Detroit — The city is overwhelmed by crime—the violent crime rate is nearly five times higher than the national average—and many citizens enthusiastically support any measure to improve public safety. When homicides and carjacking are commonplace, concern over privacy rights are abstract.

Many claim we must choose either safety or privacy rights, but it’s time to reconsider crude deterrence, the unsophisticated and effective third way. We should look at Rudy Giuliani’s policies in New York City.

Detroit presents an interesting case study. Biometric analysis, and specifically facial-recognition software, has been used here with mixed results.

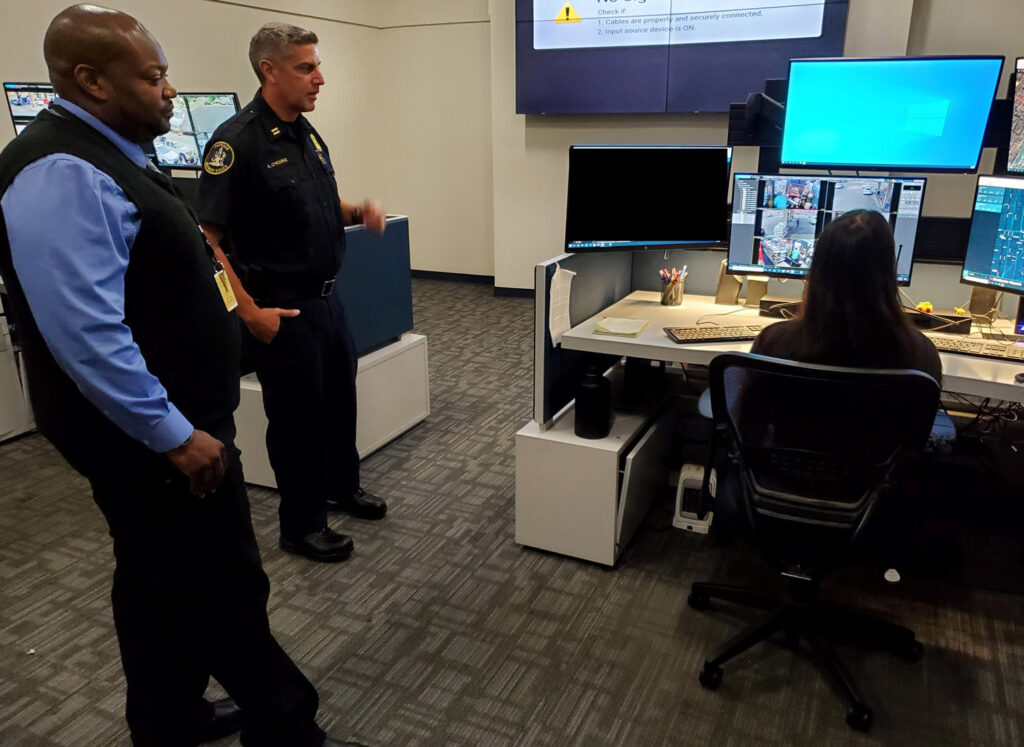

One such security initiative was Project Green Light, which launched in 2016. It first started at 24-hour gas stations, transmitting a live video feed to Detroit’s Police Department’s Real-Time Crime Center, where operators could monitor people on premise, analyze behavior, and respond to crime in real time. After a year of operation, residents of high-crime Regent Park neighborhood were marching on their local gas station, pressuring the owner to join the initiative, despite the expensive cost associated with installation, which ranges between $4,000 and $6,000. They even entered the business with the application to get the paperwork filled out on the spot. Project Green Light now has over 1,000 partners, spanning liquor stores, fast food chains, and places of worship.

But, in the same year, the Detroit Police Department acquired controversial facial-recognition software from a company called DataWorks Plus, which can compare images from photo banks full of mugshots and driver licenses, as well as footage from private cameras and social media, to identify suspects.

I called DataWorks Plus and asked for a media representative. They first clumsily provided me with the general email to Green Light Project (no more helpful), telling me that they were “more or less the same.” When I asked the operator if I could quote him, he recanted the statement, “well no, actually, we’re completely separate entities.” He then told me there was no one at DataWorks I could speak with, and that they don’t have anyone who takes questions. Interesting.

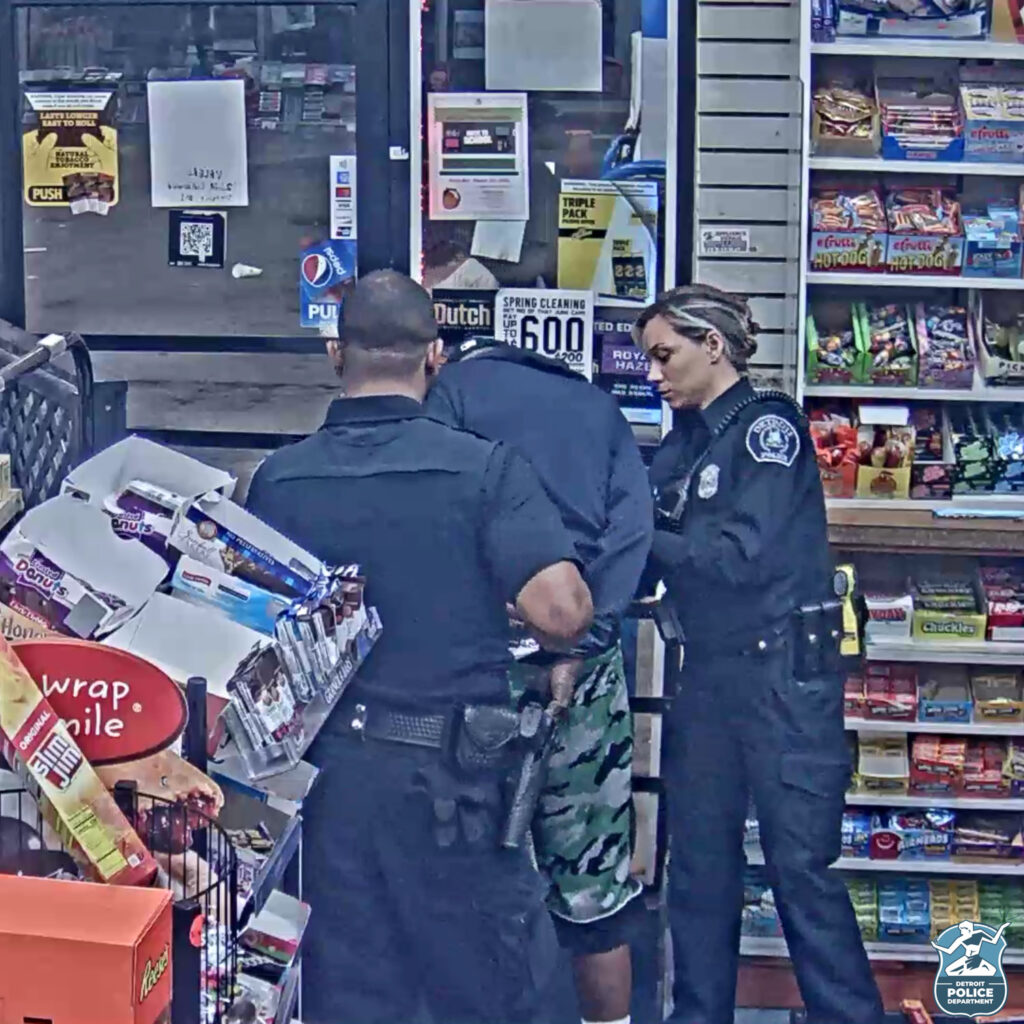

They are doubtlessly afraid of probing and scrutiny. This last summer, the City of Detroit paid $300,000 in a settlement to a man wrongfully arrested for shoplifting. He claimed that the police used racially biased technology, specifically facial recognition software, that is worse at identifying black faces than those of other races. Since then, the cops have put some guardrails in place. Now a photo match must be corroborated with independent evidence. The ACLU is calling updated Detroit policy the American standard.

Businesses seem very happy with Project Green Light overall, according to liquor store owners I spoke with. The cops recommended I visit Riverside Liquor on Jefferson and ANA on Gratiot, which are allegedly liquor stores with the most criminal activity. So I did. But the owners were baffled by the suggestion made by the police. The liquor store proprietors told me that they see very little criminal activity. Furthermore, they say that since the camera installations, they have seen virtually no theft, which was their biggest issue. Project Green Light has not been associated with any reductions in violent crime, though the owners are of course protected by bulletproof glass. There’s also a chance they wanted to downplay crime to avoid a bad reputation.

I then visited Diane’s Liquor Store at Joy Road and Schaefer Highway. People were drinking in the parking lot and inside their cars. On my way out, everyone was driving away frantically. The police were making an arrest in the parking lot, having likely identified the license plates from camera footage. The men were arrested before they could even enter the business. This is the advantage of surveillance.

Project Green Light, like DataWorks, was impenetrable. I tried making a media request and was relayed from one person to the next. When I was finally given time for an interview, I was confirmed a time for the next day. But then, no one called. I tried again and got another time: 10 months away. Unbelievable, and likely a mistake, but part of a general trend of incompetence. I complained and was given another time another week away. One rescheduling after another, ad infinitum. How many police station workers are siphons for money that could be used more productively elsewhere?

Detroiters prefer intrusive surveillance to the default of carjackings, robberies, and violence. Marginal improvements—even through controversial measures that violate privacy, executed by companies shrouded in secrecy and overseen incompetent city management—are still improvements.

But there is another way. An alternative that respects privacy, one that’s proven effective without the need for surveillance.

I call it the Giuliani model. In the 1990s, NYC’s huge problem with crime fell dramatically. Violent crime dropped by 56%, and property crime declined by 65%. The cause? Aggressively prosecuting lower-level crime. This is called the ”broken windows” approach.

The Giuliani model requires moving resources away from administrators, out from behind phones and computers, to officers enforcing crimes on the streets. It is that easy. New York’s crime problem was thought to be an impossible situation, but the city government reversed the trend through simple policies: arresting for misdemeanors, eradicating graffiti, cracking down on fare evasion on the subway, and implementing stop-question-and-frisk programs.

Detroit could use the same playbook. Sometimes the solution to crime isn’t sophisticated technology, it’s just having balls to use deterrence.

Mitch Miller is an adventure writer and conflict journalist. He’s more than happy to join in on any extreme activity, and can be reached at mitchenjoyer@gmail.com. Follow him on X at @funtimemitch.