A small liberal-arts school in Michigan educated one of the most successful codebreakers in American history.

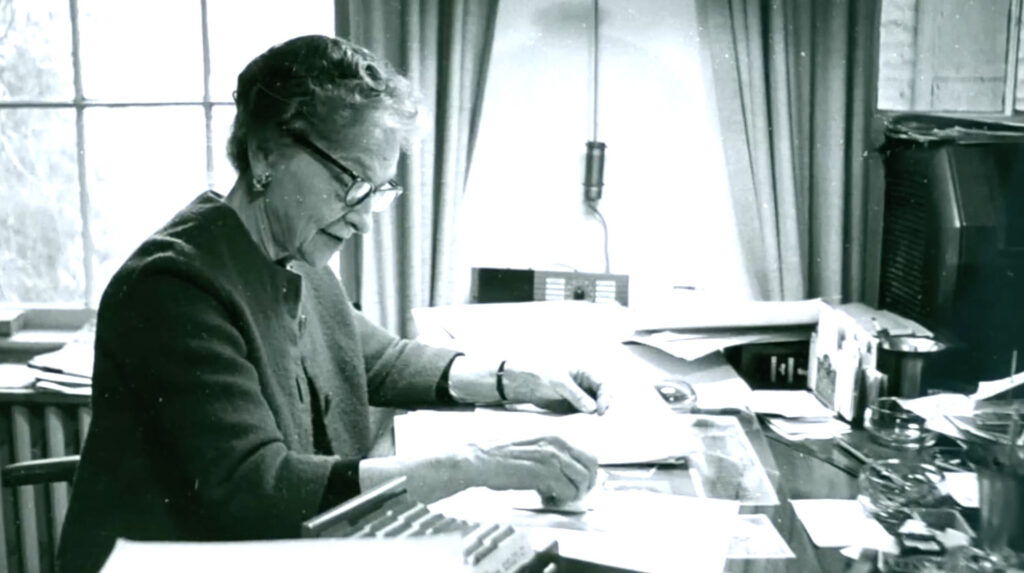

Elizebeth Smith Friedman studied Greek and English literature at Hillsdale College, graduating in 1915. She was involved in a sorority, edited the school’s newspaper, and performed some Shakespeare.

Her introduction to codebreaking came about because she was reading William Shakespeare at a Chicago library in 1916. The librarian noticed her and called George Fabyan, a wealthy, eccentric businessman who had established Riverbank Laboratories as a private research center.

When Fabyan and Elizebeth met, he convinced her to work for him at Riverbank. He had a theory that Shakespeare was not the true author of his plays, but rather a man named Sir Francis Bacon. He believed there were hidden codes and ciphers contained in his writing that would prove this theory.

Elizebeth had no experience in codebreaking but she was eager for an adventure, after finding her first job out of college, teaching, less than exciting.

During this time, she had to master a method of encoding messages. The work was tedious, but she loved the challenge. She also met her husband, William Friedman, while working at Riverbank.

Although the Friedmans enjoyed the tedious work, they came to the conclusion there was no evidence of Bacon writing Shakespeare’s play. After this realization, Elizebeth saw no future in codebreaking.

But then, the U.S. entered World War I.

With the invention of radio, the air was full of messages relaying important messages that could be intercepted. Codebreaking became more important than ever, but the U.S. was extremely unprepared, without a codebreaking agency.

This gave Fabyan the opportunity to establish the first dedicated codebreaking unit in America at Riverbank, and he placed Elizebeth and William in charge. The Friedmans began breaking codes for the U.S. military in a world war. Their success or failure would determine the fate of the nation.

They began decrypting messages using frequency analysis. Elizebeth was very good at spotting patterns. Eventually they reached the limits of what was known about coding, so they invented their own methods.

In the first eight months of the war, Elizebeth, William, and their colleagues broke all messages for every part of the U.S. military and Justice Department. But not only that—Elizebeth was training the first generation of codebreakers for the U.S. military.

As the workload at Riverbank dwindled, William signed up for military duty as a field codebreaker in Europe. Elizebeth wanted to join, but couldn’t since she was a woman.

In 1921, William went to work for the Army Signal Corps to develop new cipher machines. Elizebeth was offered a job, but at half of William’s salary. She left after a year, believing her codebreaking days were over.

But in 1926, a Coast Guard officer arrived at Elizebeth’s home with an urgent plea for help.

Their radio towers had intercepted hundreds of encrypted messages, but no one could decipher them. Prohibition was in full swing, and the Coast Guard was struggling to stop liquor smuggling. Hoping to disrupt organized crime, she agreed to help.

In just three months, she single-handedly decoded two years’ worth of backlogged messages. But she didn’t stop at breaking codes—she transformed raw intelligence into actionable strategy. She could identify who owned the smuggling vessels and predict their movements, allowing the Coast Guard to intercept shipments and prosecute offenders.

Her success led the Coast Guard to approve her proposal to create an official codebreaking unit, the first ever led by a woman. She later served as the star witness in trials that brought down major criminal figures, including Al Capone.

In 1941, Elizebeth’s team shifted its focus from supporting the Coast Guard to working directly with the Navy. Her most significant achievement during World War II was dismantling the spy network of Johannes Siegfried Becker, known by the codename “Sargo,” a top SS agent and one of Hitler’s key operatives in South America.

She also decoded critical messages revealing the positions of German U-boats in the Atlantic, helping to safeguard vital Allied supply routes. This was vital to America’s success in the war.

Despite her extraordinary success, her work remained hidden. Bound by a lifetime oath of secrecy, she could only describe her role to friends as a “routine Navy job,” never revealing the true extent of her contributions.

American FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover took the 4,000 decrypts Elizebeth had sent and had them stamped with FBI identification numbers. Elizebeth and her team were erased from the official records.

Despite creating a new science of codebreaking, she died poor in a nursing home in 1980.

The government kept her files secret for 62 years. In 2008, they were finally declassified.

Had Elizebeth not attended that tiny Michigan college and found her love of Shakespeare there, she probably would have never met Fabyan, who introduced her to codebreaking.

What began with Shakespeare’s verses in a library became the foundation for dismantling spy rings and saving lives across oceans.

Lauren Washburn formerly served as a research analyst for Dr. Phil Primetime and currently works as Christopher Rufo’s executive assistant.