Detroit — Finding a story is often harder than writing one, and three of mine fall through before dinner. This weekend was meant to include kitesurfing, gun shooting, and hanging with a UFC fighter. But death came in threes. No time to mourn. I can still improvise. Isn’t this what good journalists do? They tiptoe into shadows to find the stories that others miss. Unfortunately, many people in the business of information dissemination share the same job title. In the next few days, I will meet both types: the fake-news “journalist” and a real investigator.

For now, I’m in my hotel room self-harming—watching Rachel Maddow compare SS French collaborators with the Republican Party for supporting Donald Trump. I flip channels. There’s only pharmaceutical commercials.

Outside my window, in a bad part of town, a black man with dreads is standing on the road with jumper cables. No one is stopping to assist him. His vehicle is missing half the front end, with the radiator nakedly exposed, and all four tires are completely deflated. Inside the car is a woman wearing men’s boxer briefs and a shower cap, smoking Newport Menthols, with three kids on her lap. I yell to see if he needs a boost (knowing the answer but wanting an invitation).

“I work in private equity,” Florian tells me, as he links our car batteries, “and that’s my baby mama.” Astonishingly, his speech switches between street slang and corporate dialect. Florian explains his business, interchanging ghetto terms and the boardroom jargon: He supplies “capital” (cash) to his “clients” (hustlers), who then distribute various “products and services” (drugs and women), for which Florian receives a handsome “return on investment” (stacks and bands). We get to talking. His car starts.

Later, I call Florian several times. He first postpones, then supplies excuses, and then finally lets his phone ring without answering. When we spoke last, he seemed a little scared and reluctant to meet up. Maybe I’ve given him the impression that I’m a cop? Maybe meeting a real gangster on the street is like meeting dangerous animals in the wild: They can be more scared of you than you are of them.

Now what can I do? Little else but kill time drinking in Corktown. But there are only so many establishments you can visit, sipping on light beer and looking for interaction, before you start to feel desperate.

*

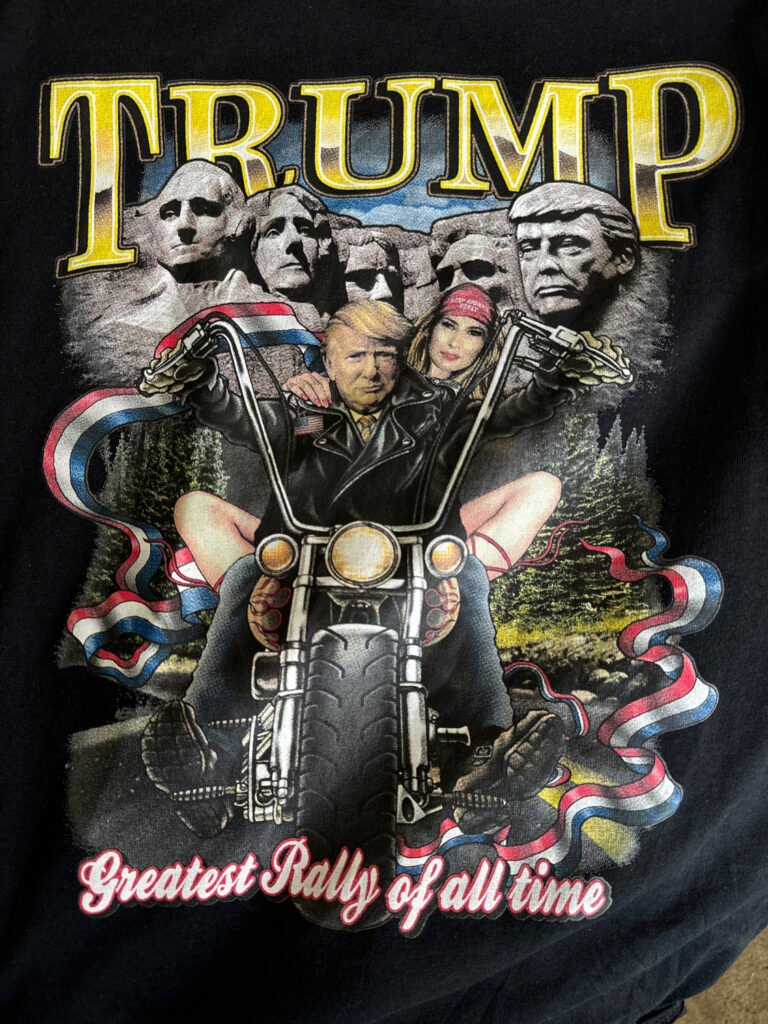

I’m in the enclave of Hamtramck when I receive a message from a friend: Donald Trump is going to be at the 180 Church to address the black community. I was trying to avoid party politics this weekend, but screw it—I’m finding nothing else right now. I get into my car and drive across the city.

There must be a small crowd because I find parking easily. Smash-and-grabs are so common here that leaving my luggage in my car would be asking for it. I bring my duffle bag and backpack inside, where the Secret Service oversees my entrance. They hardly look at my bags, let alone search them, and casually wave me through. I write on my iPhone’s Notes (on June 15, nearly a month before the assassination attempt at a similar rally): “Secret Service did not check my belongings. Managed to bring inside a knife. Surprising.”

I sit in the designated press area right next to the U.S chief political correspondent for the Daily Mail. He’s a dour looking Englishman who carries some weight in the abdomen, in that uniquely British way, which hints at after-hours pints for stress relief. For 30 minutes, I ask him a torrent of questions, which he courteously, if reluctantly, answers. He doesn’t ask me anything in return, or expand on his laconic answers, or demonstrate any curiosity toward his audience. I ask whether he’s going to be writing about this rally. He tells me that most of his piece is already written and that he’s only here as a matter of procedure. He adds that he might include more if Trump bleats out something obscene. He says it as a matter of fact, not with smug liberal pretension.

Trump is late, so I try digging a little deeper:

Who is your favorite writer?

“I don’t have one.”

What about cultural commentators or pundits whose insights you find interesting?

“I don’t read anymore. I used to when I was young.”

Who were these early influences?

“I can’t remember their names.”

This goes on for long enough that I’m surprised he continues talking. He’s not irritated by me, and he participates in my futile interview with catlike indifference. I eventually relent and tell him what I really think, which is that he seems jaded. He agrees and responds that 20 years in journalism will have that effect.

When cynicism can be so severe that a writer stops reading, it’s a sign that life’s spark is gone, like when a dog loses his appetite for food near the end. For the rest of the rally, he stares ahead with a ceramic countenance while his computer automatically transcribes the speech. He’s suffering from terminal apathy.

*

I meet Charlie LeDuff the next morning in Royal Oak. You’d never know that he has a Pulitzer by looking at him. With hair slicked back and held in place by sunglasses, some thick cargo shorts, a well-worn T-shirt, a very good tan, and lean muscle, he looks like a roofing foreman. But all his accolades make perfect sense once his mouth opens.

It’s our first encounter, and he immediately enters my car with a plan. “This is how this works, we’re gonna run some errands while we talk.”

Besides meeting me today, LeDuff is caring for someone in the hospital. So now we’re going shopping. First, we get flowers from a grocery store. Between selecting a pink bouquet of flowers (“Never get your woman roses, it’s too cliché”) and handing the clerk an insufficient $1 bill instead of a $20 (“Come on, it’s a Biden $100…inflation!”), he’s asking me questions about my job, about journalism, and about the world. I understand what he’s doing: He’s getting puzzle pieces that he can collate into a bigger picture of me. It’s obvious that even if you stripped him from the masthead, LeDuff is a journalist at his core. It’s not his job, it’s a vocation.

We arrive next at New York Bagel (“For the nurses. Gotta keep them happy”). While waiting in line LeDuff is talking with customers, introducing himself to strangers, buying me coffee, and telling the working girls behind the counter a joke concerning an avaricious rabbi and a pederastic priest. He has a very good sense of humor. It probably keeps him sane.

We go to the parking lot and smoke some tasty Winston Tobacco & Water cigarettes, which, according to LeDuff, “are similar to American Spirits, which used to advertise ‘additive-free’ and ‘natural’ until they got busted by the FDA,” before adding, “but, you know, I still fall for marketing.”

He then tells me about a story he’s been working on. A murder mystery in which a woman was stabbed eight times in the head and neck. She had been the president of a synagogue. Because the attack occurred exactly two weeks after the October 7 Hamas raid on Israel, many were searching for someone motivated by antisemitism. Even Hamas was alleged as the perpetrator.

That was soon ruled out.

A suspect eventually was found and charged for the crime. However, in LeDuff’s mind, things didn’t add up: The accused had a history of petty thievery yet was found without plunder; the nature of the attack (stabs to the head) seemed to suggest a crime of passion; the boyfriend then confessed to committing the murder after a bad night of antidepressants and cannabis, but then, oops, retracted the confession. These inconsistencies and curiosities tickled his funny bone. So he did what few other journalists do, he became the victim, the criminal, and the detective.

According to the police, the accused was a quarter mile away from the crime scene, obtained from CCTV footage, where he was observed crossing a bridge. It was only 4 minutes after the motion detector was triggered inside the victim’s home.

But LeDuff mapped out the distance independently, between the murder scene and the accused’s location, and found it to be more than a third of a mile away, which is almost two football fields further than the originally accepted quarter mile.

LeDuff, who’s a runner, then laced up his trainers and sprinted from the victim’s front door to a third of a mile away. It took him 2 minutes and 30 seconds at a full sprint. And this was only running from point to point. There was also time spent entering the home, struggling with the woman, stabbing her, and leaving the unit. According to a detective’s analysis, as it was presented to the jury, the accused was sprinting for only a minute, which means he was covering ground like a professional track runner. To the pile of absurdities, LeDuff heaped on another. He says the best homicide detective in the country came to the provisional conclusion of “no f***ing way” when he showed him the facts.

LeDuff’s instincts were vindicated. A month after we spoke, the judge dropped the murder charge, leaving the family confused and asking: Who then killed her?

The murder is not yet solved.

But what’s most amazing for me is that LeDuff is not writing about the case. He wasn’t commissioned by a publication or employed by an investigative team when he started prodding and poking at the story. Instead, he’s invested in it for a simple reason, which is that he can’t stand the pungent smell of bullshit.

He now must go, and throughout our meeting he’s been receiving some important calls. People high in government. Others who seem to be providing highly sensitive information. But he’s unfazed.

Later, I ask him how he remains steadfast against such pressures. He gives me a simple formula for good journalism: “It’s all you need: One, you must be accurate. Two, you must be interesting. And what’s interesting can never detract from what’s accurate.”

Mitch Miller is an adventure writer and conflict journalist. He’s more than happy to join in on any extreme activity, and can be reached at mitchenjoyer@gmail.com. Follow him on X @funtimemitch.