Jocelyn Benson’s election nonprofit never raked in much money.

Then, in 2020, came the Zuckerbucks, and a new mission: Fortify the election. Count every vote. Before 2020 and since, the nonprofit failed to hit the $50,000 donation threshold required to file a full report to the IRS. It had only to file a postcard.

But in 2020, the nonprofit received a $12 million grant on the eve of the presidential election.

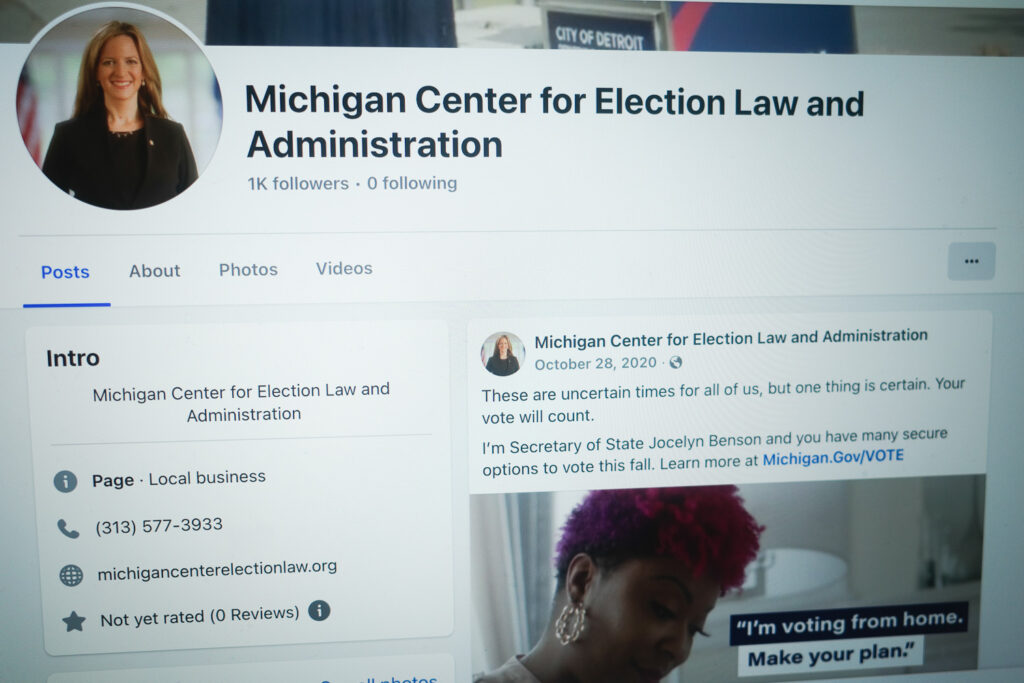

The Michigan Center for Election Law and Administration was granted 501(c)(3) nonprofit status in May 2010, when Benson was running for Michigan Secretary of State for the first time.

Benson lost that November to Ruth Johnson. And in the years that followed, the center seemed to exist mostly to bolster Benson’s reputation as an “election expert.” In 2012, when the city of Detroit drew a new map for city council districts, Stephen Henderson, then-editorial page editor of Detroit Free Press, sniffled that Benson “was not used as a resource.” Why would she be? Because in 2011, her nonprofit held a citizen competition to draw Michigan’s new legislative maps.

It worked. In 2018, Benson was elected to the first of two terms as secretary of state, and left the nonprofit. Benson would go on to administer the 2020 and 2024 presidential elections—a high visibility role in a swing state.

The nonprofit continued to languish—until the 2020 presidential election, when so-called voter outreach efforts, in a year of mail-in voting, attracted big money.

Then Benson and her old nonprofit teamed up once again, this time with Benson outside the nonprofit and inside the government. This drew little scrutiny at the time.

Here’s how Michigan Public Radio reported on the $12 million grant:

“A voting education group has launched a new initiative in collaboration with with Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson. The statewide non-partisan initiative will be run by the Michigan Center for Election Law and Administration (MCELA) and explain to people the options for how to vote safely and securely during the pandemic.”

“Your vote will count whether you’re at the polls on election day,” Benson successor Jen McKernan, president of the nonprofit, told the radio network. “Your vote will count whether you mail in your ballot or drop off your ballot at your city clerk’s office.”

Benson’s founding role in the nonprofit is never mentioned, and the conflict-of-interest is never explored.

Both the Zuckerbucks and the state-nonprofit collaboration were treated as good news, not as troublesome.

MCELA got its $12 million from a non-profit called the Center for Election Innovation and Research.

The D.C.-based center was boosted by a $50 million donation from Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. Ultimately that number would reach about $70 million. The donations came from the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, which spent $400 million on the 2020 election.

But Zuckerbucks touched election officials directly, too.

Through another nonprofit, the Center for Tech and Civic Life, $16 million was routed to 465 Michigan communities “to buy supplies” for the 2020 election.

Here’s how Time Magazine described the supplies election officials bought, in its infamous story on how 2020 was fortified:

“The first task was overhauling America’s balky election infrastructure–in the middle of a pandemic. For the thousands of local, mostly nonpartisan officials who administer elections, the most urgent need was money. They needed protective equipment like masks, gloves and hand sanitizer. They needed to pay for postcards letting people know they could vote absentee–or, in some states, to mail ballots to every voter. They needed additional staff and scanners to process ballots.”

One month after election day, National Public Radio insisted that Zuckerbucks had “saved” the 2020 election.

Litigation to stop Michigan election officials from accepting such private donations went nowhere.

A 2022 effort to ban Zuckerbucks, led by former Benson adversary Ruth Johnson, went nowhere.

With Democrats controlling Lansing the next two years and lawmakers unable to even pass a budget in 2025, outside funding for elections is rarely discussed.

As Benson runs for governor in 2026—an election she will administer as Secretary of State—Michigan is as open to outsider meddling as it was in September 2020.

And the Michigan Center for Election Law and Administration sits dormant, one grant away from springing again into action.

James David Dickson is an enjoyer of Michigan. Join him in conversation on X @downi75.