Just a dozen or so years before Henry Ford started building automobiles here, stagecoaches were still operating in Michigan and there were still people robbing them. And the tale of Michigan’s last stagecoach robber is an epic one.

Reimund Holzhey, a German immigrant, held up a stagecoach in the western Upper Peninsula in 1889 and killed a man in the process. He spent 24 years in prison, during which time he got four of his fingers shot off. When he got out, he became a photographer and tour guide, then moved to Florida and lived in total anonymity before taking his own life in the 1950s.

Oh, and he also had brain surgery while in prison, an operation that relieved pressure on his cranium and supposedly turned him from a bad guy to a good guy overnight.

Reimund Holzhey was a nationally famous outlaw, a legend in his own time who brought a taste of the Old West to the Great Lakes State. When you talk about the colorful criminals we’ve had in our state, he ranks at the very top.

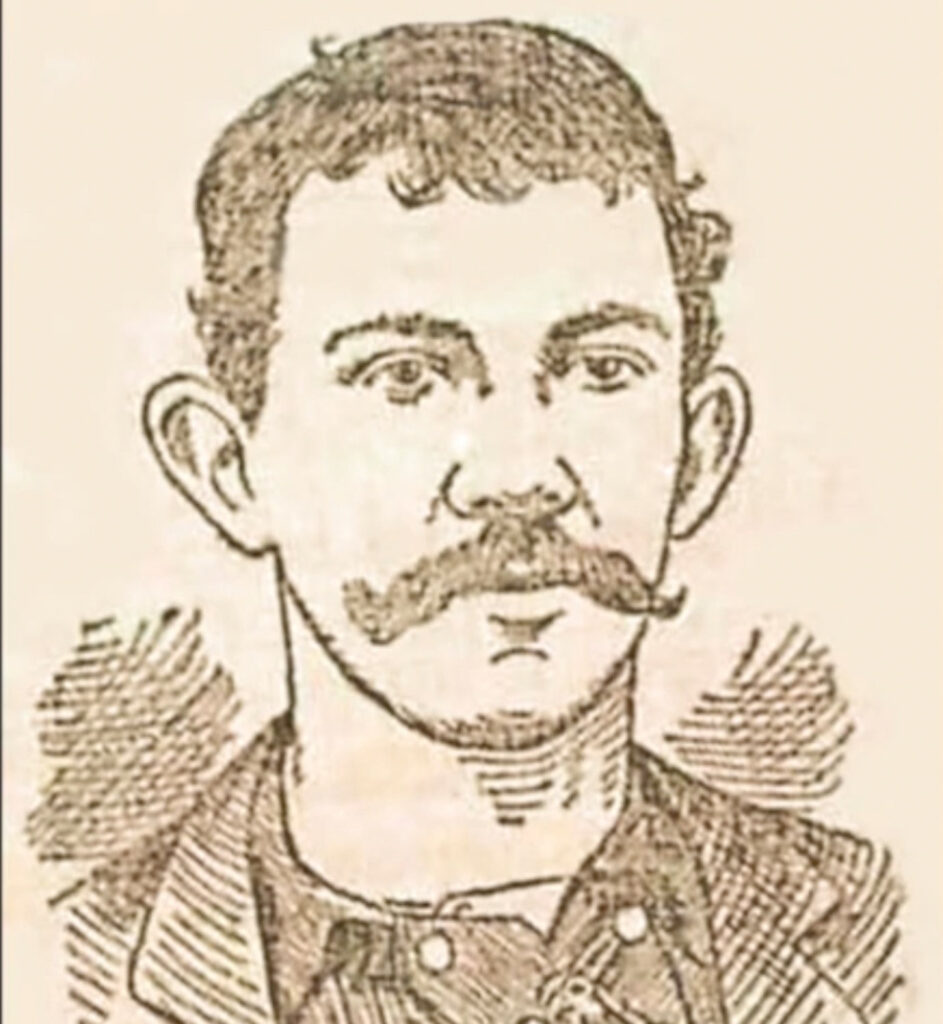

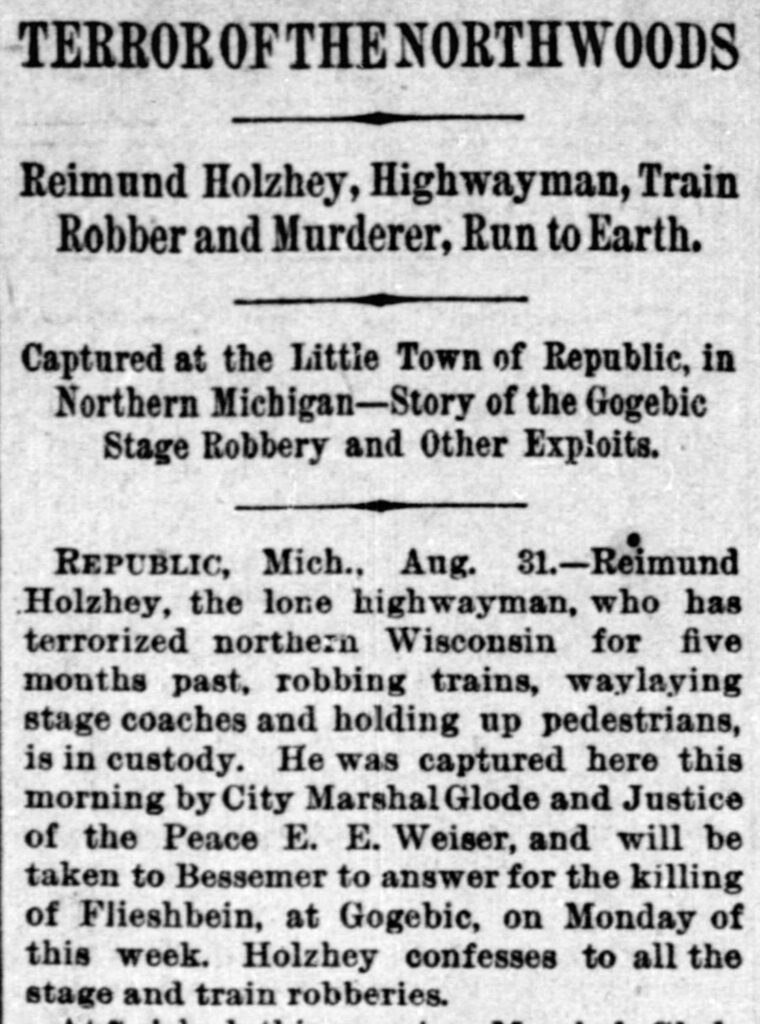

Holzhey’s story begins in Meiningen, Germany, where he was born in 1866. He came to the U.S. at age 18 and settled in northern Wisconsin. After a few years working as a lumberjack, he turned to a life of crime and started robbing trains and stagecoaches. From April to August 1889, when he was 23, he pulled off several robberies in Wisconsin. Wanted posters started popping up all over the state featuring a sketch of the outlaw with the bushy mustache.

His infamy was growing, and the train and stagecoach companies started offering big rewards for his capture, dead or alive. By late August, the reward for his hide had grown to $2,500—about $88,000 today. Even regular folks in northern Wisconsin were afraid to go outside.

“A man of tremendous energy and a clever woodsman, Holzhey would commit a robbery and disappear, only to turn up the next day 20 miles from the scene,” a later article from 1910 said. “No man went on a journey without a gun, for fear of meeting the bandit.”

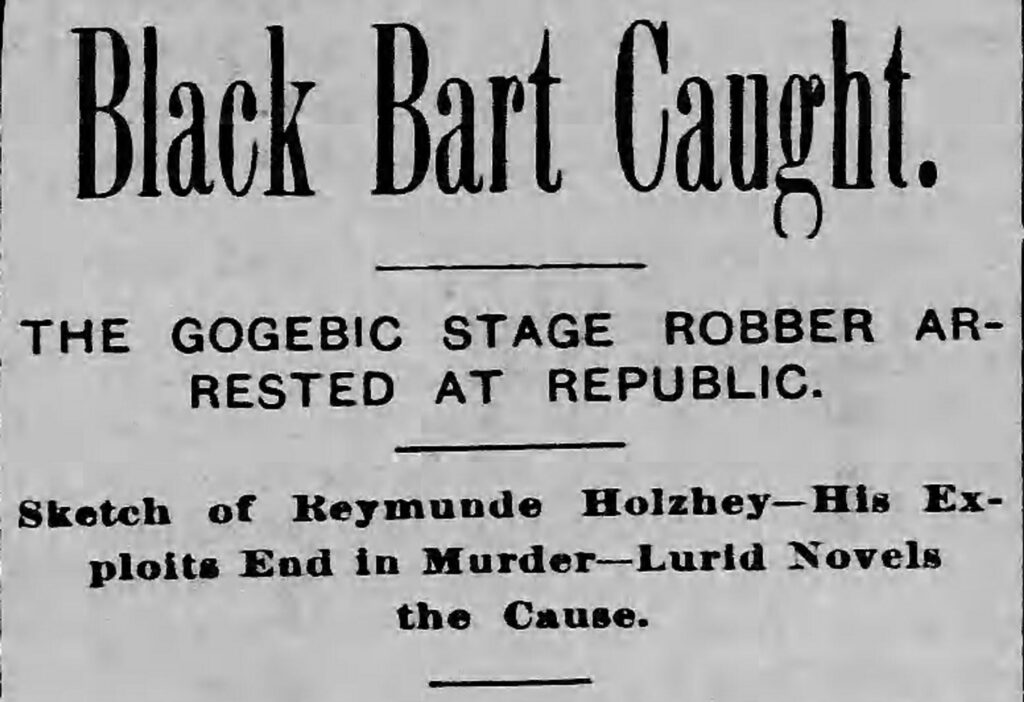

The papers started referring to him as Black Bart, the same name given to a stylish Englishman named Charles Boles who had been robbing stagecoaches in California and frequently left poetic messages behind. Holzhey was known as the Black Bart of the Northwoods.

Unbeknownst to the authorities, by late summer, Holzhey had moved his base of operations from Wisconsin to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, where he was looking to make another big score.

He spent the night of August 25, 1889, at the Gogebic Hotel, just over the Wisconsin state line. He overheard three bankers on vacation talking about how they were going to take the stagecoach the next day down to Lake Gogebic, a summer resort. Holzhey got up early the next morning and set out for the woods. Bankers carry a lot of money, he figured, so this would make for the perfect score.

When the stagecoach passed by at 11 a.m. the next day, Holzhey stepped out from behind a tree holding two pistols, aiming them right at the driver. Holzhey demanded that he stop the coach and then opened the door and pointed the guns at the three bankers and one other passenger inside.

“I want to make a collection from you fellows,” he said. “Gentlemen, shell out!”

One of the bankers was a man from Illinois named Adolph G. Fleischbein, and he didn’t want to give up his money so easily. He pretended to reach into his pocket for his wallet but came out with a revolver instead.

“Instead of bringing up his pocket-book, he clenched a pistol in his hand and began firing at the robber,” the Green Bay Press-Gazette reported. “Instead of being overcome by the suddenness of the intended victim’s move, the robber returned the fire.”

It was a good, old-fashioned Wild West shootout right there in the U.P. woods. Fleischbein shot several times and didn’t hit anything, but Holzhey fired and hit the banker twice, including a direct shot to the hip. Fleischbein was taken to the hospital in Bessemer, where he bled out and died later that night. That made Holzhey a murderer.

When the local lawmen showed up to investigate, they realized that the description of the robber matched the description of the outlaw who had been terrorizing Wisconsin all summer. They knew they were looking for Reimund Holzhey, and a posse was formed.

Holzhey spent a couple nights in the woods but eventually found his way to Republic, a small town in the middle of the U.P. about 100 miles east of Lake Gogebic.

There were maybe 200 people living in Republic at the time, so newcomers tended to stand out, especially a scruffy guy with a bushy mustache who looked like he’d been living in the woods. The local judge, Edwin Weiser, was the first one to spot Holzhey on the street. All the newspapers in Michigan had carried stories of the stagecoach robbery and a description of the robber, and Judge Weiser was sure that was the guy.

He sent someone to get Deputy Sheriff John Glode and Marshal Pat Whalen while he kept an eye on Reimund. They telegraphed the authorities in Bessemer, asking them if this guy might be Holzhey, and when they didn’t get a quick response, Glode and Whalen decided they needed to act right away, lest he slip through their fingers.

Glode and Whalen pounced on Holzhey and arrested him. He had Adolph G. Fleischbein’s pocketbook and some of the other robbery booty on him, so they knew they had their man.

Newspapers across the country carried the news the next day: “Black Bart Caught.”

Before turning him over to the authorities back in Bessemer, though, Deputy Sheriff Glode and Marshall Whalen decided to make the most of it, since this was pretty much the biggest damn thing that had ever happened in Republic.

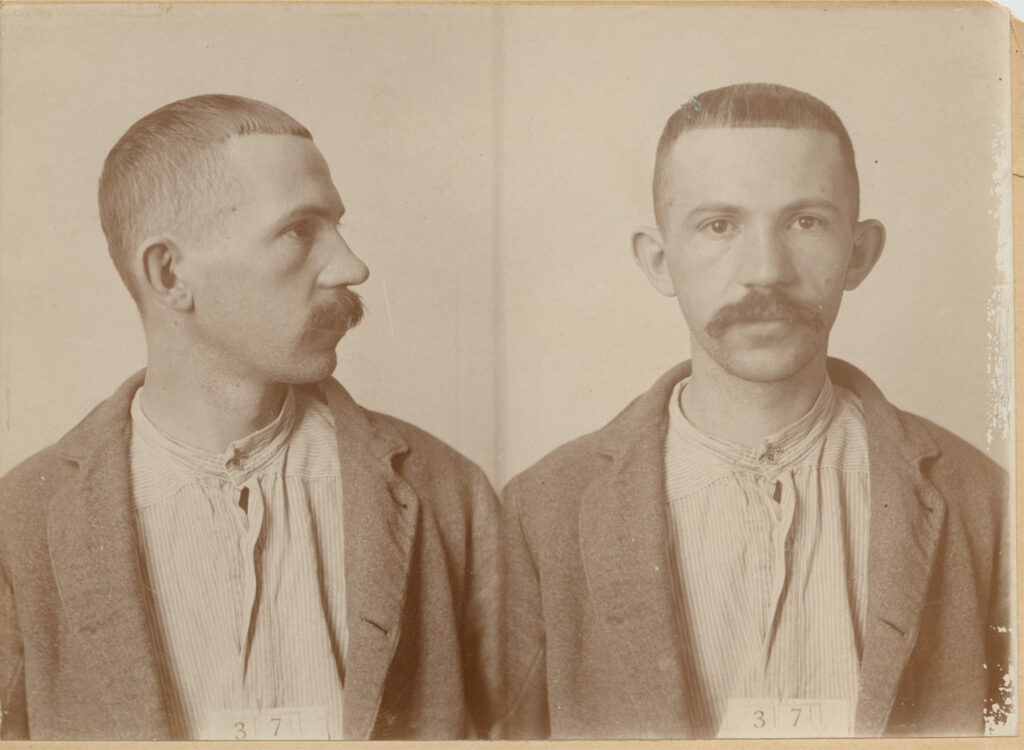

They contacted a photographer named William Whitesides, a man from Ironwood who was well-known throughout the Upper Peninsula. They brought him to Republic and had him take a posed photo of them standing proudly on either side of the handcuffed Holzhey, looking the part of heroic Wild West lawmen.

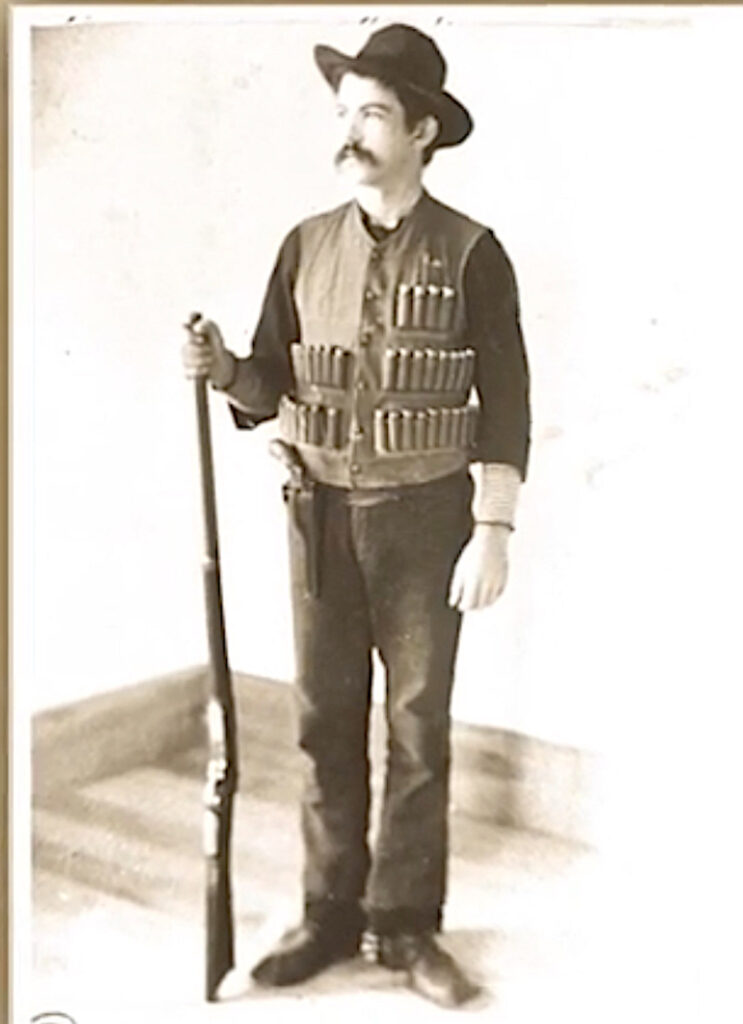

Then they took it one step further. Inspired by a well-known photo of Billy the Kid, they figured that Holzhey needed a criminal portrait of his own. They had Whitesides take a photo of Reimund packing an empty pistol and holding a rifle, while wearing a vest filled with ammunition that didn’t fit either weapon. Black Bart’s legend was now complete.

Newspapers around the country were having a field day with the story. Some of them, including the Indianapolis Journal, were flat-out rooting for Holzhey to be hauled out of his cell by an angry mob.

“Streets and saloons are crowded to-night, and there is much talk of lynching him before the stage which meets the train at North Bessemer reaches the city,” the Journal wrote. “No one will go to bed until the prisoner is either safe in the county jail or dangling from some convenient bough in the forest.”

Thankfully for old Reimund Holzhey, that didn’t happen. Instead, he went to trial three months later, and it took the jury all of 45 minutes to find him guilty of robbery and murder. He was sentenced to a life of hard labor.

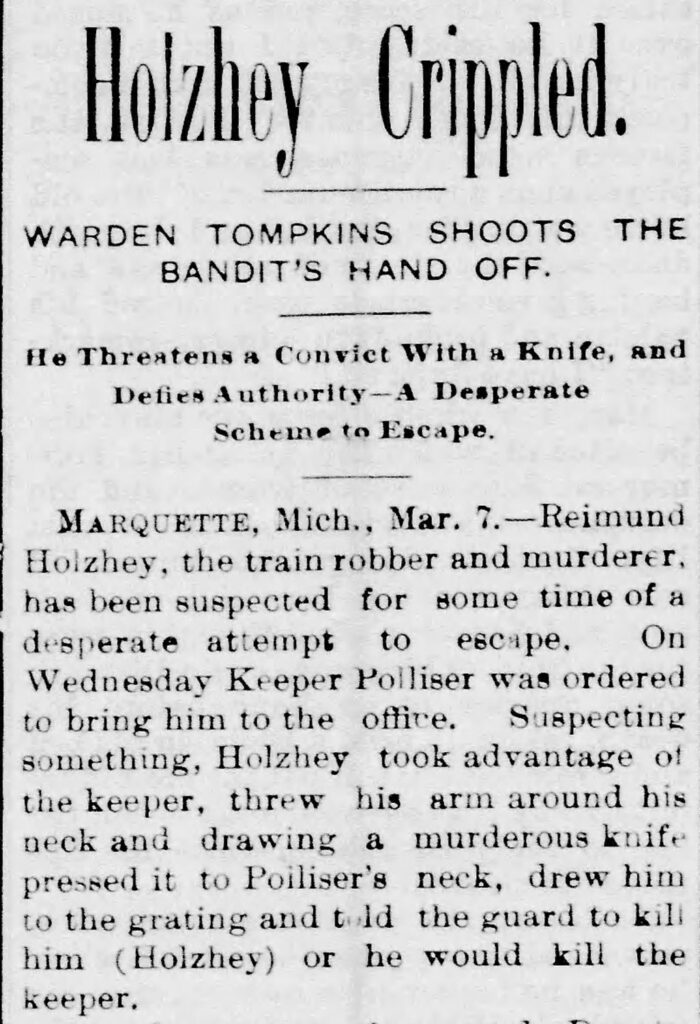

Black Bart was sent to prison in Marquette, and just six months later, he got in huge trouble again. He somehow got his hands on a knife and put it to the throat of a fellow inmate, threatening to kill him if he wasn’t let out. Instead, the inmate broke free and the warden took a shot at Reimund, blowing off four of the fingers on his right hand. Ouch.

From then on, Holzhey behaved himself and eventually even became a model prisoner. He was put in charge of the prison library, became the editor of the prison newspaper and learned how to do photography.

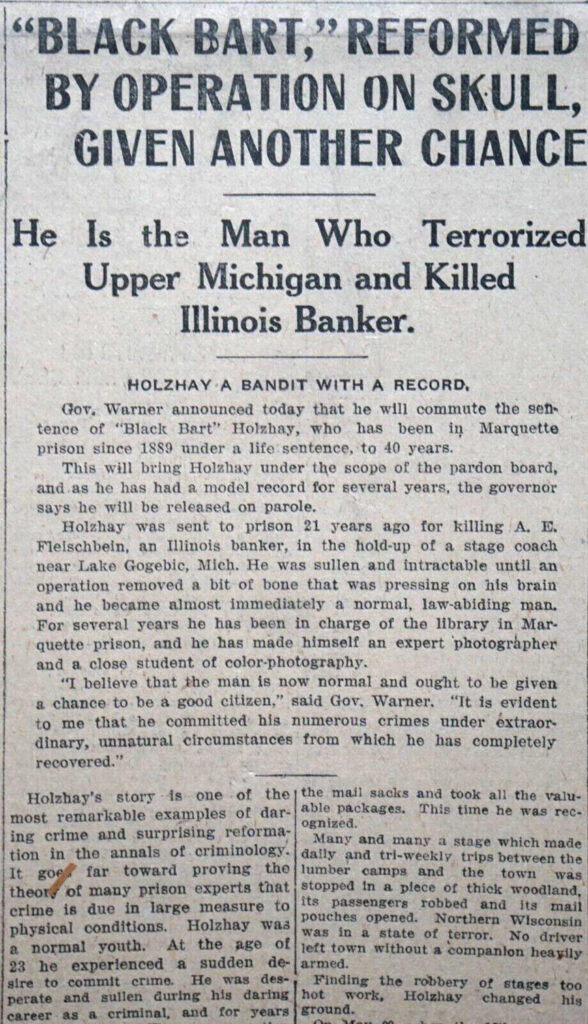

Holzhey made headlines again in 1910, a full 21 years after he’d gone to prison, when he underwent an operation to remove a bit of bone that had been pressing on his brain since he was a kid. The operation was a success, so much so that it convinced Michigan Gov. Fred Warner that was no longer a threat to society.

Holzhey had been claiming for years that he was only a criminal because there was something pressing on his brain, and now that the pressure was relieved, he declared himself cured. Gov. Warner bought the story and issued Holzhey a pardon.

“I believe that the man is now normal and ought to be given a chance to be a good citizen,” Warner said. “It is evident to me that he committed his numerous crimes under extraordinary circumstances from which he has completely recovered.”

The state required Holzhey to serve three more years, so he got out in 1913 at age 47 and started a photography business in Marquette under the alias of Carl Paul (figuring nobody would ever hire the famous murderer Reimund Holzhey to take their family photos).

He did that for a few years, and in 1917, he went back to his original name and moved to Yellowstone National Park, where he took photos of tourists and gave them tours of the park.

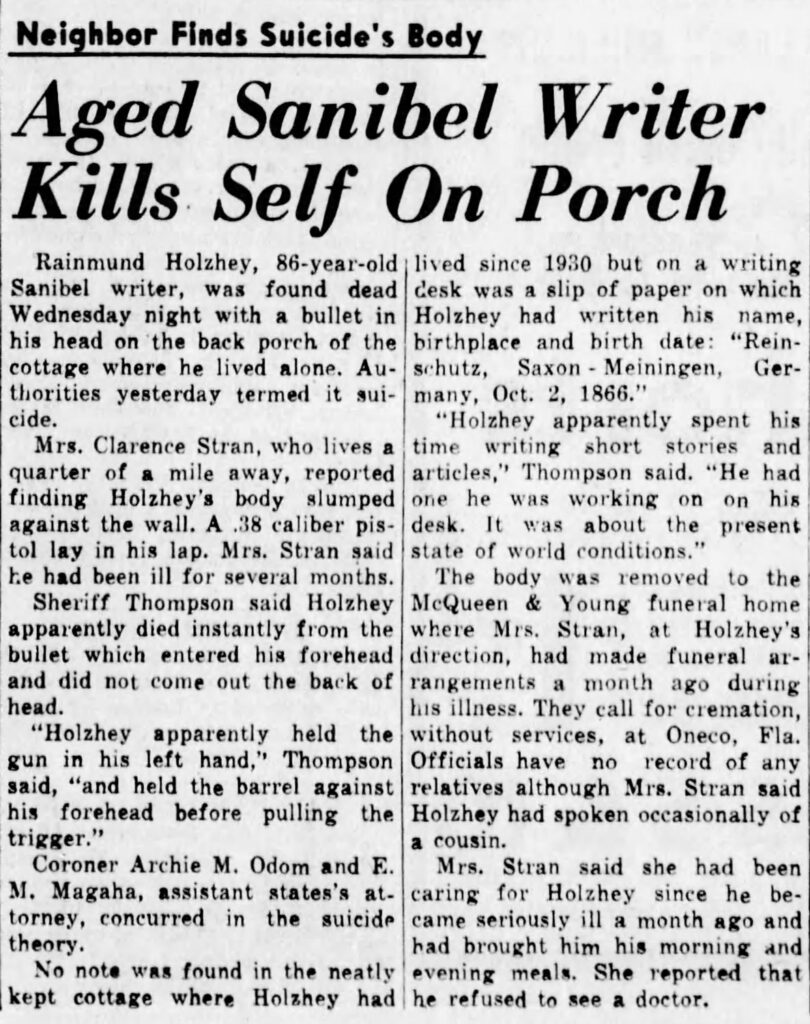

In 1930, Holzhey moved to Sanibel Island in Florida, where he bought a small cottage and started writing. The locals fell in love with the gruff and charming old man with the thick German accent.

It also appears that nobody in Florida knew that the gruff and charming old man was actually a stagecoach robber from Michigan who had killed a man in a shootout. His torrid past had not followed him to the Sunshine State.

When Holzhey died in 1952 at age 86, having shot himself on his front porch following a long illness, the Ft. Myers News-Press wrote a front-page story that covered the suicide in detail but didn’t include a word about his criminal past. Holzhey was simply described as an “aged Sanibel writer.”

He might have been that, but he was so much more.

Back in Michigan, meanwhile, Holzhey’s legacy remained strong. In 1969, a full 80 years after the state’s last stagecoach robbery, the kids at White Pine Elementary School in the far western U.P. celebrated Michigan Heritage Week in May by putting on a series of historical skits.

The Ironwood Daily Globe reported on it: “An outstanding presentation was Mrs. Zarimba’s fifth graders’ enactment of the last stage robbery in the Midwest, which took place near the Gogebic Station in 1889. Reimund Holzhey, portrayed by Tammy Windsor, shot Adolph G. Fleishbein, enacted by Marty Kowaleski.”

You know you’re a legend when elementary school kids start doing skits about you. We’ll assume that young Tammy Windsor had an appropriately bushy fake mustache.

Buddy Moorehouse teaches documentary filmmaking at Hillsdale College.