When the first Winter Olympics took place 102 years ago in Chamonix, France, the U.S. flag was carried in the opening ceremonies by a big, bruising hockey player from Sault Ste. Marie named Clarence “Taffy” Abel.

He was one of the greatest hockey players in the world and a stone-cold Yooper legend. Years later, the world found out that in addition the U.S. flag, he was also carrying a huge secret with him.

As the 2026 Winter Olympics kick off in Italy, it’s a great time for all Michigan sports fans to know the story of the great Taffy Abel, who was known as “The Michigan Mountain” in his playing days and who proudly represented his country in the 1924 Games.

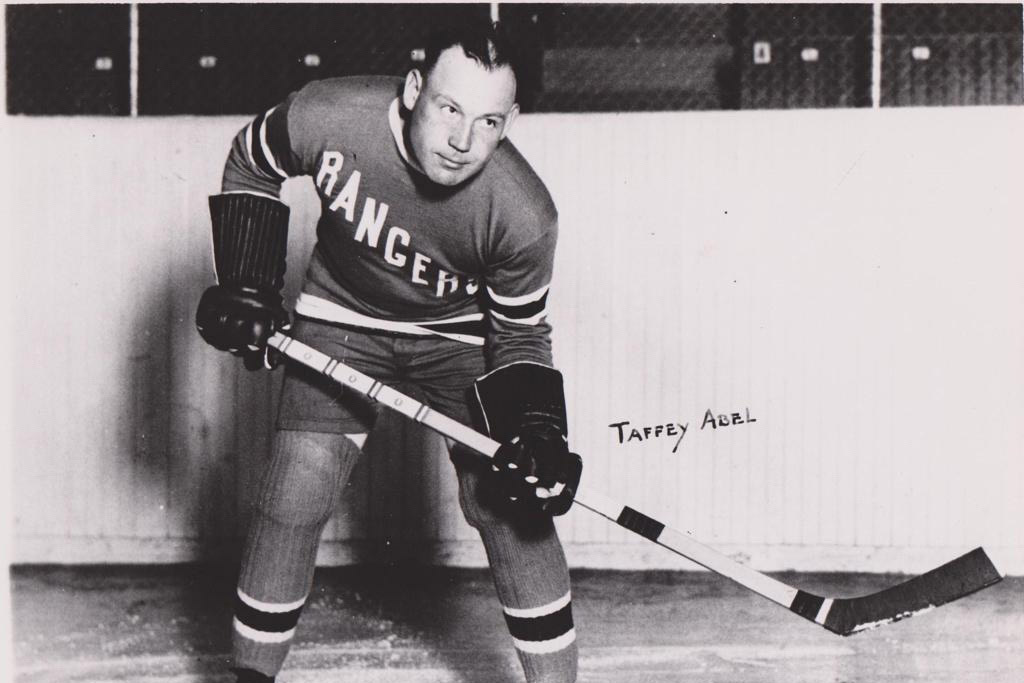

Taffy won a silver medal in those Olympics (more on that in a minute) and went on to have a long career as the first American-born player in the National Hockey League, winning a Stanley Cup with both the New York Rangers and Chicago Black Hawks.

The secret that came out long after his playing days ended was this: Taffy Abel was a Native American. He was a member of the Ojibwe Sault Ste. Marie tribe on his mother’s side, but his parents hid that fact when he was a child because they didn’t want Taffy and his sister to be forcibly sent to an Indian Boarding School.

When Taffy became an adult, he continued to hide his heritage, because he didn’t want to endure the discrimination that many Native Americans faced. The truth didn’t come out until his mother passed away in 1939.

These days, Taffy Abel is celebrated as not only the first American-born player in the NHL but also the first Native American. And he’s still the only Native American who has ever carried the flag for the U.S. in any Olympics.

His story begins in the Soo in 1900, when Clarence was born to John Abel, a white man, and Charlotte Gurnoe Abel, whose father was a full-blooded member of the Chippewa tribe in Sault Ste. Marie, also called the Ojibwe. He picked up the nickname “Taffy” because he was always slipping a piece of the candy in his mouth when no one was looking.

His parents made the decision early on to hide the fact that Taffy and his younger sister Gertrude were Native American, because they didn’t want them sent away to a boarding school, and no one in the Soo dug into the matter.

Hockey was king in the Soo, and Taffy started playing as a kid. His unique combination of skill and size made him stand out right away. He grew to be 6-foot-1 and 225 pounds, massive for a hockey player back then.

A bruising defenseman, he played during his teenage years for the Sault Wildcats, a member of the United States Amateur Hockey Association. He caught the attention of William S. Haddock, the president of the association and the man charged with putting together the U.S. Olympic Hockey Team for the upcoming 1924 Winter Olympics in Chamonix, France—the first Winter Olympiad.

Haddock invited the Michigan Mountain to join the Olympic team, and, in early January that year, Taffy joined the rest of the Olympians on board the luxurious USS James A. Garfield for the trip across the Atlantic. Before taking off, the U.S. hockey team played in a few exhibitions against a team from Boston, and the Olympians got their clocks cleaned.

Taffy wrote a letter back to his hometown newspaper, the Soo Evening News, when he got to France.

“It looks to be a certainty that we’ll meet the Canadians in the finals, but we must develop teamwork,” he wrote. “We have surely got to show more than we did in Boston, where we looked terrible. If we play that way against Canada, they will need an adding machine to keep track of their scores.”

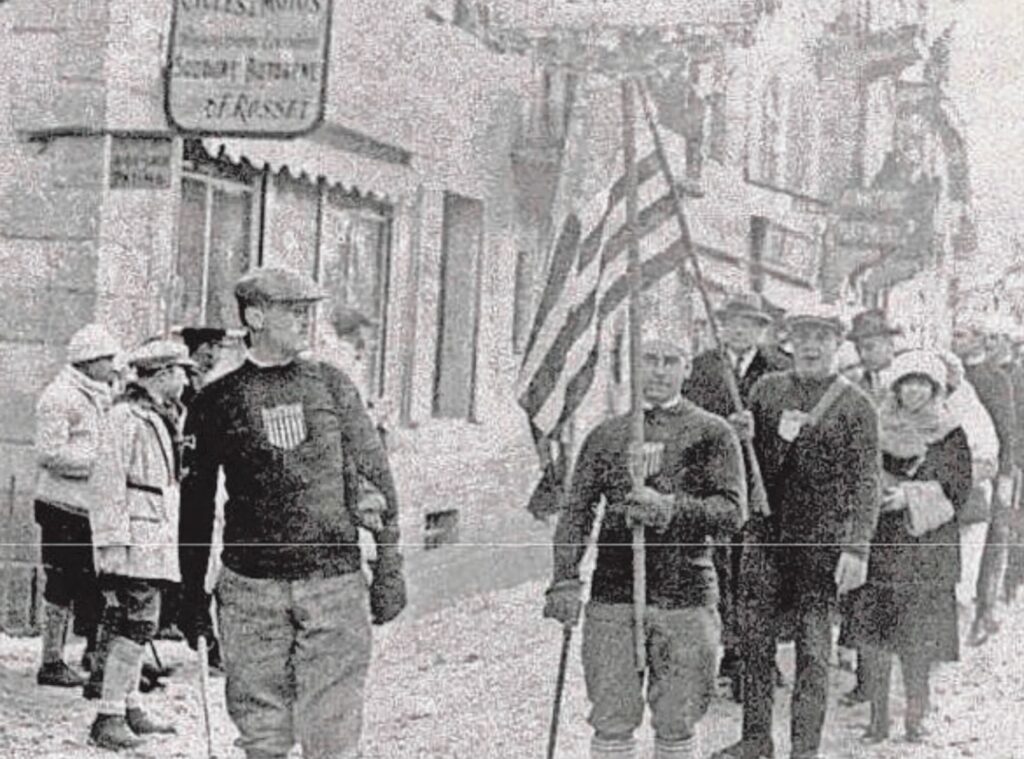

The Winter Olympics began on Jan. 25 with the opening ceremonies, which were basically just a parade of nations through the streets of Chamonix. All the athletes carried their hockey sticks or curling brooms or skis with them. The bobsled guys were pulled through the streets on their bobsleds.

Then as now, every nation’s contingent was led by one of the athletes carrying their country’s flag. The U.S. team only had 24 athletes (22 men and two women), and, since the hockey team made up the bulk of the team, they decided to let the hockey players pick the flag-bearer.

They picked our Taffy Abel, the biggest player on the team and its spiritual leader. Taffy proudly carried the Stars and Stripes through the streets of Chamonix as he led the Americans.

The Olympic hockey tournament in 1924 looked nothing like it does now. There were only nine members on the U.S. team—seven skaters and two goalies—and the players on the ice rarely came off. As the team’s best defenseman, Taffy Abel played almost every minute of every game.

And while big games in the U.S. and Canada back then were always played in indoor arenas, the Olympic tournament in Chamonix was played on a natural outdoor rink with no boards, with the beautiful French Alps in the background. It was basically a glorified game of pond hockey.

There were eight teams in the Olympic tournament that year—the two North American teams and six teams from Europe—but the European teams were terrible. The U.S. won its three round-robin games by scores of 19-0 (against Belgium), 22-0 (France), and 11-0 (Great Britain). Taffy scored 15 of those goals. Canada beat the hell out of Czechoslovakia, Sweden, and Switzerland by a combined score of 85-0.

The Canadian team wasn’t an all-star team of Canadians, either. It was just an amateur team from Ontario called the Toronto Granites, but they were good.

The round-robin results set up the predicted gold medal match of the U.S. vs. Canada, which was played under sunny skies in Chamonix on Feb. 3, 1924. Taffy and the Americans hung tough in the first period, trailing just 2-1 on a goal by forward Herb Drury of Pennsylvania, but Canada took over in the second and third periods, winning the game and the gold, 6-1.

Taffy came home to the Soo with his silver medal and was treated like a hero. He resumed his season playing for a team in St. Paul, Minnesota, and two years later, in 1926, he made his debut as the first American-born player in the NHL.

Taffy lasted eight seasons in the NHL, winning the Stanley Cup with both the Rangers and Chicago Blackhawks, and scored 19 career goals. The Michigan Mountain also racked up 359 career penalty minutes, distinguishing himself as sort of the Bob Probert of his time.

Taffy spent the rest of his days in Sault Ste. Marie, and he was every bit the Yooper legend. He owned a steakhouse in the Soo called Taffy Abel’s Supper Club, and the big man tended bar every night. He would regale everyone who came in with tales of the Olympics and the NHL.

In 1939, when his beloved mother Charlotte died, Taffy also quietly revealed the secret that he’d been keeping his whole life: He was an Ojibwe. He later started a semi-pro team called the Soo Indians—a nod to his heritage —serving as its coach.

Taffy passed away in 1964 at the age of 64. He and his wife Irene didn’t have any children, but he had an entire peninsula mourning his passing.

Herb Levin, the sports editor of his hometown Soo Evening News, eulogized him by saying, “Taffy looms in the imagination of old-timers as a sort of superman with skates.”

To ensure that his legacy would never be forgotten in the Soo, Lake Superior State University made the outstanding decision a few years later to name its hockey stadium the “Taffy Abel Arena.” The LSSU Lakers have won three national championships in that arena, paying proper homage to the Michigan Mountain.

It’s been 102 years since Taffy Abel carried the flag for his country in Chamonix, and, as a new Winter Olympics begins in Italy, there are eight athletes from Michigan who will be playing for the U.S. hockey teams (six men and two women).

Here’s hoping they point to the skies before the first puck drops and give props to the Yooper who started it all. All hail the great Taffy Abel.

Buddy Moorehouse teaches documentary filmmaking at Hillsdale College.