Bath — Andrew Kehoe, the school board treasurer for the Bath school district, wrote a letter dated May 14, 1927, to insurance agent Clyde Smith.

Kehoe wrote that, due to an uncashed check, the school band had 22 cents more in its account than his books showed. Kehoe noted the local bank also gained one more cent from the district than his records showed.

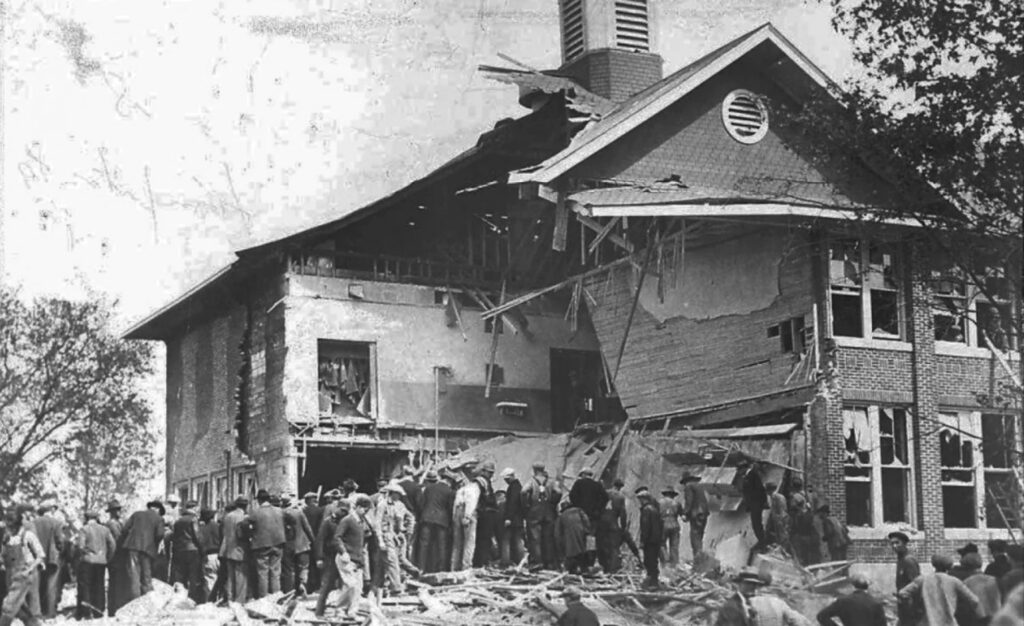

The letter was sent in an empty dynamite box. It was empty, because four days later, Kehoe would use the explosives to blow up the Bath school building and kill 38 school children and six adults in what is considered one of the most heinous acts of terrorism in this country’s history.

The 55-year-old farmer wanted to blow up all 260 school children in attendance that day. Despite his impeccable planning, one of his charges miraculously didn’t go off, and investigators on the scene after the bombing found more than 500 pounds of dynamite still intact, enough to blow up the entire village that was just a mile away.

As Michigan residents grapple with the more recent assassination of Charlie Kirk, a Christian father of two young children, and a shooting rampage at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Grand Blanc that killed five, including a six-year-old, Andrew Kehoe’s story is a stark reminder that evil has lurked among us in Michigan for nearly 100 years.

Sometimes, like with Kehoe, it is cloaked in the veil of normality.

The day before the bombing of the two-story school building that would leave debris of wood, plaster, and brick 10 feet high, first-grade teacher Bernice Sterling called Kehoe at his home a half mile away to ask if they could use his farm for the annual school picnic.

“When are you going to have the picnic?” Kehoe asked the teacher.

She told him it would be Thursday, the day after Kehoe had planned to bomb the school.

“Well, if you’re going to have a picnic, you’d better have it right away,” Kehoe told her.

Kehoe had purchased the farm in Bath in 1918 after arriving from Tecumseh. He was an educated man, graduating from Michigan State College. Kehoe had a great knowledge of electricity and a reputation of being able to could fix anything.

While he and his wife were childless, Kehoe had grown to despise the school district. His mortgage was foreclosed months before the bombing, something he blamed on the creation of the consolidated school system which drew students from the farms in the region and raised taxes.

Neighbors and acquaintances said Kehoe had become obsessed with the school and the taxes. He feuded with Bath Superintendent Emory Huyck over the school.

In his final year, neighbors said Kehoe didn’t harvest the corn on his 80-acre farm, and his previous year’s bean crop had rotted.

His wife, Nellie, had become ill and had spent time in hospitals in Lansing, Detroit and Ann Arbor during that time, too. Kehoe’s family members believed the cost of her illness may have been what triggered him.

In the spring, Kehoe didn’t make any attempt to farm his land, despite having all the tools, including a tractor.

Investigators believe the plot to blow up the school took months of planning. As treasurer, he had a key to the school building. The school janitor said Kehoe had been working in the basement of the school building for several weeks.

After the blast, investigators found unexploded sticks of dynamite in ventilator openings, baseboards, in the walls, behind pipes “and tucked away in every conceivable spot throughout the lower portion of the building,” according to newspaper accounts.

The bomber had made openings in the walls to fill with dynamite, and long pieces of gutter pipe were also filled with the sticks of explosives.

Police found fishing poles that the bomber used to put the dynamite in the walls and gutter pipes. Each joint in the electrical system linking the dynamite had been soldered and taped.

“Kehoe was taking no chances on a slip,” the Grand Rapids Press reported in the days after the bombing.

He also had planted several sticks of dynamite behind the office of his nemesis, Superintendent Huyck.

Kehoe started his last day by crushing his wife’s skull with a hammer and leaving her in a cart. He put her body in a building he was going to burn down.

He set off dynamite in his home by connecting the wires to the battery of his truck, the same way he would detonate the dynamite he buried within the school.

With his home in flames, Kehoe took off for the school.

Kehoe’s neighbor, George Hall, saw Kehoe’s farm go up in flames after the explosion, and other nearby farmers rushed to help his neighbor. One of the neighbors went into Kehoe’s house and then ran out, warning the other farmers that “there is enough dynamite in there to blow up the county!”

Hall, who had heard Kehoe’s rants about the burden the school was creating with higher taxes, was worried Kehoe may try to damage the school building and drove to the school where he had two children in attendance.

When Kehoe got to the school, it is believed he detonated the bomb and then drove off.

School had been in session for about an hour.

Pauline Mol, 12, was listening to her teacher tell a story and then heard a big bang, and the school ceiling collapsed on her. The plaster and smoke was so thick that a principal said he couldn’t see his hand in front of his face. Soon, men arrived to dig Pauline out of the rubble.

Student Billy McCoy was taken to the hospital in Lansing, covered in lacerations and with a broken leg.

“This building won’t blow up, too, will it?” Billy asked his doctor.

The explosion was so devastating, homes half a block away had their windows shattered and plaster torn from the walls.

But while driving away, Kehoe must have sensed something had gone wrong. The explosion wasn’t nearly as big for the amount of explosives he had planted. What he didn’t know was there was a broken circuit in one of his connections. Why the terrific explosion didn’t set off the rest of the dynamite was a mystery to investigators.

Realizing his plot to blow up the entire school had failed, Kehoe turned his truck back to the school district for his final act of depravity. Superintendent Huyck had rushed outside of the school after the explosion. Kehoe saw Huyck had survived and called for the 33-year-old superintendent to come over to his car.

When Huyck arrived, Kehoe took out a pistol and shot into a load of dynamite in his car, creating another huge explosion and instantly killing himself, Huyck, and two other men that were standing next to his truck.

Kehoe’s neighbor George Hall had arrived just in time to witness Kehoe calling over the superintendent to his car. Hall was then blinded by the explosion. Investigators would only find Kehoe’s driver’s license in a tattered piece of clothing.

Hall would soon find out his daughter, Willa, and his son, George, Jr., both perished in the school explosion.

No one in the community was spared. Everyone had a daughter, son, or close relative who was killed in the blast.

One out of every four children in the village of 300 were killed that day. There were 38 children killed. The youngest to die was six-year-old Marjorie Fritz. The oldest were 14-year-olds Henry Bergan and Loren Hunter.

Teacher Hazel Weatherby’s body was discovered in the rubble. Underneath each of her arms were the bodies of two young children she had unsuccessfully tried to save. The children’s small hands were still gripping their teacher’s garments.

The bodies of the young children were laid out on the school grounds in a make-shift morgue and covered with blankets.

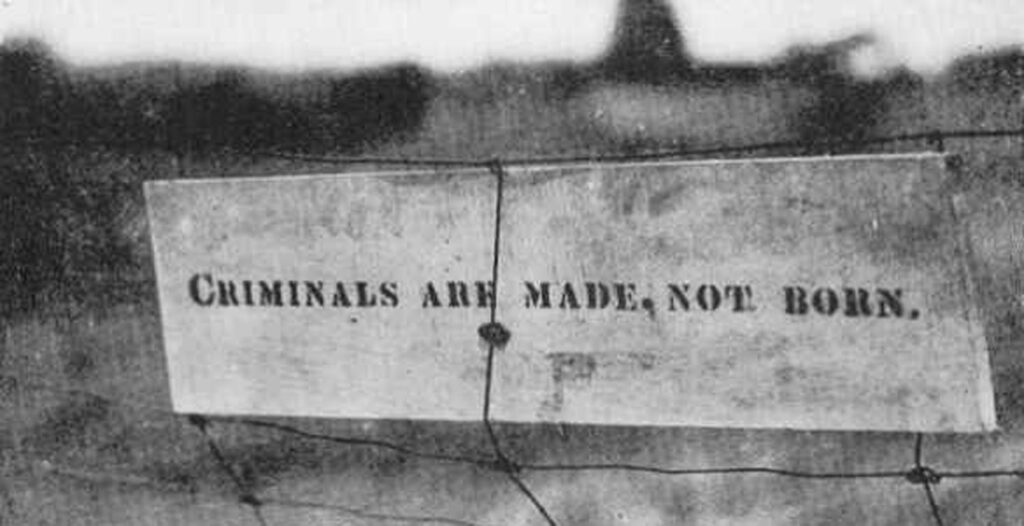

When investigators later combed through the remains of Kehoe’s farm, they noticed a sign on the fence in the rear of his farm.

The sign read: “Criminals are made, not born.”

Tom Gantert is a contributing writer for Michigan Enjoyer.