The disappearance of Amelia Earhart is one of the greatest mysteries in American history.

The pioneering 39-year-old aviator from Kansas disappeared somewhere over the Pacific Ocean on July 2, 1937, as she was attempting to become the first female pilot to circumnavigate the globe. To this day, searchers work to locate her plane and find out what happened to her and her navigator, Fred Noonan.

Thirty years to the day after Amelia Earhart embarked on her unsuccessful flight, a female pilot from Michigan successfully completed it for her.

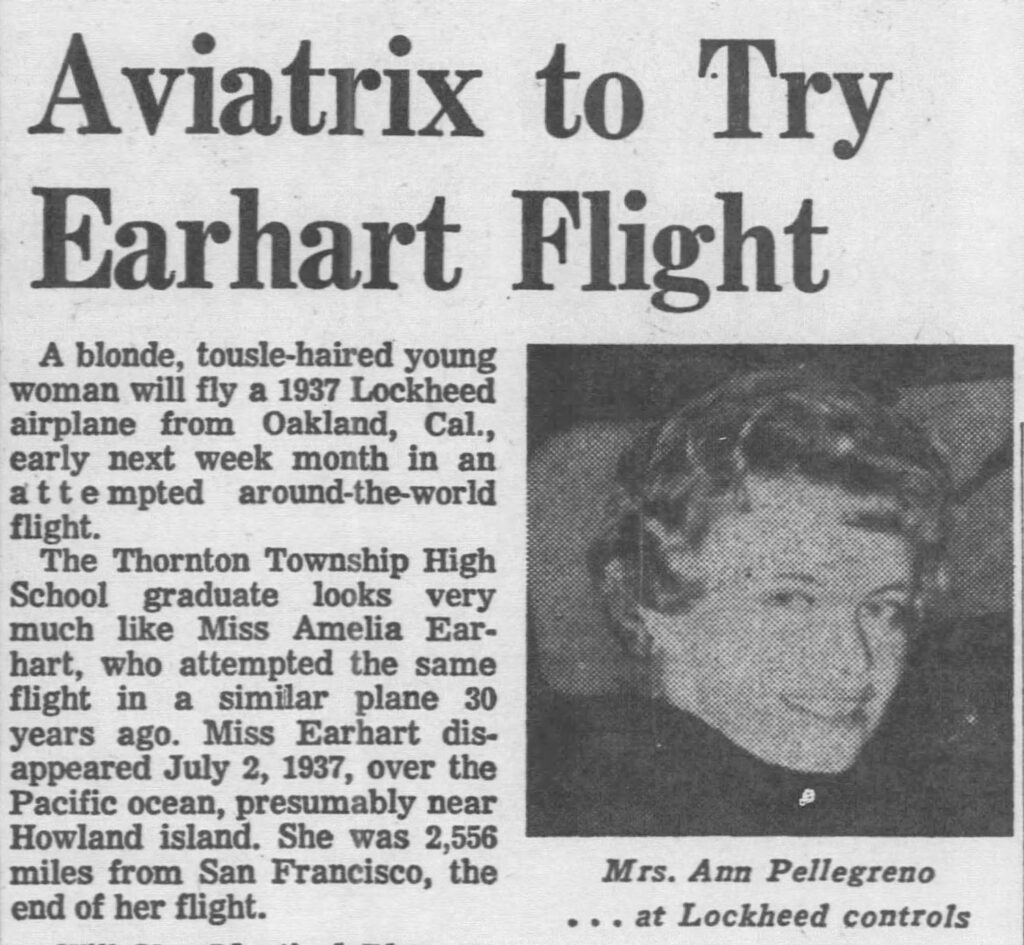

Ann Pellegreno was her name, and in the summer of 1967, she flew the exact same route that Earhart did in the same type of plane on the same dates and with most of the same refueling stops.

It was dubbed the “Amelia Earhart Commemorative Flight,” and Pellegreno did it to honor her idol. When she returned, she was hailed as an international hero and honored with a huge parade in her hometown of Saline.

Pellegreno had less than 1,000 hours of flight experience when she began the trip. Pellegreno, who is now 87 years old and lives in Texas, continues to speak about the flight that made her famous.

“I would say (to Earhart) that I truly believe you were there when I made my flight,” she said in 2023.

Pellegreno was born in 1937, the year of Earhart’s ill-fated flight, and grew up in Chicago. She moved to Ann Arbor to attend the University of Michigan, where she majored in music and graduated in 1958. She met her husband, Don, in the U-M Concert Band and took a job as an English teacher at Saline Junior High School after graduation.

She caught the flying bug in 1961 and earned her private pilot’s license. In 1966, she earned her commercial pilot’s license and gave up teaching to become a full-time pilot.

About that time, she met an aircraft mechanic from Ypsilanti named Leo Koepke who had recently purchased and restored a 1937 Lockheed 10 Electra, the same plane Earhart had flown.

It was Koepke who put the bug in Pellegreno’s ear: You need to complete Amelia Earhart’s flight for her.

It took some convincing, but Pellegreno eventually agreed to try. Unlike Earhart, who had started the trip with only one navigator on her crew, Pellegreno decided she needed three other crew members. Koepke would serve as the mechanic, William Polhemus of Ann Arbor would be her navigator, and an Air Force colonel from Virginia named William Payne would serve as her copilot.

The stars were aligned, and Pellegreno decided that she would start the trip 30 years to the day after Earhart started her flight—June 9, 1967—and take off from the very same airport in Oakland, California.

Pellegreno was 30 years old, nearly a decade younger than Earhart. Reporters at the time noted that Pellegreno also bore a striking resemblance to her idol. “She looked enough like Earhart that she could be her daughter,” one reporter wrote.

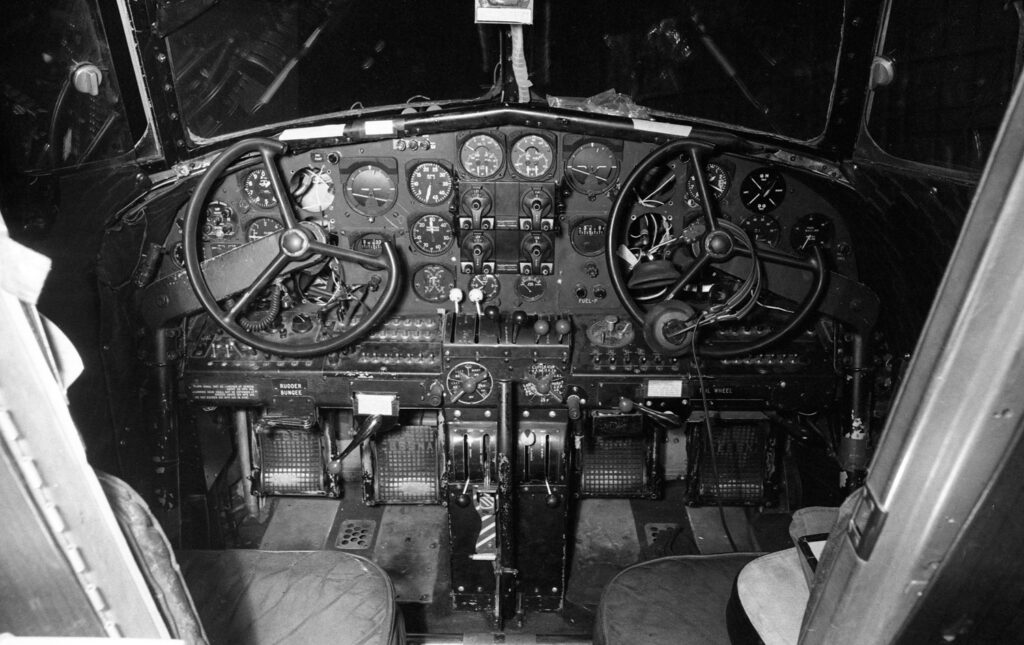

Pellegreno’s crew had several technical advantages over Earhart and Noonan, including much better navigational tools, but the inside of the plane was just as spartan and bare as Earhart’s. It was anything but luxurious, and, considering they were going to be spending 10 hours a day inside it for a month straight, that was an issue.

Pellegreno and her crew took off on June 9 heading east, making refueling stops in Tucson, Fort Worth, New Orleans, and Miami before heading across the ocean to Puerto Rico. The Lockheed 10 Electra was a tremendous gas guzzler, going through 50 gallons an hour, while flying no faster than 150 mph. The fuel for the trip alone cost $10,000 (nearly $95,000 in today’s dollars).

The flight was incredibly tedious, but thanks to their meticulous planning and attention to maintenance, there were almost no issues along the way. Except one: Pellegreno suffered a terrible case of dysentery midway through the trip and had to spend two days lying on the air mattress in the cabin while her copilot took the controls.

The trip covered a whopping 28,000 miles, including 10,000 miles over water. They made 30 stops in all during the trip, including in Venezuela, Trinidad, Brazil, Senegal, the Canary Islands, Portugal, Rome, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, India, Indonesia, and Australia.

On July 2, she landed in Lae, New Guinea, the last stop Earhart made before she disappeared. That’s where the trip got truly emotional for Pellegreno.

“I met some people who had seen Amelia take off from the same airport 30 years earlier,” she said.

This was also by far the most crucial part of the trip, because she wanted to locate Howland Island, the unoccupied strip of land in the middle of the Pacific that Earhart was searching for when she disappeared. The U.S. military had built a tiny airstrip for Earhart to use as a refueling stop, but she never made it there.

Pellegreno wanted to find the island not just because that would have truly marked a “completion” of Earhart’s flight, but also because she wanted to leave a wreath there in her idol’s memory.

When they got close to where they thought Howland Island should be, they couldn’t find it. They were circling the area when rain showers began, and they couldn’t see Howland Island anywhere.

“It was easy to imagine what Earhart and Noonan must have felt 30 years ago,” she said.

Then the clouds parted just a bit, and it appeared.

“We’d been within 10 miles of it for about 20 minutes,” Pellegreno said. “We wondered how close the other two had come and never saw it.”

They thought about trying to land on the island, but Pellegreno quickly noticed that the airstrip was no longer visible. So she took the plane down as low as she could and dropped the wreath out.

Five days and a few stops later, she returned to Oakland on July 7. The 30-year-old pilot from Saline had done it.

Pellegreno got a huge reception in Oakland when she landed and an even bigger one a couple days later in Kansas, where she stopped in Amelia Earhart’s hometown on the way back to Michigan.

She eventually landed the plane for the last time at Willow Run Airport in Ypsilanti and was thrilled to be back home. “I just want to sit down on something that isn’t moving,” she said.

The people in Saline greeted her with a huge parade down Michigan Avenue.

Pellegreno and her husband moved to Iowa a few years later and eventually ended up in Texas, and she has spent the last 58 years giving speeches and writing books and telling anyone who wants to hear the story.

To this day, people continue to ask her what she believes happened to Amelia Earhart. Was she captured by the Japanese? Did she die as a castaway on some other remote island? Did she actually make it back to the U.S. and change her name to avoid publicity?

Pellegreno’s theory is far less exotic. “I feel she ran out of gas and went down somewhere,” she said.

That might be the accepted theory, but it hasn’t stopped people from looking for her.

This summer, an archeologist from Oregon named Dr. Richard Pettigrew will lead a crew of 10 people on an expedition to a remote island called Nikumaroro, where he believes the plane crashed. He hopes to find the plane and maybe even the skeletal remains of its two passengers.

The legend of Amelia Earhart lives on. And so does the legacy of Ann Pellegreno.

Buddy Moorehouse teaches documentary filmmaking at Hillsdale College.