Detroit — Mike Duggan’s final State of the City address as Detroit’s mayor was a dress rehearsal for governor.

Without making a direct comparison, Duggan painted a contrasting picture with Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s vision of the Michigan economy.

It was the difference between greenfields and brownfields. And it was the difference between cash handouts and tax cuts. As Duggan looks to separate himself from the Democrat Party he abandoned after the 2024 election, his economic plan is a smart point of departure.

“Who wants all this farmland chewed up with new development?” Duggan asked the crowd at the new Hudson’s Building in downtown Detroit.

“What brownfield means is, instead of building out in a green field and chewing up farmland, you take an older site and you give a discount to reinvest there,” Duggan said.

This was a reference to brownfield tax credits, which reward redevelopment. Duggan believes this a smarter approach than turning green land into developed land.

A strong and viable Detroit is in everybody’s interest in Michigan. Detroit gives the young professionals of Michigan someplace to live close to home. They can stay a short car ride away instead of moving to Chicago. If you’d like to enjoy your grandkids, and not just visit with them, you should be rooting for Detroit.

Compare this to the big projects of Whitmer’s term, like when Gotion, a Chinese EV battery company, tried to elbow its way into Big Rapids. All it did was alienate the many neighbors it couldn’t buy out.

And when Ford created BlueOval Battery Park to build EV batteries, why did it go to Marshall? In both cases, companies skipped past a place that could use the jobs—Detroit—for a heartland where they are not wanted or welcome.

If Duggan can assure people that brownfields will be redeveloped before greenfields are touched, that would make a lot of sense.

Without attacking anyone for it, Duggan spoke against the corporate welfare consensus in Michigan, where political leaders try to attract big firms by cutting big checks. This has been commonplace since the Granholm administration. Snyder continued down that path, rather than stop it. Whitmer ramped corporate welfare up to levels not before seen.

That’s not the mayor’s plan if he becomes governor.

“In Detroit, we don’t front money,” Duggan claimed.

Corporate welfare does not create jobs, but it creates headlines for politicians. Granholm, Snyder, and Whitmer have all played headline games with taxpayer money. Win or lose, Duggan’s influence has the chance to move the corporate welfare outside the Overton Window in Lansing.

When Ford bought and rehabbed the Michigan Central train station, Detroit figured out that if it paid 30 years of fair-market taxes, it would owe $400 million. It gave Ford a 25% discount.

Duggan said he’s criticized for “giving Ford $100 million.” But it’s better understood as taking in $300 million that the city never would’ve seen if the land remained fallow.

Since Duggan announced his candidacy for governor, but said he was leaving the Democrat Party and running as an independent, it’s been an open question: Is Duggan crazy like a fox, or too clever by half?

As an independent, Duggan is the only candidate we know who will make the November 2026 ballot. That’s clever.

But straight-ticket voting is an ingrained habit in Michigan. That’s what makes it not so clever.

A different kind of Democrat? That could work. But a reinvention of the wheel sounds unlikely. Duggan made lightning strike once in 2013, when he won the Detroit mayoral primary with a write-in campaign. But Detroit was a poor city thirsting for leadership, and Duggan was a successful CEO.

Detroit and Duggan needed each other in 2013 a lot more than Michigan and Duggan need each other in 2026.

That’s what makes his timing and decision-making look funny in the light.

Had Duggan stayed in the Democrat Party, he might be the consensus favorite, given Benson’s stumble start and lack of charisma.

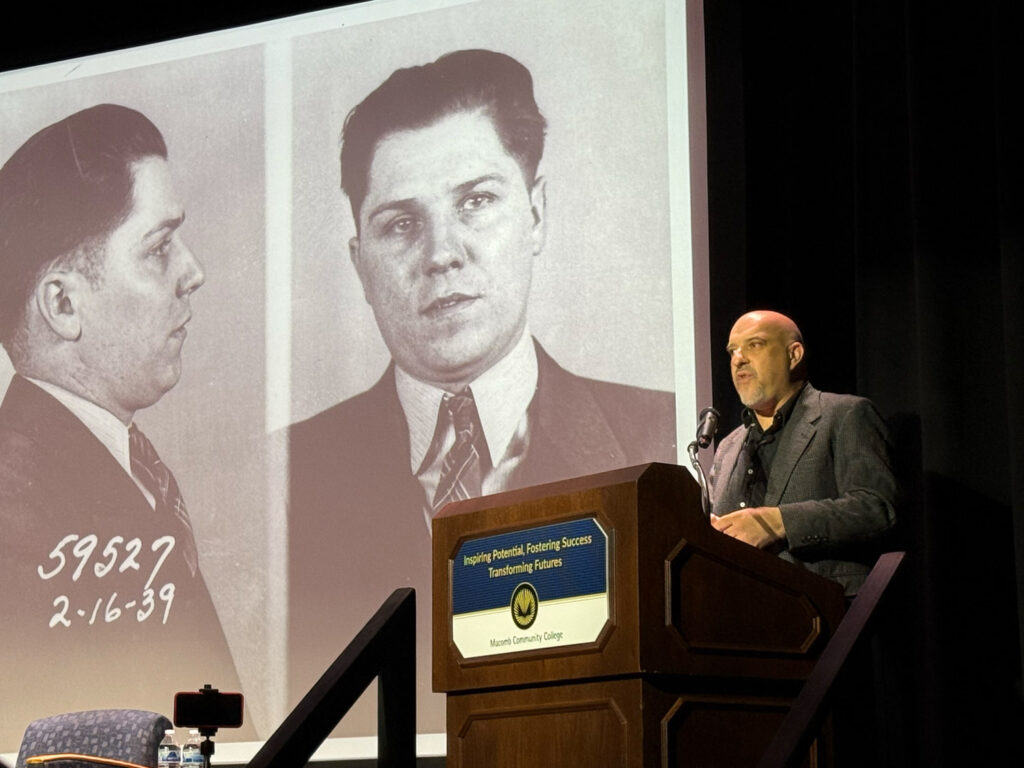

When Duggan worked the clicker in front of a room of Detroit VIPs, he looked every bit like a chief executive who’d been there before. Benson could never.

Duggan didn’t just show a lack of loyalty in ditching the Democrats. He showed a lack of faith in himself to lead them to a better place.

Duggan is going out of his way to not attack anyone and to paint attacks as an example of the bad, old way of doing politics. It sounds good, until millions of dollars of ads run against him from morning till night. In that cacophony, neither the people nor the gods can hear cries for civility.

Duggan looked at Detroit in the throes of a bankruptcy and said, “Sign me up!” Duggan looked at the Democrats after they lost one election and fled.

Where did the confidence go?

Duggan didn’t see himself as part of the solution, the way Bill Clinton was for the Democrats in 1992.

Why, then, does he think he can fix Michigan?

James David Dickson is host of the Enjoyer Podcast. Join him in conversation on X @downi75.