Lansing — At the Michigan State Capitol, the memorials are all about the Civil War. Battle flags from Michigan regiments line the inside of the rotunda. Civil War cannons and statues dot the lawn. Coated in glory, they lay claim to Michigan’s emergence as a state.

Modern Michigan wasn’t forged in the Civil War, however, but in Vietnam. A lone memorial, far off to the west of Lansing’s sprawling Capitol complex, is dedicated to Michigan’s Vietnam veterans and shows how that war remains central to the mythos of our state.

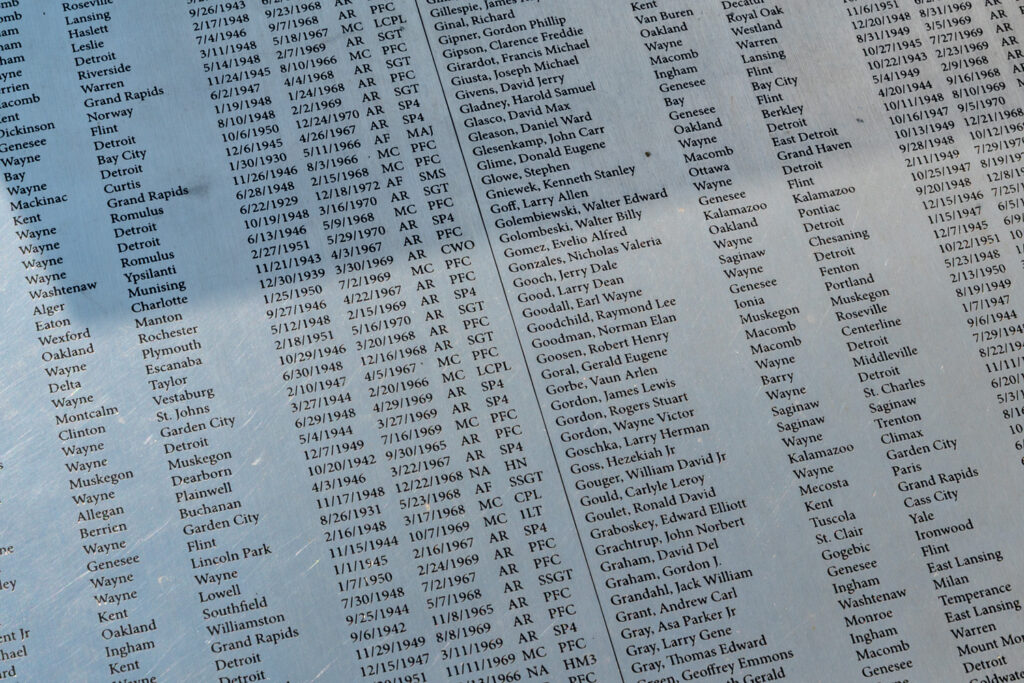

Nearly 400,000 Michiganders served in the Vietnam War; 2,651 of them were killed or missing in action. The Michigan Vietnam Veteran’s Monument is dedicated to them.

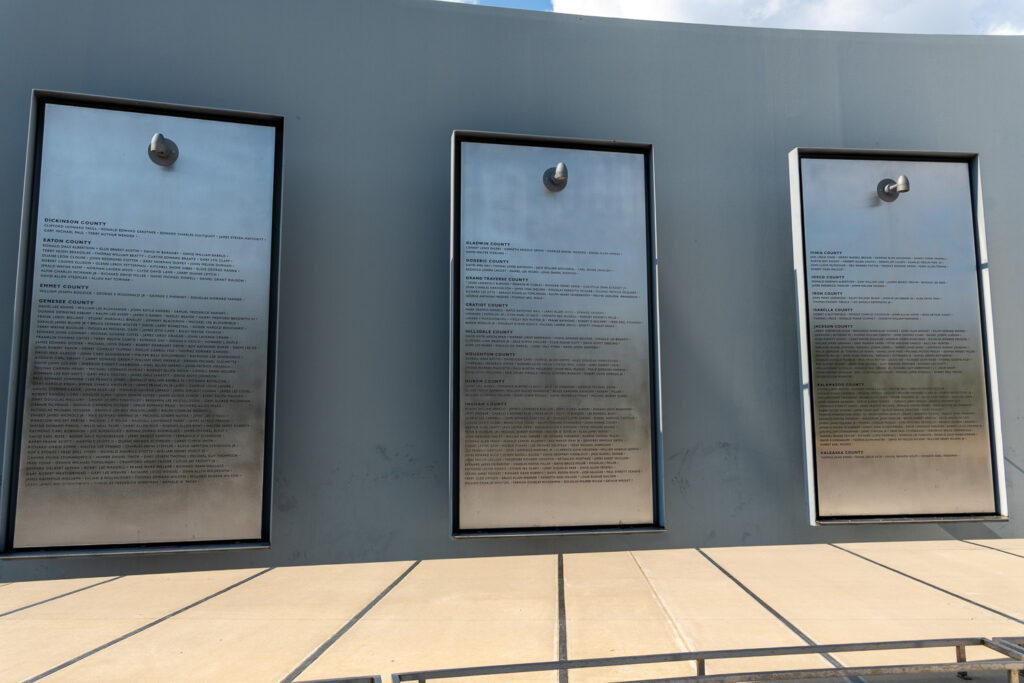

A sweeping plaza of dark, square stones surrounds the monument. The monument itself is a heavy, steel wall spanning 120 feet, held 3 feet off the ground by steel suspension cables. It curves inward, inviting the viewer in closer to walk alongside it.

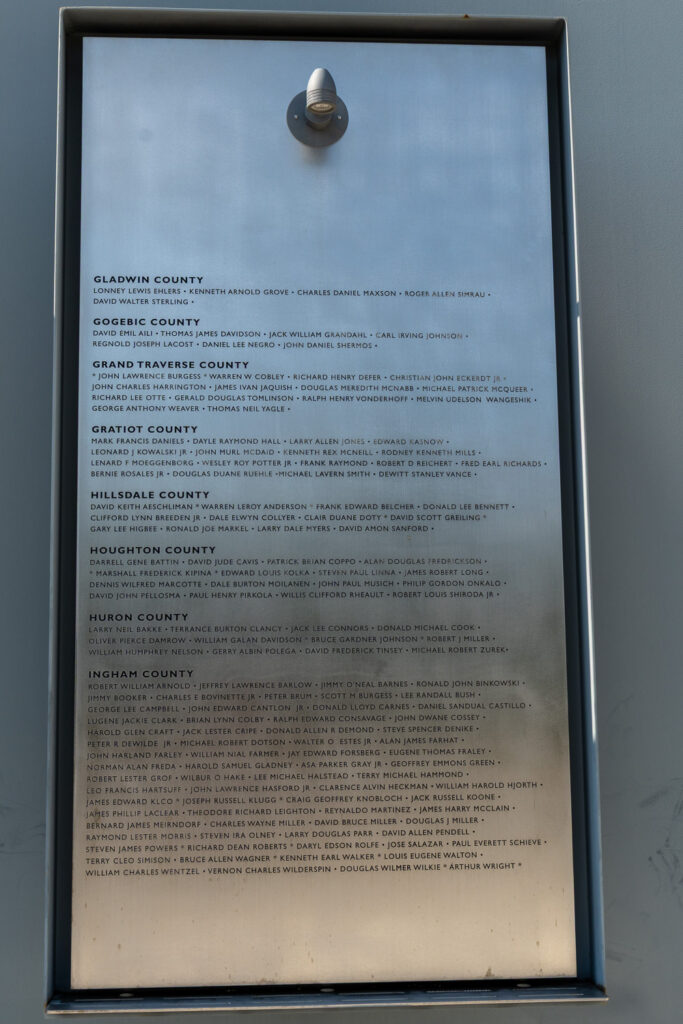

Fifteen large steel plates hang to create the interior surface. They’re inscribed with the names of Michigan’s fallen, each listed by their county of origin. Every county in Michigan is represented, from Wayne County to the furthest reaches of the Keweenaw.

A timeline of the war stretches across the exterior surface of the steel wall, with key events of the war listed by date and helicopter murals overhead. Walking along it, you feel the length of history, as the war played lasted nearly a decade.

The monument took nearly 13 years of planning, fundraising, and advocacy by Vietnam veterans. The state passed an act in 1988 authorizing a planning commission, and another one in 1992 setting aside the land.

After raising $3.2 million in a mix of public and private funds, the site was dedicated in 2001, with former President Gerald R. Ford in attendance. Designed by architect Alan Gordon, the final design was chosen after a national competition with more than 200 entries.

Clearly, the design is derivative in some way from “The Wall,” the larger Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. inscribed with the names of the entire country’s casualties. Finished in 1982, it has since encapsulated the public consciousness regarding the war.

It was controversial at first. Ross Perot, the later presidential candidate, withdrew his support entirely after seeing the design. James Webb, the later secretary of the Navy under Ronald Reagan and senator for Virginia, called it a “nihilistic slab of stone.”

Since then, the controversy vanished, and the memorial has been embraced as something of a shrine. It leaves a deep impression on visitors, the weight of the stone, the near incomprehensible number of names: Each one of them a person, a young man killed in a war fought far away from home.

Michigan’s memorial has the same effect. Wandering through these empty governmental plazas, it stopped me in my tracks. So many names, thousands of them, each with a story, each killed in service to the nation.

Each one had a home here in Michigan. Listing them by county, a small detail, makes the monument all the more poignant. These were Michiganders, from our towns and cities, with boyhoods spent in our own backyards.

Yet when the war was over, no one wanted to remember it. There were no victory parades, no celebrations, no statues to victory.

Even worse, the soldiers were spat upon, as far-left groups like the Weather Underground, founded in Ann Arbor, rioted and carried out political violence across the country. Michigan was central to the national political debate then, as it is now.

These were hard years for Michigan. Factories and jobs shipped overseas, cities fell into stagnation and declined. We all know the story of those years, of what befell the Vietnam generation. The war was hard, and so was their homecoming.

Michigan endured, and the veterans remembered their service. They still do, they’re still around, the war remains in living memory. The effects, too, are still ongoing—even recent protests in Lansing centered around ethnic groups like the Hmong, who fled to Michigan as refugees after the war.

As such, the monument is all the more poignant. You can read the names on the monument and imagine yourself, your brother, your father or grandpa. You can picture these men, fighting for America in a faraway land, and feel the sacrifice they made.

You can feel the weight of generations of Michiganders, striving to make our state great, despite the hardships and antagonism they’ve endured.

There are no monuments to their victory—only to their sacrifice, to the lives lost, the effort made.

They fought bravely and honorably and deserve to be remembered. The monument in Lansing is a fitting testament to them, and to their central role in Michigan’s history. The Capitol building may claim the Civil War, but modern Michigan finds its legacy in Vietnam and this lone plaza dedicated to its veterans.

Bobby Mars is art director of Michigan Enjoyer. Follow him on X @bobby_on_mars.