On Christmas Day 1965 in Muskegon, Sherman Poppen watched his children open up a toy that would change everything.

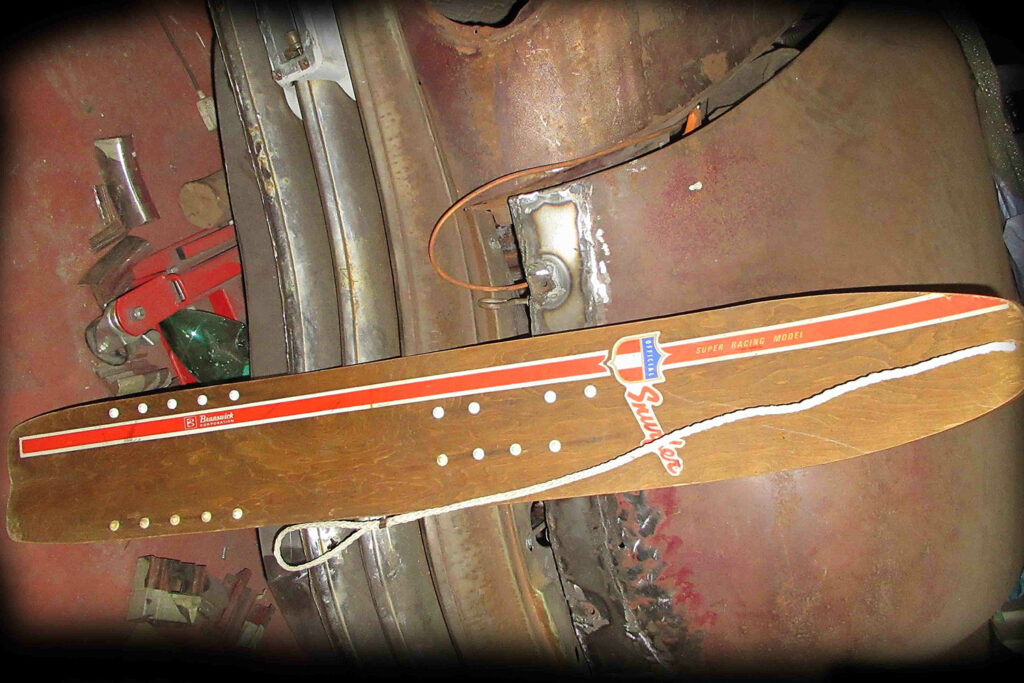

His invention, named by his wife Nancy, was called the “Snurfer,” a contraction of snow and surf. It was a wide wooden board made of two skis braced together without foot bindings, wide like a surfboard. Shortly after crafting it in his garage, he received a suggestion from his father to add a rope to the front for a better ride.

Family and friends immediately loved it, and he knew he had built something substantial.

“When I saw how much fun the kids had Christmas Day, I spent the next week in Goodwill and everywhere else, buying up every water ski I could find,” Poppen said. While it wasn’t exactly the first of its kind, he was the first to sell his product, patenting it a year after its invention.

Just a few years later, more than 300 people came to the first World Snurfing Championships at Muskegon’s State Park, with Ted Slater and Sally Waite winning the competition.

Brunswick Corp., Poppen’s equipment manufacturer, turned out to not understand how to market this new craze. To the degree that the Harvard School of Business now uses the Snurfer as an example on how not to market a product. They had solely focused on the novelty of the board, not its sporting potential. Yet its popularity was still undeniable, and they sold nearly a million boards by 1970.

A few years down the line, the Snurfer was revamped as a racing machine. But the damage had already been done. By the end of the 1970s, the public still viewed the board as a novel toy.

While Poppen’s company had its ups and downs, some of the kids still riding got pretty good at it. Doing tricks like 360s and front flips, a man named Paul Graves became a Snurfing champion in Muskegon by proving that the toy could shred.

That’s where it garnered the attention of Jake Burton Carpenter, who saw Graves showcasing the Snurfer’s potential at an event they both were competing in. Burton went on to develop his own improved boards.

Poppen had begun to lose control of the very market he had created. Derivatives of his product were popping up everywhere. He fought back by enforcing his Snurfer trademark, and Burton was forced to rename his boards. The name he chose? Snowboards.

In 1982, Graves, the first sponsored Snurfer rider, organized the first National Snurfing Championships held outside of Muskegon. This time they were in in Vermont. The event was renamed the National Snow Surfing Championships.

After the success of the championship, Burton took over from Graves and renamed the event the U.S. Open Snowboarding Championship. As Burton further pivoted to sell his snowboards as a lifestyle rather than just a sport, Poppen struggled to find a licensing deal for his own product. The Muskegon National Snurfing Championship closed due to a lack of competitors while snowboarding began its steady climb to stardom, becoming an Olympic sport by 1998.

In the past few decades, there has been a resurgence in snowboarders who want a more classic and challenging experience, found by riding without foot bindings. Thanks to this organic desire from riders, a manufacturer was making the classic Snurfer again by 2014. This resurfacing has led others to produce similar “snow surfers,” such as Burton’s own “The Throwback.”

Before his passing, Poppens said in an interview, “I am deeply in John Burton Carpenter’s debt for what he did. ‘Cause he took it all the way.”

Understanding the current state of Snurfer started with finding a board.

Trying to get my hands on a Snurfer seemed simple enough. A quick call to a Muskegon ski shop seemed like a good place to start. The employee explained that Snurfer stopped selling boards to dealers about a year ago, but that you can order one online.

Clearly sales were good. Their boards online were mostly sold out. I looked up the Snurfer corporate number instead and gave it a go.

A man answered after a few short rings.

“Hello… is this, um, Snurfer?” I said, not sure why I expected anything else.

It was indeed. Mike Jenkins, current co-owner of Snurfer, began excitedly guiding me to where and how I can get my hands on a board, and which one was best for me.

Mike walked me through the last few years of Snurfer and how he and his brother got involved.

The ownership over the Snurfer had changed hands over the years from one company to the next, but in 2021, the two Jenkins brothers came into the picture, taking over the business from a colleague who couldn’t keep up with the new demand.

The Jenkins brothers took the operation to Salt Lake City, where they are from, but it wasn’t quite right. As they continued learning the history of the Snurfer, it naturally brought them to Michigan. Mike said, “We felt a call.” It’s now based in Spring Lake.

Mike had never stepped foot in Michigan before. “We’ve been everywhere with the Snurfer, Salt Lake, Vermont, but here it just feels right. The people, the spirit; it’s alive here,” Mike said.

Mike told me they are preparing to grow their operation and are in the middle of restructuring to handle the increased demand in production. “We’ve been staying quiet, but we have some big things coming.”

They’ve been moving slowly and learning as much as they can so they do right by Poppen and his Snurfer.

It’ll be just in time. Mike reminded me, “This year is the Snurfer’s 60th anniversary.”

We can’t wait to celebrate.

Devinn Dakohta is a contributing writer for Michigan Enjoyer. Follow her on Instagram @Devinn.Dakohta and X @DevinnDakohta.