There are more than 170 species of fish in the Great Lakes, but two of them have caused a hell of a lot of trouble.

The sea lamprey has been the worst. An eel-like monster, it uses its rows of concentric teeth to latch onto native fish and then it sucks the life out of them. Until a scientist from Rogers City named Dr. Vernon Applegate discovered a way to kill them in the 1950s, sea lampreys were on the verge of destroying the fishing industry in Michigan.

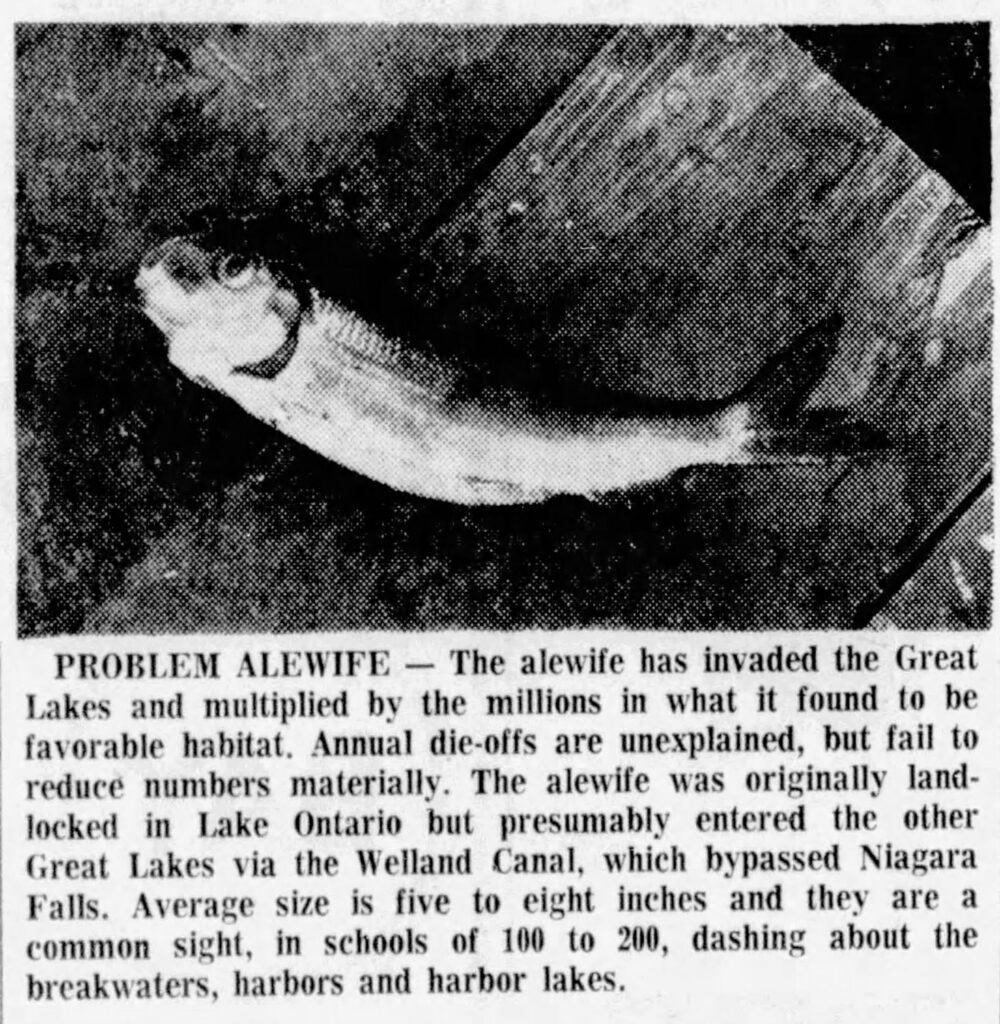

Then there’s the alewife. Described by one reporter in the 1950s as a “black sheep member of the herring family,” this small fish has been a curse for the Great Lakes, with only a tiny silver lining.

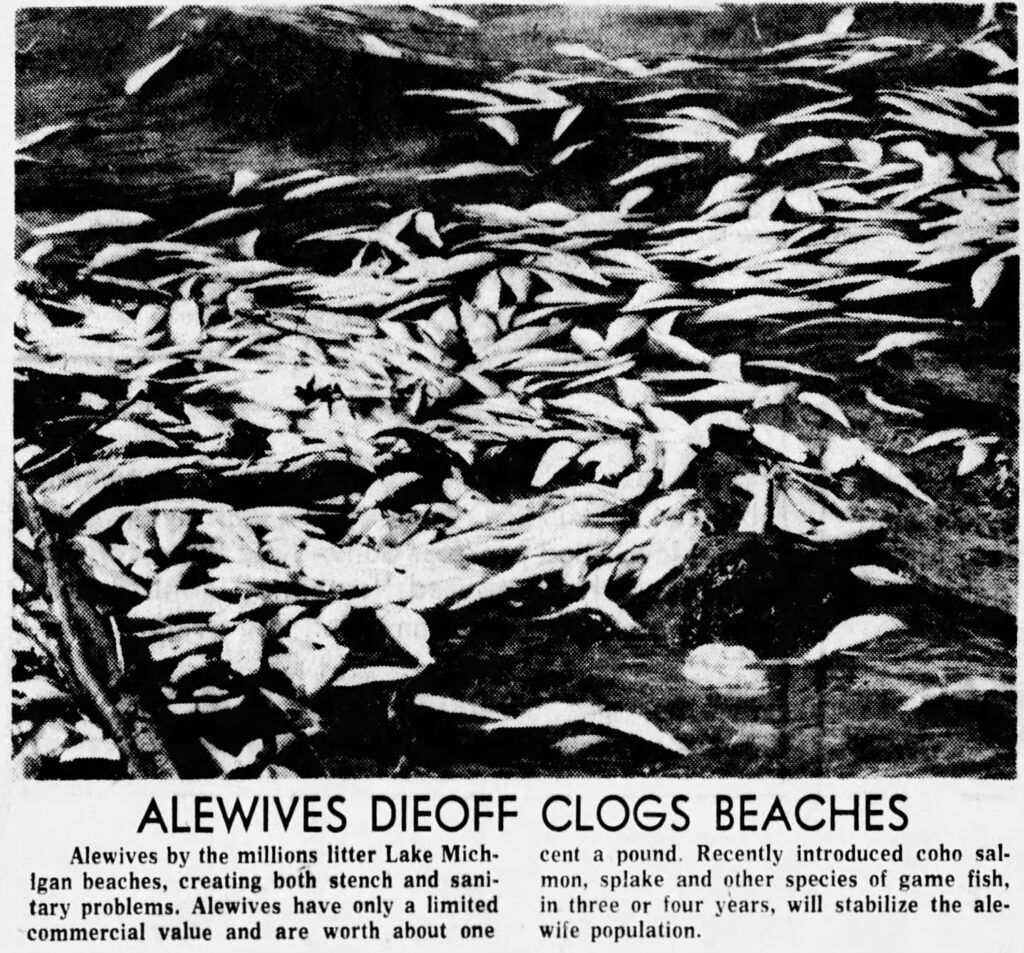

Since they invaded in the 1930s, alewives have at times reproduced so rapidly that they’ve washed up on shores in rotting heaps and choked out most of the native fish in the Great Lakes. They wreak havoc on perch, walleye, and lake trout by eating their eggs and competing with them for zooplankton—tiny organisms that native fish eat to survive.

In the 90-some years since, it’s been a nonstop battle for how to deal with them. If you’re looking for a villain in the story, you can blame Canada. Sort of.

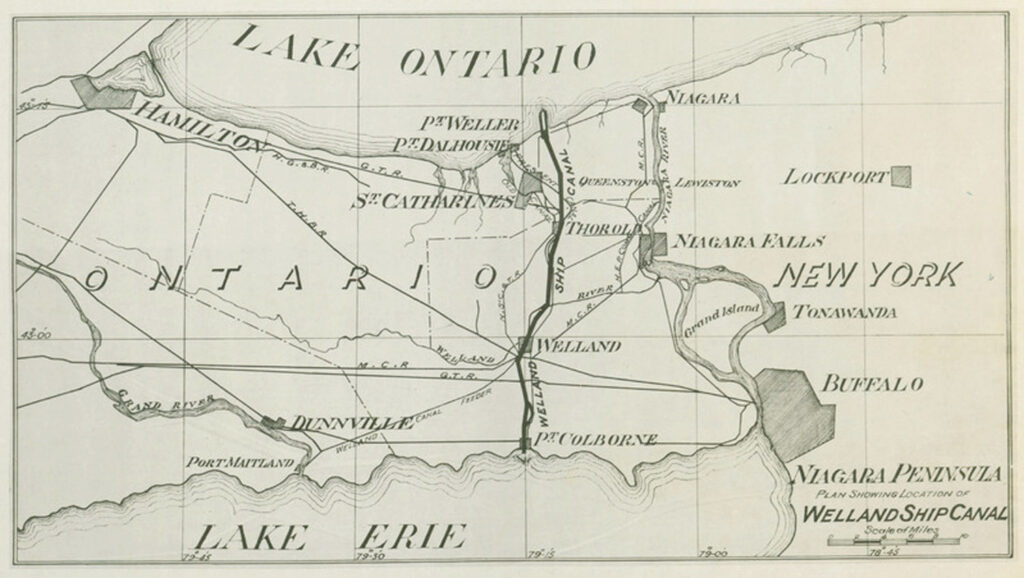

It’s all because of the Welland Canal, a 27.6-mile trench in Ontario, just west of Niagara Falls, that opened in 1829 and expanded several times since. The canal connects Lake Ontario with Lake Erie and makes it possible for a cargo ship to sail from Duluth, Minnesota, all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. The canal also made it possible for sea lampreys and alewives to enter the Great Lakes.

Sea lampreys and alewives are both saltwater fish that long to be freshwater fish, but before the Welland Canal was deepened in 1919, they couldn’t make it past Lake Ontario. They were stuck at Niagara Falls.

The expansion of the Welland Canal changed all that, and alewives started showing up in Lake Erie in 1931 and the other Great Lakes soon after that.

The alewife invasion didn’t seem to be an issue at first, and The Detroit News even seemed a bit giddy about it in this 1936 article: “Another exotic fish has invaded the Michigan waters of the Great Lakes, following rather closely on the heels of the Atlantic smelt and the lamprey eel. It is the branch herring or alewife… If it ever becomes as abundant as the smelt, it will add another good food fish for our lake and stream fishermen.”

It didn’t work out that way. The alewife wore out its welcome within the next couple decades.

A story in the Lansing State Journal on Dec. 7, 1958, spelled it out: “Commercial fishermen on the Great Lakes are facing invasion of a fish… the fish causing all the trouble is the alewife, a lean, sharp-finned pest which has almost no market value but is taking over space and food belonging to the lake herring.”

By the 1960s, alewives had almost totally taken over the Great Lakes. “Experts estimate that Lake Michigan alone contains 15 billion of these fish,” the Grand Haven Tribune reported in 1967. “The alewife, by weight, represents 90 percent of all the fish in the Great Lakes.”

They would die off by the millions every year, too. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, beaches all over the Great Lakes would see them wash up on the shores in droves. It was disgusting.

The sea lamprey had started the task of killing the native fish in the Great Lakes, and the alewives were poised to finish the job.

Our lakes needed a hero. Enter Dr. Howard Tanner.

The Michigan Department of Conservation was desperate for a solution, so they tried a Hail Mary in the form of the Pacific chinook and coho salmon. The salmon feed on alewives, so they figured if they introduced a whole bunch of non-native salmon into the Great Lakes, it might do the trick.

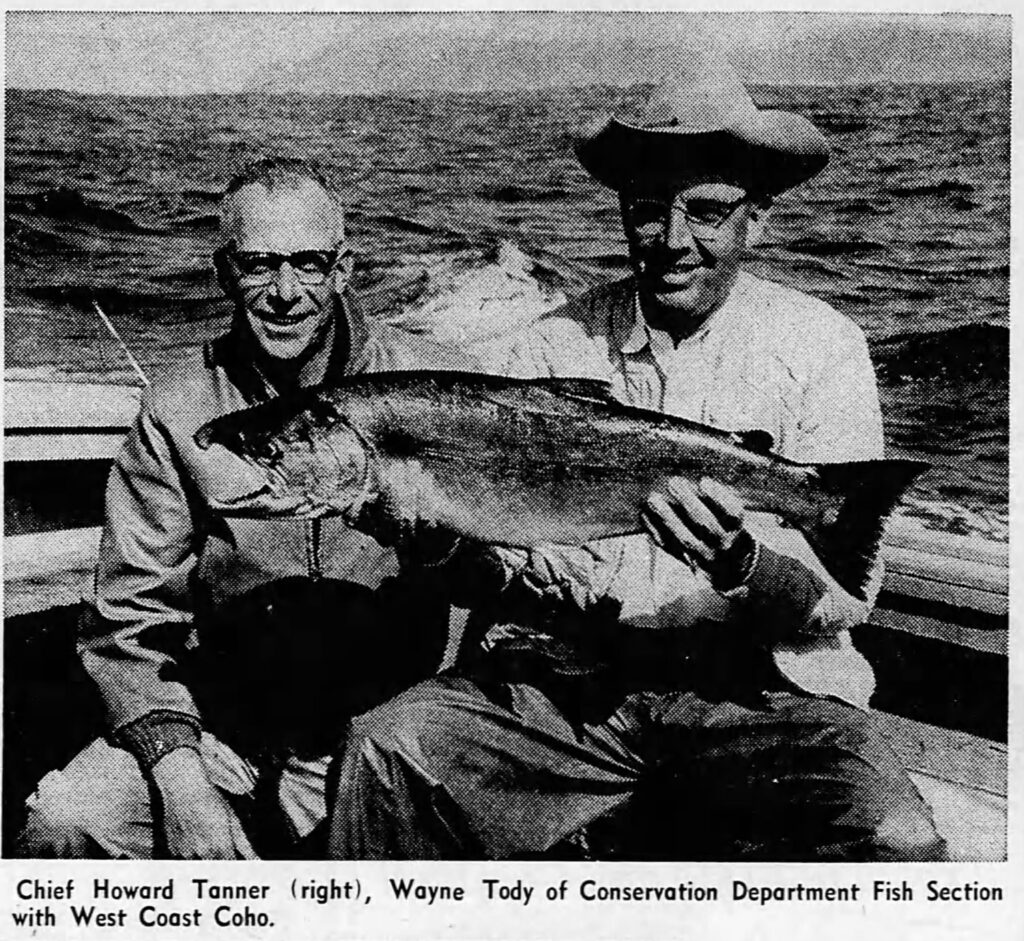

The salmon idea was the brainchild of Dr. Tanner, an aquatic biologist from Michigan State University, who had been hired as chief of the Michigan DNR Fisheries Division.

In 2019, the 95-year-old Tanner told his story to the Lansing State Journal. He recalled seeing a mass of dead alewives on the Lake Superior beach near Marquette that was seven miles long and a half-mile wide. “It was huge,” he said. That sight showed how urgent it was that we get rid of them.

He planned the first salmon release for April 2, 1966, and held a big press conference in Lansing to promote the plan. “We believe this coho salmon program has tremendous potential for Michigan fishing,” he said. “April 2 could well become a landmark date in state conservational history.”

It worked. In spring 1966, they planted 850,000 coho in Lake Michigan and the salmon started feasting on the alewives. As the alewife population went down, the salmon population boomed, which was great news for recreational fishermen in the Great Lakes. They loved all the delicious and valuable salmon they were now able to catch.

To this day, if you ever feast on Great Lakes salmon, raise a glass to the man who made your meal possible, Dr. Howard Tanner.

In any case, Michiganders now had a dilemma—we had to choose between salmon and the other game fish such as perch, walleye and lake trout. If we get rid of all the alewives, we’d be eliminating the main source of food for the salmon.

To this day, it’s a delicate balance that the Great Lakes states and Canada continue to navigate, with Michigan taking the lead. The alewife population in Lake Huron crashed in 2004, nearly eliminating the salmon in the lake. The DNR had been planting hundreds of thousands of baby salmon in the lake every year, so they backed off a bit to allow the alewife population to recover.

Native fish continue to ebb and flow as the alewife population fluctuates. The strategy seems to be that we want “just the right amount” of alewives in the lakes. Enough to keep the salmon thriving, but not too much to crowd out the other fish.

We occasionally see mass die-offs of alewives like we did in the 1960s—there was a huge one in 2022 on Lake Michigan—but it’s not nearly the problem it was back then.

As for Dr. Tanner, he celebrated his 100th birthday in 2023 and is still going strong as we speak. The Michigan DNR’s 57-foot research vessel, the R/V Tanner, is named in his honor.

Just as Dr. Vernon Applegate rid the Great Lakes of the sea lamprey, Dr. Howard Tanner took aim at the alewives.

Not all heroes wear capes. Some of them use biology.

Buddy Moorehouse teaches documentary filmmaking at Hillsdale College.