Gaylord — Every day, you carry the genius of Claude Shannon around with you. It’s in the emails and texts you send, the phone calls you make, the music and movies you stream. FaceTime, Instagram, Grok. Your Apple Watch. His contributions to the fields of mathematics, engineering, and computer science are what made the digital age possible.

But Claude Shannon is not a household name the way Einstein and Newton are. Despite shaping the entire tech industry, you’ve probably never heard of him.

That is, of course, unless you’re from Gaylord.

“You’re interested in Claude Shannon,” a woman says as she greets me from the back of the Otsego County Historical Museum in downtown Gaylord. She’s a volunteer curator and is here with her husband and their young granddaughter.

She walks me over to an exhibit in the center of the museum. “Claude Shannon” stands out in large letters on the wall. Gaylord is where he grew up.

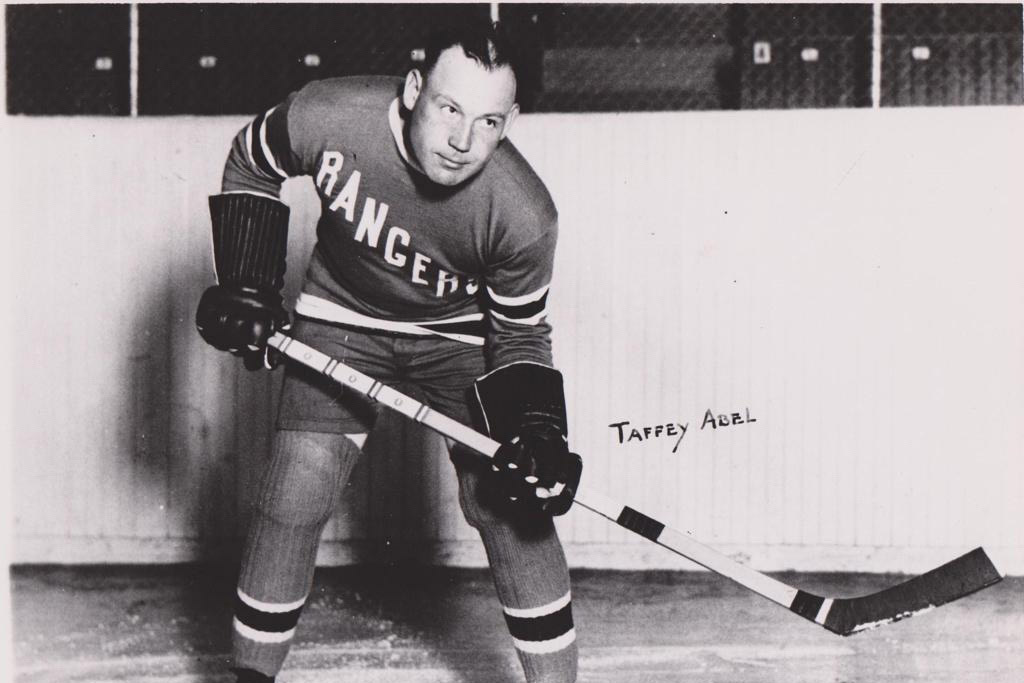

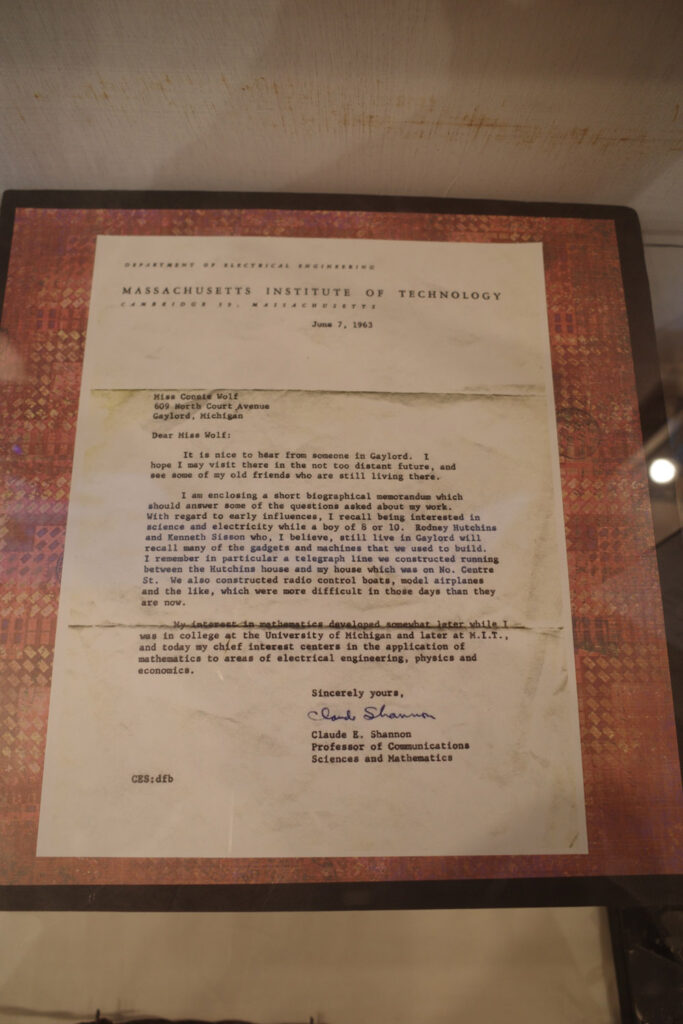

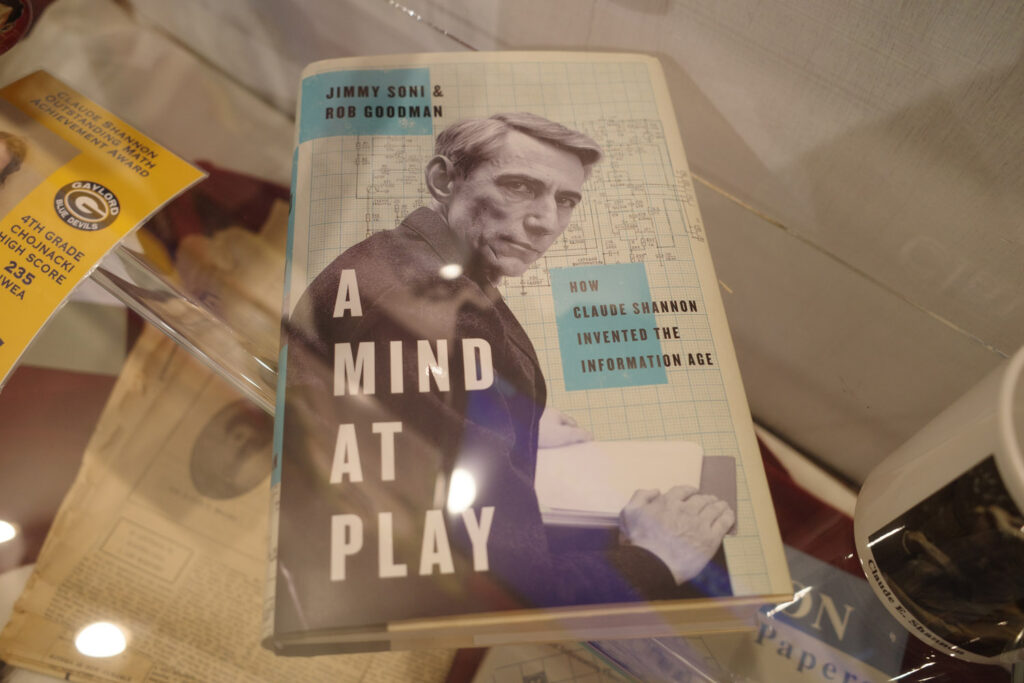

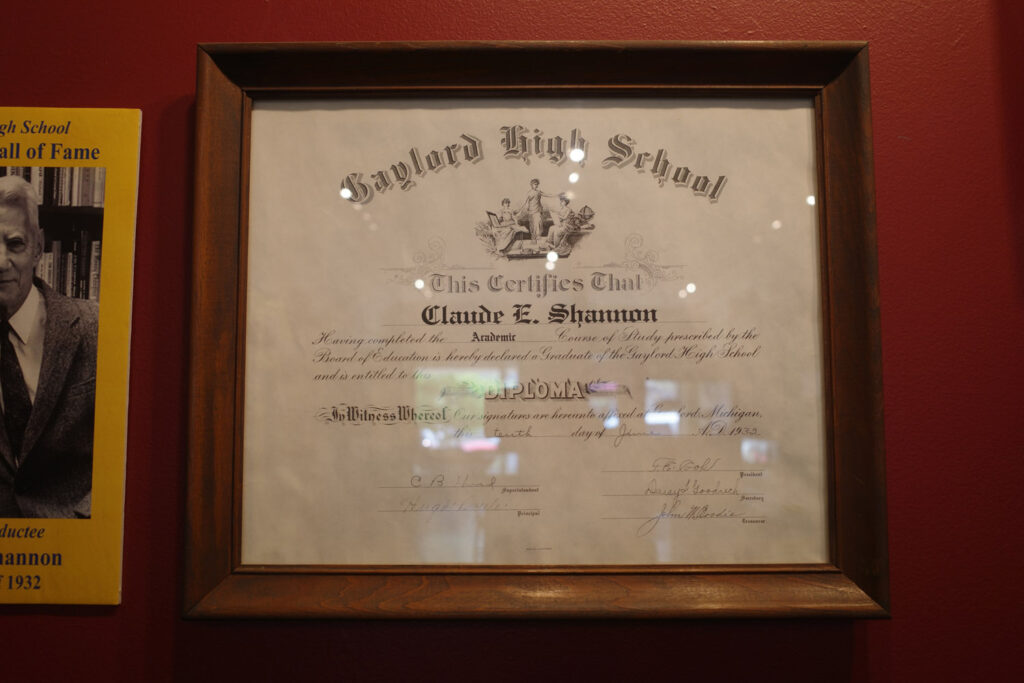

The curator and her young assistant show me a few things inside a glass display case: books, letters, newspaper clippings. A documentary about Shannon plays in a loop. His high-school diploma is framed below a photograph of his graduating class—just 29 students, with young Claude at the far end of the back row. Head slightly cocked, he looks as if he’s trying not to be noticed. Only now, a large blue arrow hovers above his head.

After completing high school in 1932, Shannon went on to earn bachelor’s degrees in mathematics and electrical engineering at the University of Michigan. A job posting for a research assistant who could run a “thinking machine” at MIT caught his eye after graduation.

He applied and got the job, staying at MIT for four years. While there, he wrote a groundbreaking master’s thesis, which proved Boolean algebra could be applied to circuit design. It would lay the foundation for all of modern digital computing.

In 1948, he wowed the world again with his paper, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication.” Scientific American called it the “Magna Carta of the Information Age.” In it, he explained how information—text, sound, pictures, video—can be quantified, organized, and transmitted. He also introduced the term “bit” (binary digit) for the first time.

I mention Shannon’s statue, which sits in Claude Shannon Park a few blocks down the street, to the curator. It’s a charming bronze pose depicting Shannon from the waist up, slightly hunched, hand to chin, deep in thought.

“There are five other statues just like it around the country,” she explains. “But we had the first. His wife Betty wanted us to have the first.”

Once you learn about Claude Shannon, you realize the vastness of his accomplishments. In addition to his theorems and writing, he also built one of the very first artificial intelligence machines (“Theseus,” a robotic mouse that could learn to solve mazes) and the first wearable computer (a device to help wearers cheat at roulette).

That one mind contributed as much as his is astounding. At the same time, I have to admit: I barely understand it.

I’ve researched his work extensively. I’ve read the bios, watched the documentaries, and even tried making my way through his 1948 paper (I got a few paragraphs in before I gave up).

I haven’t even come close to grasping the full scope of his breakthroughs.

Maybe I’m a little disappointed at that. But I think it’s also worth noting that it’s kind of the point: He understood it, and we don’t. Geniuses see the things the rest of us can’t. They ask the questions we don’t even know to ask. They dream in a world beyond the limits of our knowledge.

All I can wonder is: Where does all that brilliance come from? What makes a genius? How does a mind as dazzling as Claude Shannon’s come to be?

Of course, it’s often just the luck of the draw. But in our hustle-culture age, one might assume his upbringing also involved private tutoring and special summer camps as a kid; an organized life of packed extracurriculars, rigorous study, and perfect grades. With maybe some Adderall thrown in to keep him on track.

Only, that’s not at all what happened in Shannon’s life.

What’s repeatedly emphasized about him is his love of play, his endless curiosity, his wandering mind, and constant questioning.

“I’ve always pursued my interests without much regard for financial value or value to the world,” he once stated in an interview. “I’ve spent lots of time on totally useless things.”

His daughter echoed the same: “The foremost characteristic of my father was playfulness.”

Shannon’s childhood was wild and free. Gaylord was a manufacturing town, and little Claude loved to build and tinker. He and his friends created a telegraph system between their houses with barbed wire run along a rural fence line.

He loved code-breaking puzzles and reading. Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” was his favorite book, with all its nonsense and playful logic. In college, he enjoyed the poetry of E.E. Cummings and T.S. Eliot, and an early girlfriend said he was constantly listening to jazz. He loved its unpredictability.

In later years, his home workshop was filled to the brim with inventions: a chess-playing computer, toys that juggled, a rocket-powered frisbee, and a flaming trumpet made for his son’s talent show. He taught himself and both of his kids to juggle, appreciated a good prank, and rode unicycles around the halls of Bell Labs.

Could it be that all that playfulness, curiosity, and tinkering were exactly what made his mind so extraordinary?

It seems foreign compared to today. Now young people are on a tight leash. Toddlers are put into school at 2 years old to secure their preschool spots, iPads have replaced tree climbing, and “difficulty focusing” or a reluctance to “sit still” are met with diagnoses and medications.

It makes you wonder whether a Claude Shannon could even exist today. Or whether his creativity and spark might have been snuffed out early on. If not that, perhaps he might not have even been born. His parents, after all, may have looked at his Orchid embryo profile and found bio-markers for Alzheimer’s—the disease he indeed succumbed to at age 84.

No one can know, of course, but it’s a troubling thought.

We can only hope that in this digital age that the genius of Claude Shannon helped create, the sterility of hyper-optimization doesn’t shroud life’s delightful uncertainties, nor the many rabbit holes that await curious minds like his.

Faye Root is a writer and a homeschooling mother based in Northern Michigan. Follow her on X @littlebayschool.