What’s smaller than a sesame seed, tougher than a Michigan winter, and just showed up uninvited to our Michigan woods?

Meet the Asian longhorned tick, discovered last week by Calvin University students (go Knights) at Grand Mere State Park in Berrien County. This invasive species, confirmed by USDA labs, has now arrived in Michigan, along with 21 other states. If you like to hike or have any animals outside, you need to be paying attention.

Michigan’s wild places have always tested us. Our ancestors endured blizzards to trap beaver, and voyageurs paddled through clouds of mosquitoes to map these lakes. But now a brand new challenge has arrived, one that doesn’t howl or leave tracks but can bring a fully grown cow to its knees.

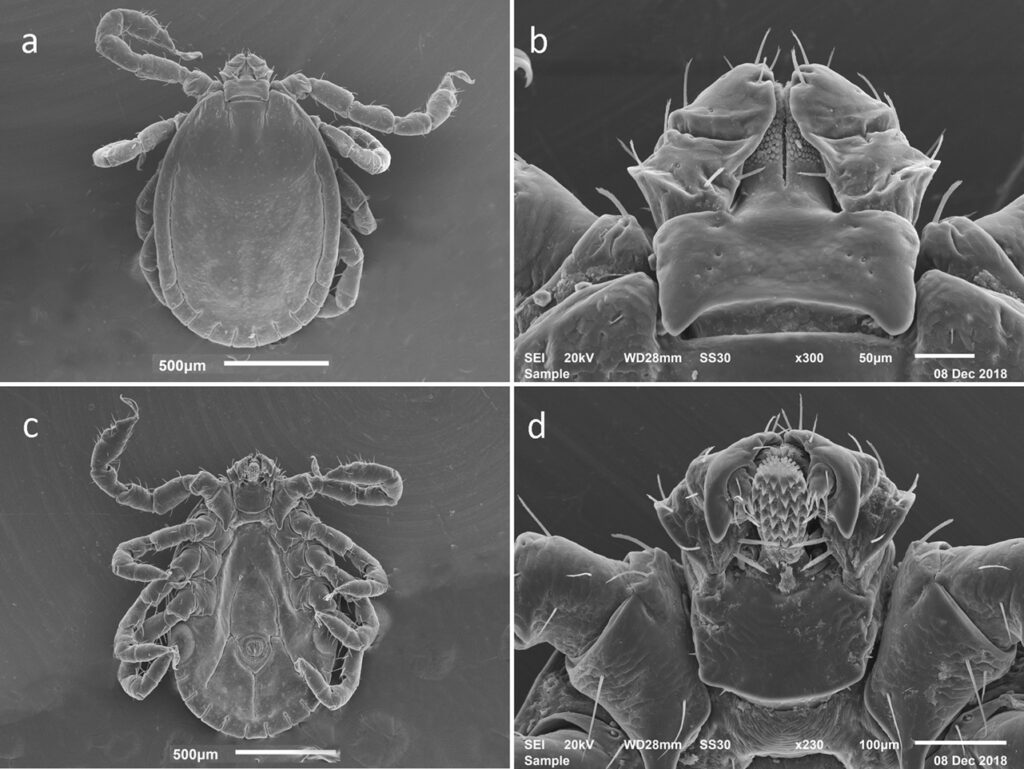

Since 2017, Asian longhorned ticks have been spreading from New Jersey, creeping through Ohio and Indiana, and last week they officially hit Michigan. These aren’t like the deer ticks we’ve grown accustomed to the last few years. They’re a different beast, tiny, relentless, and quick to reproduce.

A single female can spawn 2,000 eggs without even having a sexual partner. Each egg hatches into a clone, ready to drain blood from anything warm: deer, dogs, cattle, chickens, you. It sounds like something out of an Alien movie… well, it’s not far off.

They also carry a big range of diseases, like Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Powassan virus, Heartland virus, and a parasite that causes bovine theileriosis, which leaves cattle weak and listless. Heavy infestations can kill animals or seriously stunt their growth from blood loss alone.

This is serious, but ticks in Michigan are nothing new. The difference now is that our uninvited guests’ asexual reproduction and livestock obsession pose serious new challenges.

The Asian longhorn tick is much less focused on humans, with no confirmed disease transmissions to people in the U.S. so far. That doesn’t mean it can’t happen, just that it hasn’t happened yet (or that we simply don’t know if it has).

The real threat is to Michigan animals and livestock. These ticks can form massive infestations (thousands per animal), leading to blood loss, disease, and mortality rates of 10% to 15%. Yikes.

This makes them a much bigger threat to our farmers than to hikers and hunters.

Economically, we could be looking at potentially large agricultural losses due to reduced meat and milk production, increased veterinary costs, and expensive tick control measures. As if meat wasn’t expensive enough already!

For now, our best defense is vigilance. Protect your animals and livestock. Learn to identify these ticks. Check yourself, your dogs, and any other outdoor animals you have. Stay alert, stay informed, and don’t let these little bastards take over.

Tom Zandstra is a passionate outdoorsman and CEO of The Fair Chase. Follow him on X @TheFairChase1.