Iryna Zarutska, a 23-year old Ukrainian refugee, was stabbed to death in cold blood on a train in Charlotte, North Carolina. Her murderer, Decarlos Brown Jr., pulled a pocket knife from his coat, stabbed her in the neck, and walked off dripping in blood muttering, “I got that white girl, I got that white girl.”

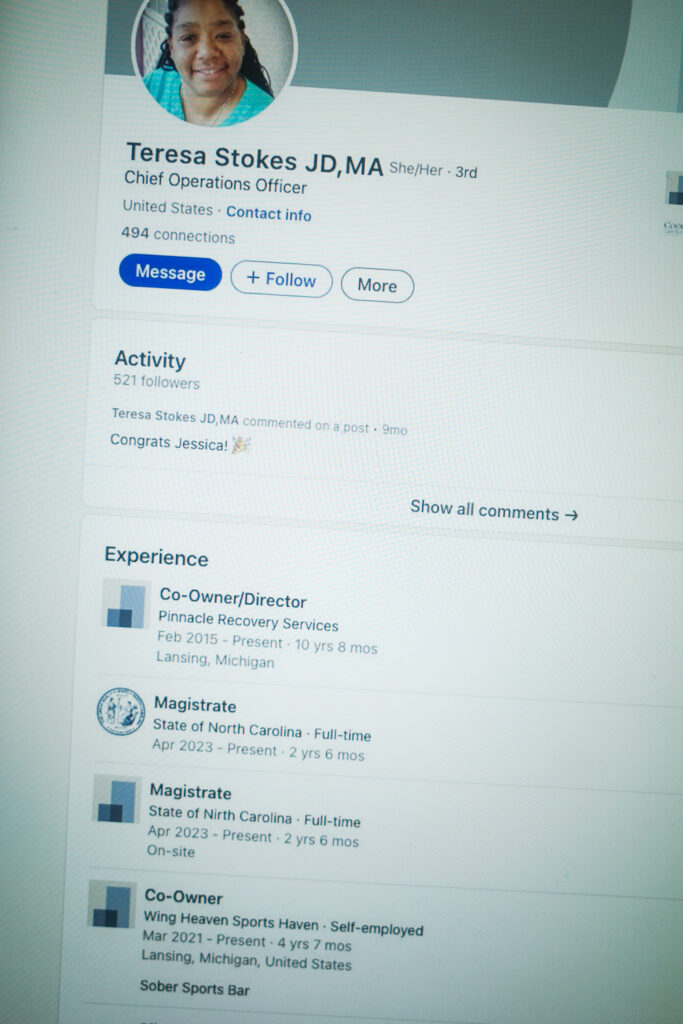

A judge who owns a Michigan addiction treatment center, Teresa Stokes, played a crucial role in releasing Brown from jail before this heinous attack. Digging into the judge’s history shows how pernicious judicial activists permit violent criminals to roam American streets for their own gain.

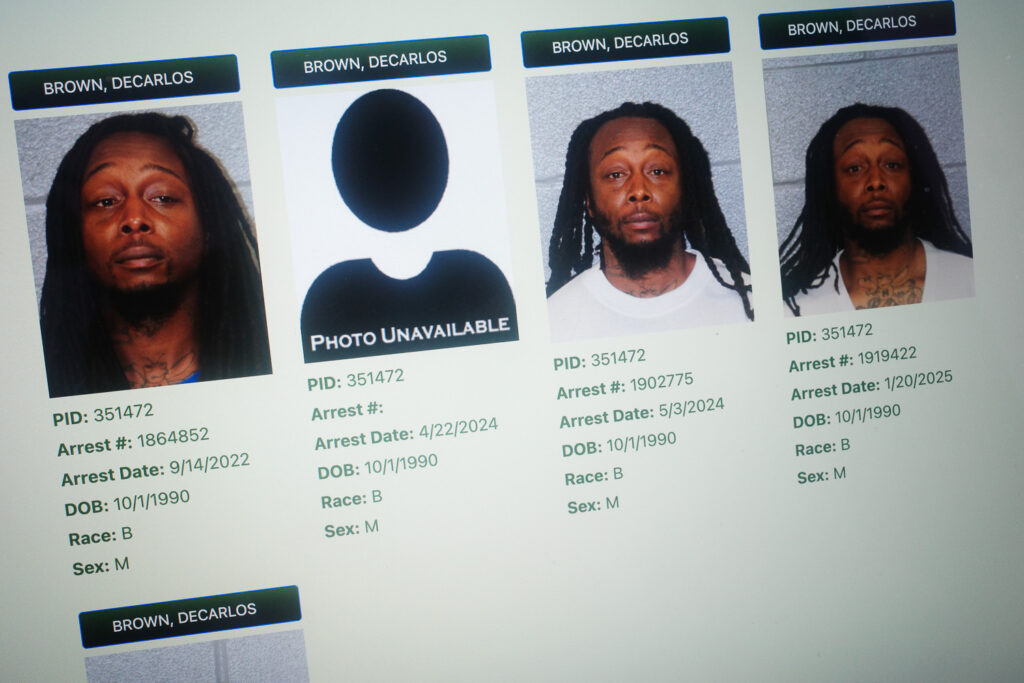

Brown, a repeat violent felon with a history of schizophrenia, was previously arrested 14 times. Felony larceny, breaking and entering, armed robbery, and assault are just a few of his criminal convictions.

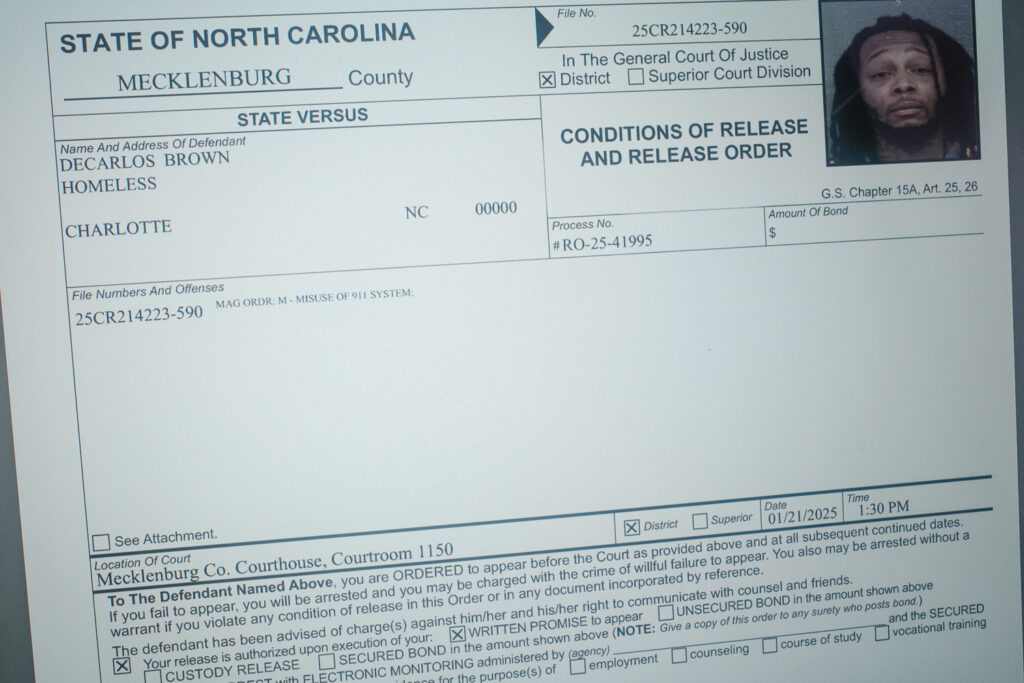

Recently, he was arrested three times over a series of weeks for misuse of the 911 system. In the first instance, he was acting erratically, the police were called, and he dialed 911 during their welfare check to complain of “man-made material” that he believed was inside his body, controlling him.

Following the third instance in January, he was arrested and released on the same day. In his court appearance, Magistrate Judge Stokes granted him cashless bail with only a written promise to appear at a later court date.

Six months later, a motion filed by his defense to evaluate his mental competency to stand trial was finally approved by a district court judge. He was mandated to check in to Alliance Health, a regional mental health center, but never appeared. A few weeks later, he murdered Iryna Zarutska.

Many online blame Judge Stokes, incredulous that a clearly mentally ill felon with a history of violence would be released back onto the street so casually. They’re right to do so—she is, in fact, perfectly emblematic of the institutional stupidity and corruption plaguing the judicial system.

In short, there are entire networks of activists, businesses, and judges that profit from keeping the drug and mental health crisis in our country in a state of managed decline. It’s far more lucrative, and professionally advantageous, to perpetually treat the symptoms, than to solve it for good.

You can trace Stokes’s career and see exactly how this insanity plays out.

Teresa first came to Michigan to attend Cooley Law School in Lansing, known as one of the worst in the country for its low job placement and bar exam pass rates. There are no records of Teresa herself ever passing the bar exam or practicing law in either Michigan or North Carolina.

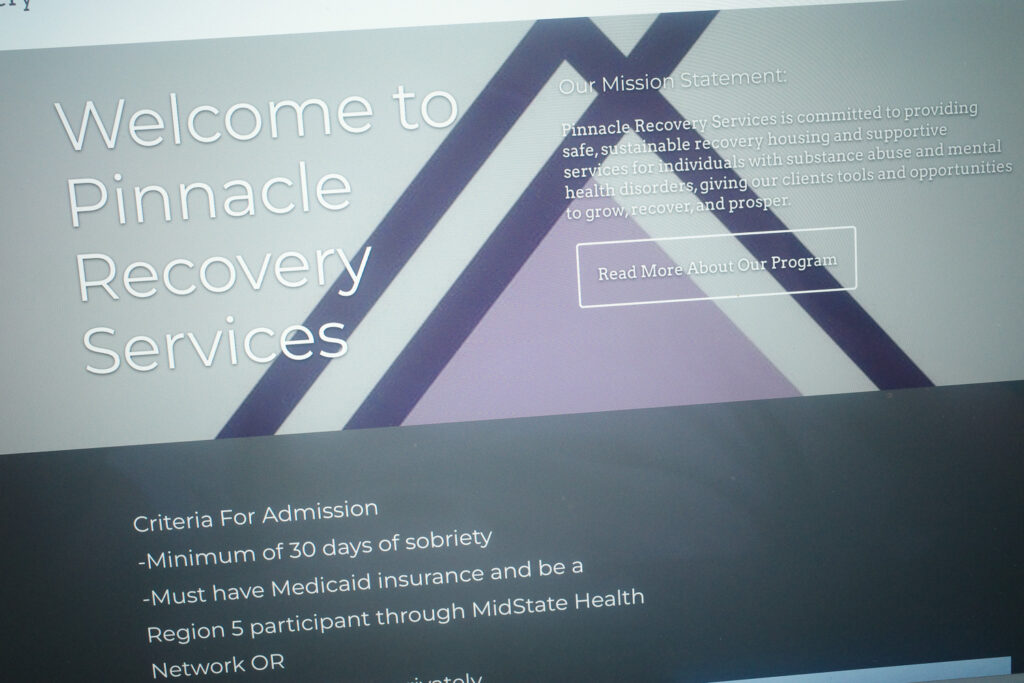

She opened a series of businesses in Lansing instead. She’s the co-owner and COO of Pinnacle Recovery Services, a residential treatment center for drug and alcohol addicts in Lansing. She also opened Wing Heaven Sports Haven, a “sober sports bar,” which shuttered in 2022.

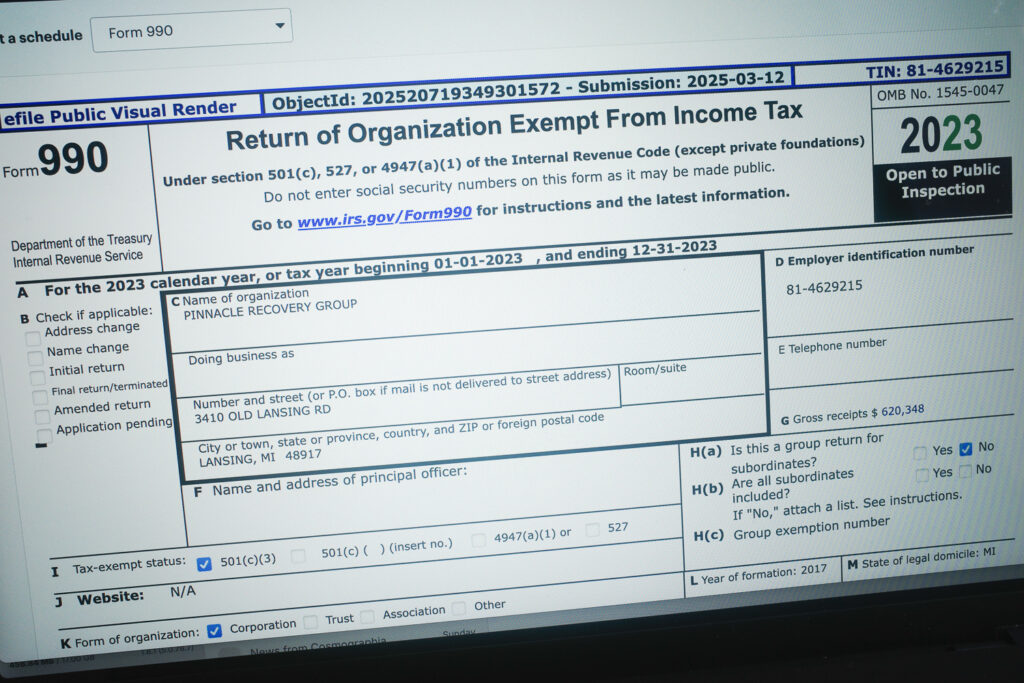

Businesses like Pinnacle are funded in large part by state and federal taxpayer money. Often registered as nonprofits, they avoid paying federal income tax and accept grants and donations. Pinnacle itself is registered as a 501(c)3 nonprofit corporation under the name Pinnacle Recovery Group.

Most of their funds come from the state Medicaid system and other block grants. Pinnacle itself bills through the Mid-State Health Network, a regional subcontractor for Michigan Medicaid that administers community mental health and addiction services for central Michigan.

This billing can be lucrative—Pinnacle says they have 26 beds available, and, according to the MSHN’s fee schedule, they could bill up to $136.50 per resident per day for low-intensive therapy and residence.

For 2023, Pinnacle’s 990 federal tax form reported $620,348 in gross receipts. A FOIA request filed by Michigan Enjoyer shows that $324,414.10 of that came from state Medicaid funds, doled out by the MSHN. The rest likely came from federal block grants.

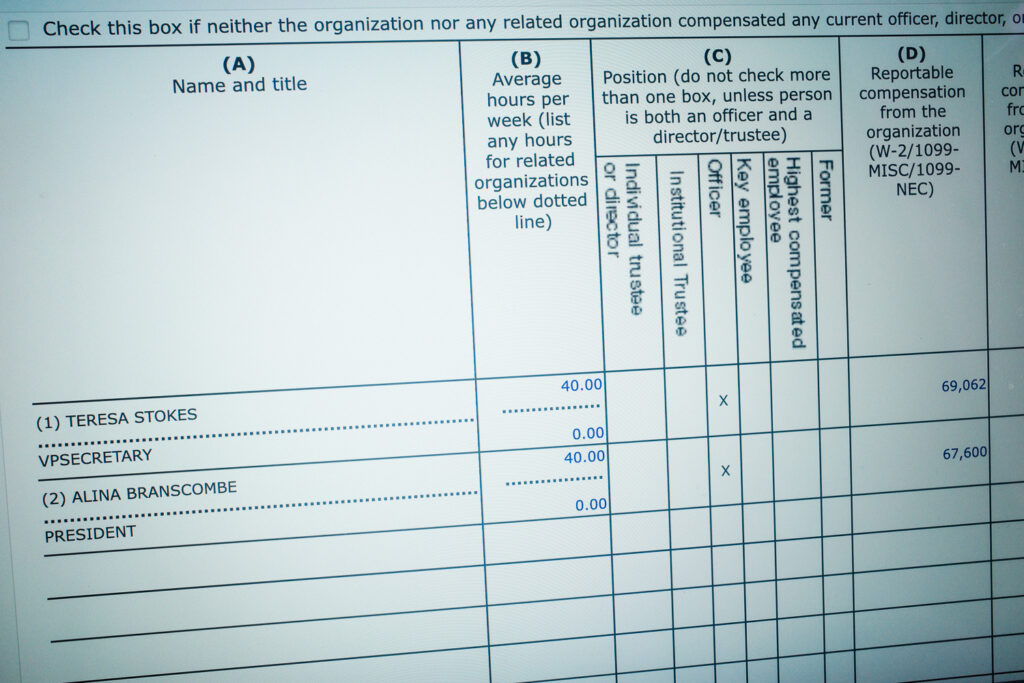

Teresa took home a 2023 W-2 salary of $69,062, roughly the same as her co-owner, despite serving as a Magistrate Judge in North Carolina since April of that year. Pinnacle’s federal tax filing still lists her as working 40 hours a week that year.

While these businesses operate as nonprofits, they’re able to skirt around the profit restrictions by paying out W-2 salaries to owners regardless of their work. Teresa is working as a judge in another state, for example, and clearly not working full-time at Pinnacle. Yet she still received more than 10% of gross billings as salary.

This sphere of businesses functions as an adjunct to the judicial system, funded by taxpayer money, with many residents sent there via court order. According to their own handbook, residents are not allowed to leave for weeks upon entering treatment, and strict rules govern their behavior.

How did Teresa become a magistrate in North Carolina? Turns out, the requirements are far less than you’d expect. You don’t even need a law degree to be appointed. Just a two-year degree and a few years in a “related field.”

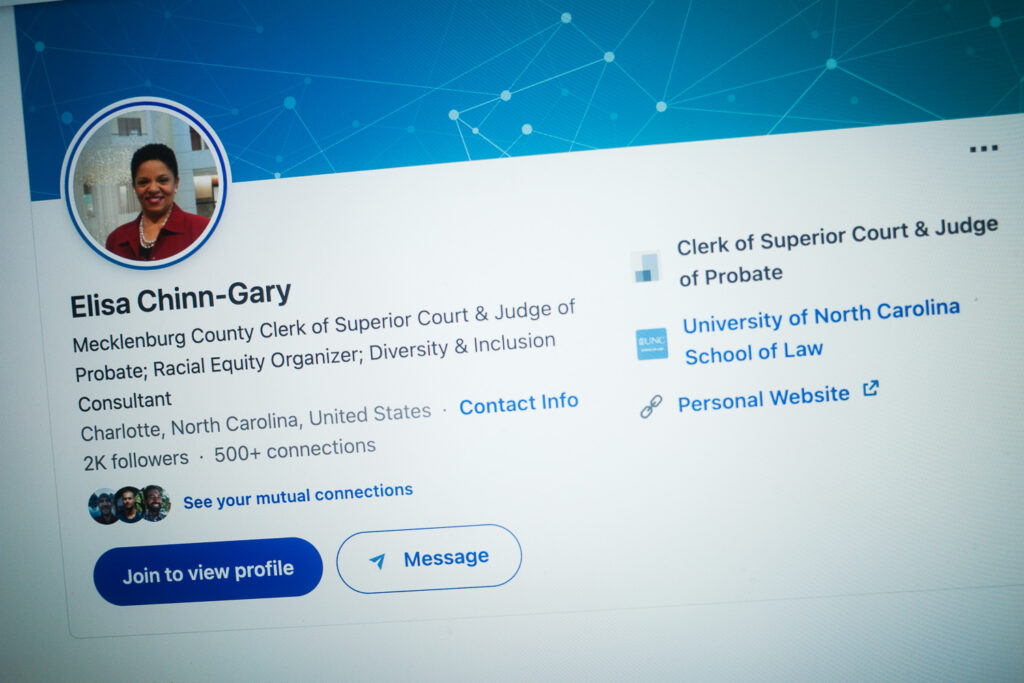

And, presumably, a connection. You don’t simply apply to be a judge on Indeed, you have to be appointed. Teresa was nominated by Mecklenburg County Clerk of Superior Court Elisa Chinn-Gary and confirmed by Chief Superior Court Judge Carla Archie.

These two women have ties to various racial and judicial activist groups in North Carolina, and it’s reasonable to think that their paths crossed here in some way. Teresa herself was a regular attendee, according to Pinnacle’s Facebook page, at Unite to Face Addiction – Michigan rallies in Lansing.

UFAM lobbies to “end the stigma” of drug addiction and increase funding for addiction treatment centers like Pinnacle. The nonprofit sphere is a small world, and there’s considerable overlap between activism for drug addiction treatment and the racial justice sphere.

Quite simply, they appointed one of their own—a fellow liberal black woman who shares their ideological convictions. The DEI industrial complex is really just another form of nepotism.

From there, the scheme is simple enough. Activist judges push for cashless bail, minimum sentencing, early release, but tack on parole and mandatory drug-addiction and mental-health treatment. And guess who owns the treatment facilities?

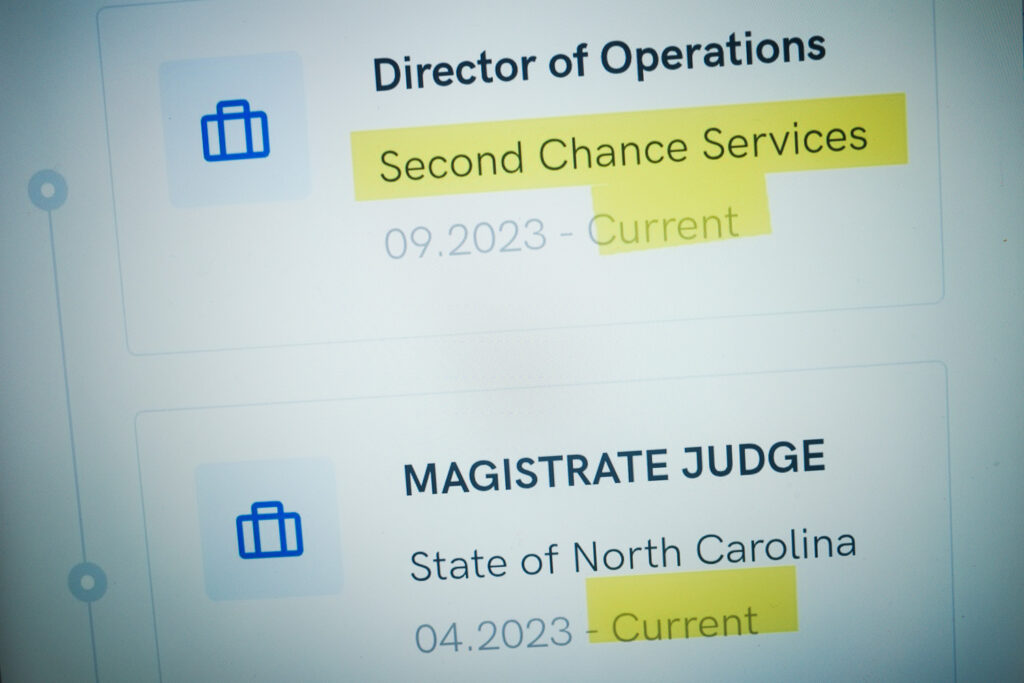

Stokes is also listed as the director of operations at Second Chance Services, a Charlotte-based addiction treatment facility similar to her business in Lansing. Presumably, she’s collecting a salary here as well, alongside her paychecks from Pinnacle and her work as a magistrate.

Of course, as a magistrate judge, Stokes is directly responsible for releasing drug addicts and severely mentally-ill felons back onto the street without bail, or ordering them into treatment facilities like the ones she owns and works at, on the taxpayer dime.

Is it corruption, naive stupidity, or both?

Usually, it’s both. The thing is activists like Stokes really do think that abolishing bail, lowering sentences, and increasing funding for privately run community treatment centers is the solution to societal woes.

They do, however, conveniently benefit from all of this.

Keeping these violent felons in the revolving door of a feckless court system makes for busy judicial work, more magistrate appointments for friends, more awards for diversity initiatives to list on their LinkedIn profiles.

For the nonprofit sphere, and the for-profit treatment centers, all of their funding rests on there being a constant state of barely managed crisis. They make money directly from it, in fact, and without the societal woes of addiction, mental illness, and violent crime, they’d be out of a job.

Clearly, drug addiction and severe mental illness, particularly when paired with violent crime, need to be treated. But this model of treatment, run by toothless private businesses growing fat off public money, backed by activist judges pushing criminals out of the prison system and into their hands, is directly harming society.

It allows individuals like Decarlos Brown Jr. to commit repeated violent crimes, exist in a state of demonstrable psychosis in public, and murder an innocent 23-year old woman.

It has its faults, no doubt, but there’s one good thing about the prison system. It keeps people like Brown away from society. When it comes to mental-health crises, severe drug addiction, and especially violent crime, this can be the only answer. State institutionalization, removal from society until fit to return, or permanent removal if the person is a threat to others.

If we keep allowing judicial activists to undermine this system for their own gain, we’ll keep seeing tragedies like this over and over.

We don’t have to live like this—we choose to.

Bobby Mars is art director of Michigan Enjoyer. Follow him on X @bobby_on_mars.