Grindstone City — I was already in the area when I turned toward the lake. It was the middle of winter, when Michigan is reduced to only what it needs.

Everything felt exposed—bare trees, flat fields—long stretches without interruption. The farther east I drove, the more it felt like the road itself was being pulled toward Lake Huron.

Grindstone City didn’t announce itself. There was no clear moment of arrival. The pavement narrowed, the trees thinned, and the lake appeared—gray, restless, and visibly frigid. Even from inside the car, it was obvious this shoreline had never been gentle.

I didn’t park for long. I didn’t go inside anywhere. I just drove through.

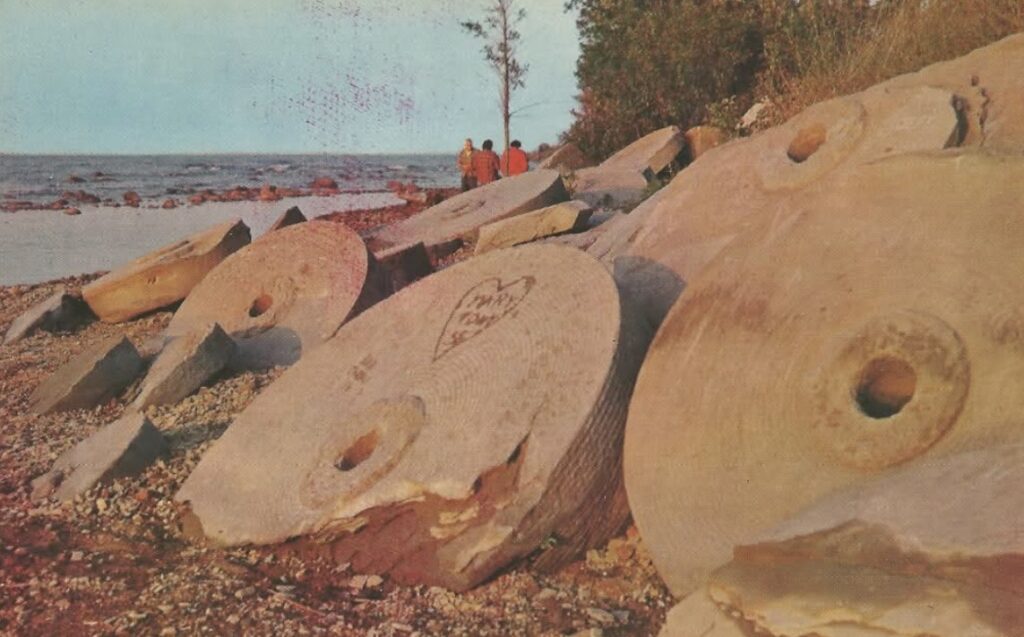

The grindstone marker was the first thing that made the place make sense. Large and heavy, dusted with snow, it felt less like decoration than evidence. Grindstone City wasn’t built for scenery or retreat. It existed because this stretch of shoreline held something rare: a dense, durable sandstone perfectly suited for grindstones—the massive wheels once used to sharpen nearly every tool that mattered.

The story goes back to the 1830s, when a Great Lakes ship captain named Aaron G. Peer took shelter here during a storm. While waiting out the weather, he noticed the stone along the shore and realized its value. What began as a chance observation turned into an industry. By the mid-1800s, Peer had purchased hundreds of acres and begun quarrying the stone in earnest, laying the foundation for what would become Grindstone City.

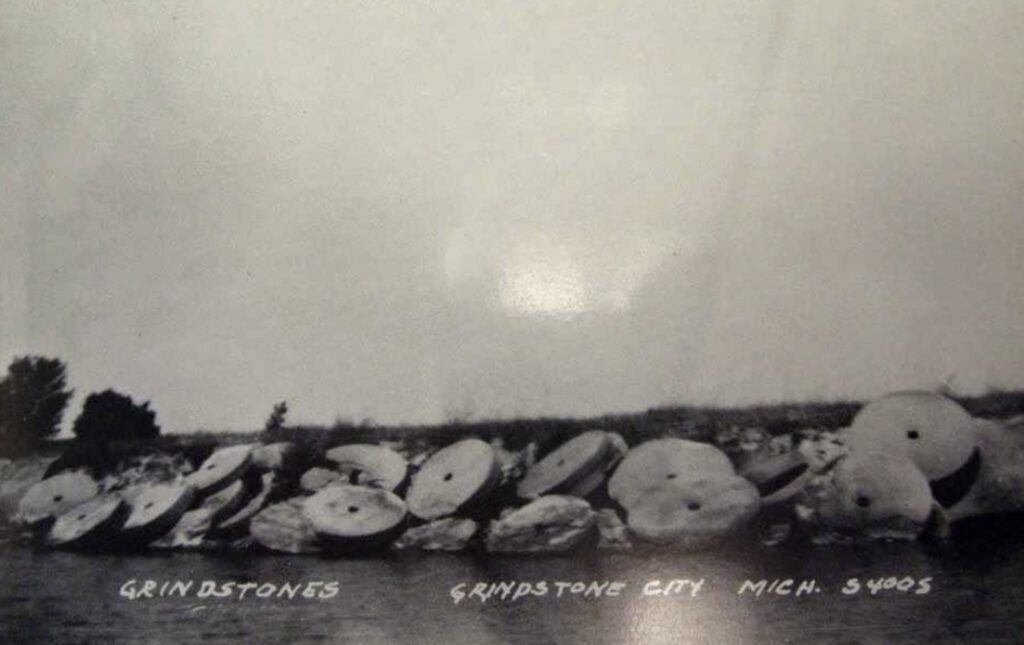

Before electricity and power tools, grindstones were essential. Axes dulled. Scythes lost their edge. Chisels wore down. Without sharpening, work simply stopped. Along this shoreline, workers cut massive stone wheels directly from the earth, shaped them by hand, and hauled them down toward the lake. From here, they were loaded onto ships and sent across the Great Lakes to farms, mills, and factories hundreds of miles away.

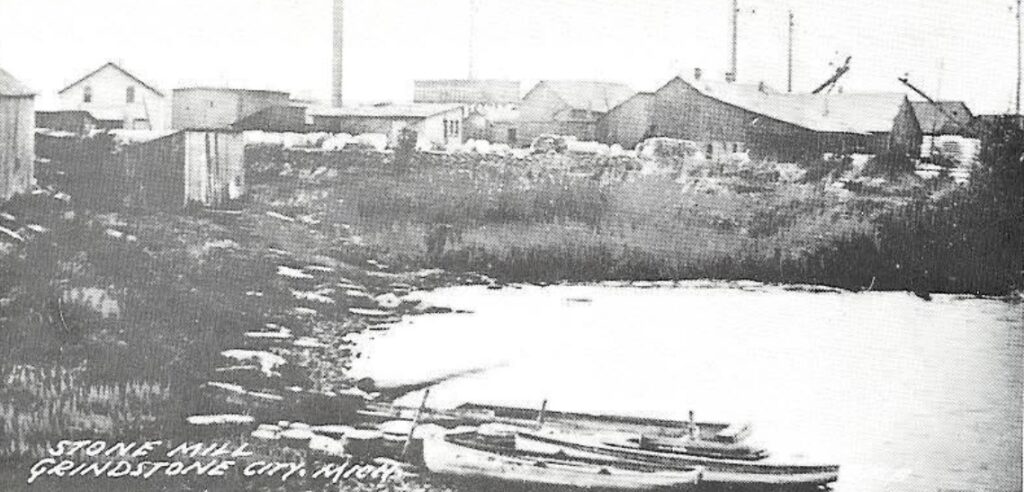

By the late 19th century, Grindstone City was entirely built around stone production. Two major operations—the Lake Huron Stone Company and the Cleveland Stone Company—employed hundreds of workers. The town supported docks, company offices, housing, and a growing population that peaked at around 1,500 people. A railroad even reached the town, built so shipments wouldn’t have to rely entirely on lake conditions.

Winter didn’t stop the work so much as it hardened it.

You can picture a quarryman near the shoreline, breath turning white as soon as it leaves his mouth, boots stiff with cold by mid-morning. Stone dust settles into the cuffs of his coat and never fully leaves. Out on the lake, a ship waits behind a skin of forming ice, its departure dictated by wind and temperature instead of schedule. The grindstones are already cut—perfect circles resting near the dock—waiting for the lake to decide when it will let them go.

That sense of permanence is still visible if you slow down enough to notice it.

The general store came next. It’s closed now, dark against the winter sky, holding its ground against the wind. In a working town like this, a store wasn’t a novelty or a stop for visitors. It was infrastructure. A place for food, tools, mail, and news—especially in winter, when ice could delay shipments and the road out became harder to trust.

Farther along stood the school. Solid. Overbuilt. Schools are quiet expressions of confidence. You don’t build one unless you expect people to stay—unless you believe children will grow up, graduate, and be replaced by younger ones. At one point, that belief made sense here.

Eventually, the reason for the town began to disappear.

The decline wasn’t sudden or dramatic. In 1893, the invention of carborundum, a synthetic abrasive, changed everything. It was cheaper, more consistent, and easier to produce than natural stone. Factory sharpening followed. Disposable blades came later. Demand for traditional grindstones collapsed.

By around 1930, the quarries along Lake Huron shut down for good.

Grindstone City didn’t vanish. It didn’t burn or empty overnight. It simply contracted. What remains today is part of the Grindstone City Historic District, roughly 250 acres recognized on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971. Much of the quarry land has been reclaimed by trees and shoreline, the work softened by time, snow, and wind.

In winter, that history feels easier to read.

Driving through, the town felt finished rather than forgotten. Wind moved freely through spaces where industry once stood. Snow softened the edges of buildings that had been built for labor, not comfort. There were no signs asking me to stop, no open doors promising warmth, no attempts to turn history into an experience.

I kept moving, hands steady on the wheel, the lake slipping back behind the trees as the road widened again. Grindstone City receded quietly, unchanged by my passing.

Michigan is full of places like this, towns built for a single, practical purpose, now resting beneath snow and memory. You don’t stop for them anymore, but the work they were built for is still obvious.

Landen Taylor is a musician and explorer living in Bay City. Follow him on Instagram @landoisliving.