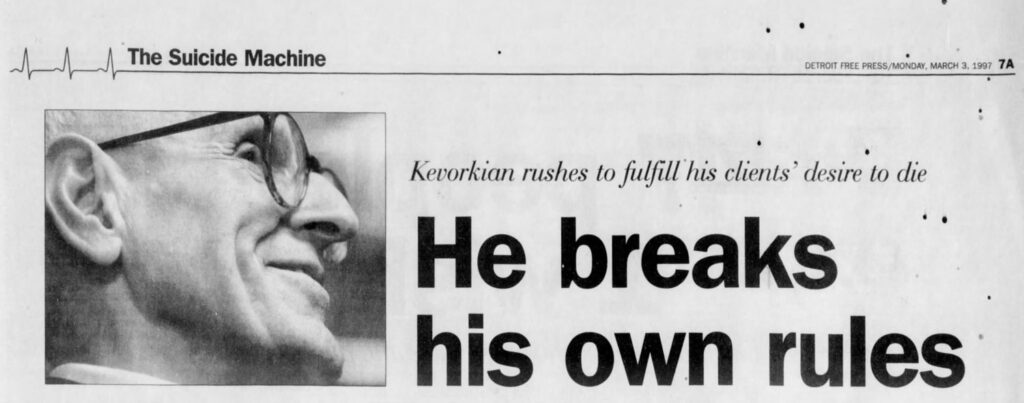

Some of his patients were hooked up to the suicide machine just a few hours after meeting Kevorkian for the first time. The Detroit Free Press found in 1997 that in cases where he could have referred a patient to a pain specialist, he sometimes let them push the death button instead.

Kevorkian eventually crossed the legal line, earning a criminal conviction and eight years in prison.

It happened in 1998, when CBS’s “60 Minutes” aired a video of Kevorkian giving a lethal injection to 52-year-old Thomas Youk, a man who suffered from Lou Gehrig’s Disease.

The State of Michigan charged him with murder, and the trial was a circus. Kevorkian and Fieger had parted ways, so Dr. Death insisted on representing himself at the trial. The judge kept trying to get him to change his mind and hire a lawyer, but Kevorkian wouldn’t budge. He further said that he was going to starve himself to death if he was sent to jail.

The conviction came down on April 13, 1999, and this time, Kevorkian couldn’t charm his way out of it. Judge Jessica Cooper sentenced him to 10 to 25 years in prison, telling him, “This is a court of law, and you said you invited yourself here to take a final stand. But this trial was not an opportunity for a referendum.”

He applied for parole several times and was denied repeatedly because he refused to say he wouldn’t commit the same crimes if he got out. Finally, in 2005, he told MSNBC’s Rita Cosby in an interview that he would stop helping people kill themselves (“I will not perform that act again when I get out,” he said), and he was granted parole in 2007.

Though he stopped hooking people up to his suicide machine, he continued to advocate for assisted suicide. He gave numerous lectures at colleges and universities and sought out any microphone or camera he could find.

CNN’s Anderson Cooper interviewed him in April 2010, asking him, “You’re saying doctors play God all the time?” To which he replied, “Of course. Anytime you interfere with the natural process, you’re playing God.”

A couple weeks later, the HBO movie, “You Don’t Know Jack,” premiered, starring Al Pacino as Kevorkian and Danny Huston as Geoffrey Fieger. It got great reviews, and Kevorkian himself walked the red carpet at the premiere next to Pacino, who ended up winning an Emmy and a Golden Globe for the role.

A little more than a year later, on June 3, 2011, Kevorkian died. He wasn’t hooked up to his suicide machine. Pneumonia and a blood clot took his life. He was 83.

Physician-assisted suicide is now legal in Canada, Australia, and several countries in Europe, as well as nine states (Michigan is not one of them). Kevorkian paved the way for all of this, considering the topic was barely debated before he came along.

Oregon became the first state to legalize physician-assisted suicide in 1994, the same year Kevorkian went on trial for the first time. In 2021, New Mexico became the most recent state to legalize it.

More than a decade after he passed, the legacy of Dr. Death appears alive and well.

Buddy Moorehouse teaches documentary filmmaking at Hillsdale College.