Owosso — There’s a castle downtown in a park next to the Shiawassee River. It shines yellow in the sun, slate roof turrets reaching toward the sky. It’s not at all like the other buildings in Owosso. Where did it come from?

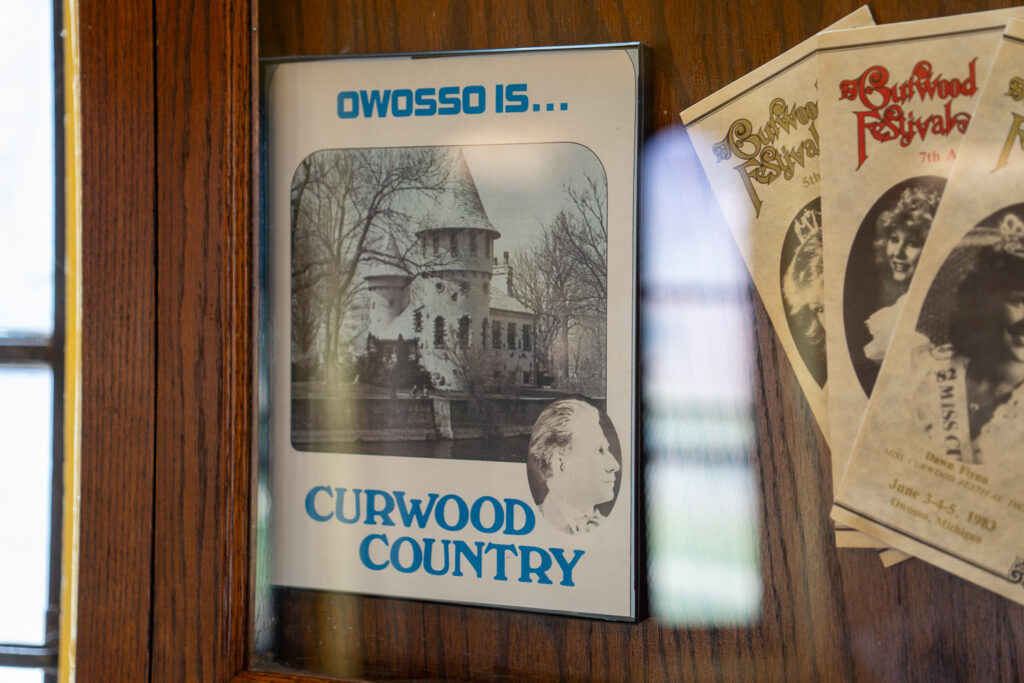

Welcome to Curwood Castle, the creation of famed Michigan author James Oliver Curwood.

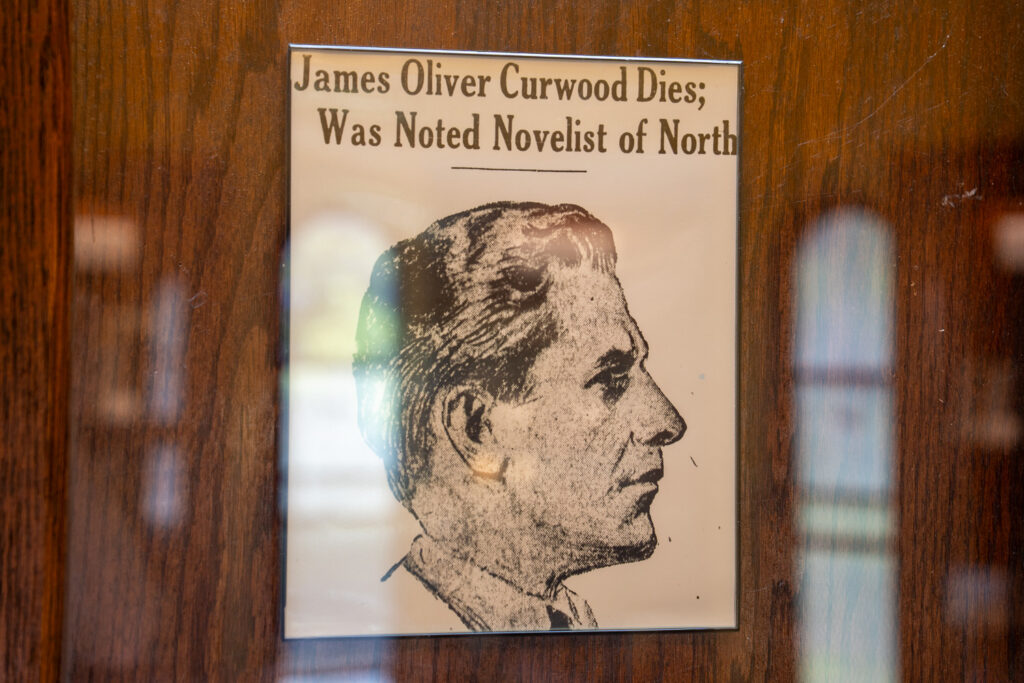

At the time of his death in 1927, Curwood was the highest paid author in the world. He published dozens of books, and over 200 short stories and articles. His 1919 novel, “The River’s End,” sold more than 100,000 copies.

Born in Owosso in 1878, Curwood was very American, a real Michigander, from a time when the Midwest still felt rugged. He was an outdoorsman and adventurer, known for his trips into the wilderness, while also being a man of letters.

He studied at U-M for two years, before dropping out and moving to Detroit to become a reporter for the Detroit News-Tribune. He began selling his stories then, but his big inspiration came when the Canadian government hired him to travel the far northern wilderness of the country and write about his journey.

He traveled north in 1907, the first of several months-long journeys throughout his life. Most of Curwood’s stories are inspired by and set in the vast expanse along the Hudson Bay. He found his artistic home in the wilderness and drew from it constantly.

After making his fortune and touring Europe for a time, he returned home to Owosso in 1924 and built his castle. Styled after an 18th-century Norman Chateau, it presents an iconic form, distinctive and flamboyant in otherwise humble surroundings.

It’s an incredible pad, filled with bearskin rugs and taxidermied moose heads. Thick wooden doors, painted stucco siding, leaded glass windows, a tower, and multiple turrets. Circular ship’s windows, typewriters, curved staircases.

It belongs in an episode of MTV Cribs, but now it functions as a museum for Curwood’s legacy. Glass display cases show artifacts, photographs, and news clippings from his life.

This is fitting, in a way, because Curwood never lived at the castle. It was his writing studio, a place to sequester himself away and type out stories. He lived with his family in a house on the other side of the river and would trek over daily to write.

One can imagine spending countless hours there, poring over typewritten manuscripts. The castle feels like a country estate, fitting for a man with a naturalistic reputation, even now that Owosso has built up around it.

The soft sounds of the river out the windows, the trees blowing in the wind. When you’re in there, you’re in a different realm. It has that rare feeling, which only distinctive buildings can possess, of the interiority of the mind of the man who built it.

Curwood lived an incredible life. He achieved fame and fortune with only his words, the memories and inspiration of his travels. He had a family, a beautiful wife and children. Famous people sought him out, royalty even—there’s a prominent photo of Curwood with the Crown Prince of Germany featured.

Yet, his legacy is lesser known in the modern age than similar figures like Ernest Hemingway. Perhaps because he was so productive that his legacy burned itself out.

His stories made their way to Hollywood and were made into over 100 movies, the bulk of them from the 1930s to the 1950s. They stretch from the silent era into the 1950s—the 1953 film “Back to God’s Country,” starring Rock Hudson, was the most popular.

Universally, they’re nature adventure films, often pulpy in style. More popular entertainment, less acclaimed by critics, another reason why you rarely hear of them today.

Looking down the list, it was Curwood mania in the golden age of Hollywood, but then the list drops off. Tastes changed, the blockbuster era began, and Curwood was left to the past.

It’s a shame, because Curwood’s stories present the sort of complicated moral ambiguity that Hollywood loves these days. “The River’s End” is a tale about a convict who takes the identity of the dead lawman who came after him—a conflicted, tense, yet masculine story that no Hollywood writers’ room remembers how to do.

Curwood died in 1927, bitten by an unknown animal in Florida and fatally infected. His castle remains, though his legacy is largely forgotten. It shouldn’t be, though, and perhaps this son of Michigan can find new fame.

Take a lesson from history, screenwriters. Curwood adaptations were gold once, and they could be again.

Bobby Mars is art director of Michigan Enjoyer. Follow him on X @bobby_on_mars.