Have you ever looked around and thought off-handedly, what in the H-E-double hockey sticks is going on around here? Are folks really asleep at the wheel? Is there something in the water?

Well, technically, there is.

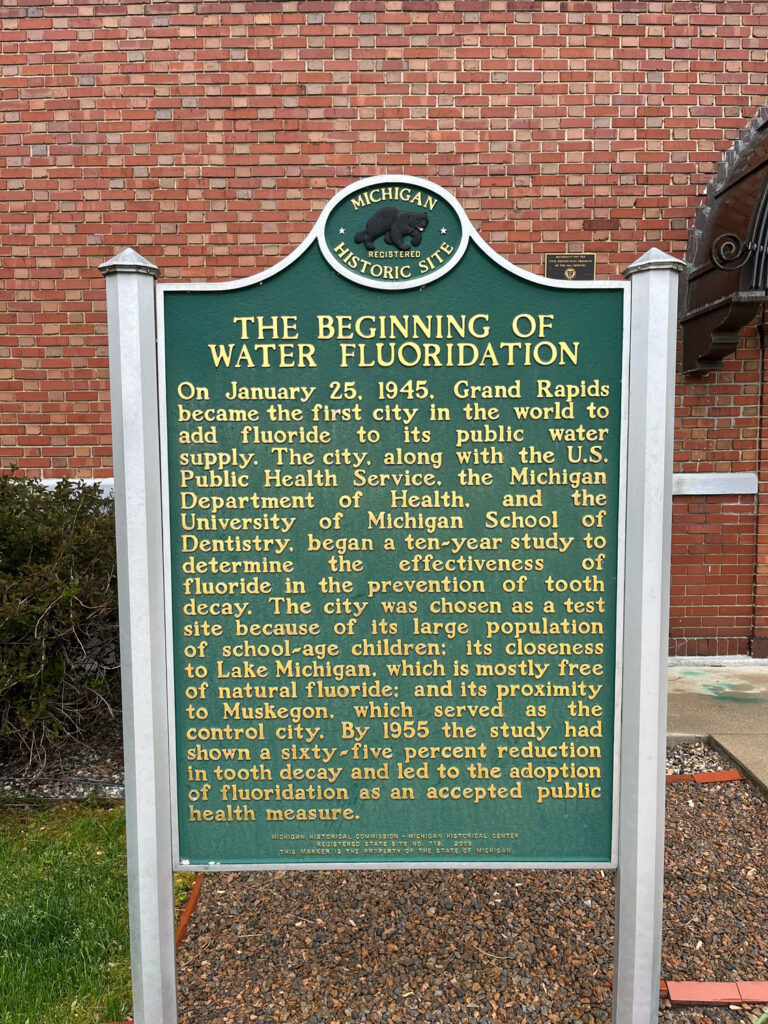

As of 2019, nearly 90% of Michiganders maintain access to fluoridated drinking water, more than 6.5 million people. Over 70% of Americans drink fluoridated water. But just 80 years ago, only one city in America had it, and that city was Grand Rapids.

Back in the 1840s, before the now-defunct Grand Rapids Hydraulic Company, it was said the citizens of Grand Rapids could dig a few feet into the ground to find fresh water. We had pipes flowing from fresh springs. Not quite the same picture these days.

Prior to the start of the great Grand Rapids fluoridated water experiment, there were discoveries about the effects of fluoride. If you search the history of fluoride, timelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are some of the first results.

The cookie-cutter version goes like this: People in poor communities with naturally high levels of fluoride in their drinking water had stained teeth that were strangely resistant with tooth decay.

In 1942, Dr. Henry Trendley Dean deemed fluoride was safe, and, in 1945, fluoridation program trials begin in American cities. The first to sign up? Grand Rapids.

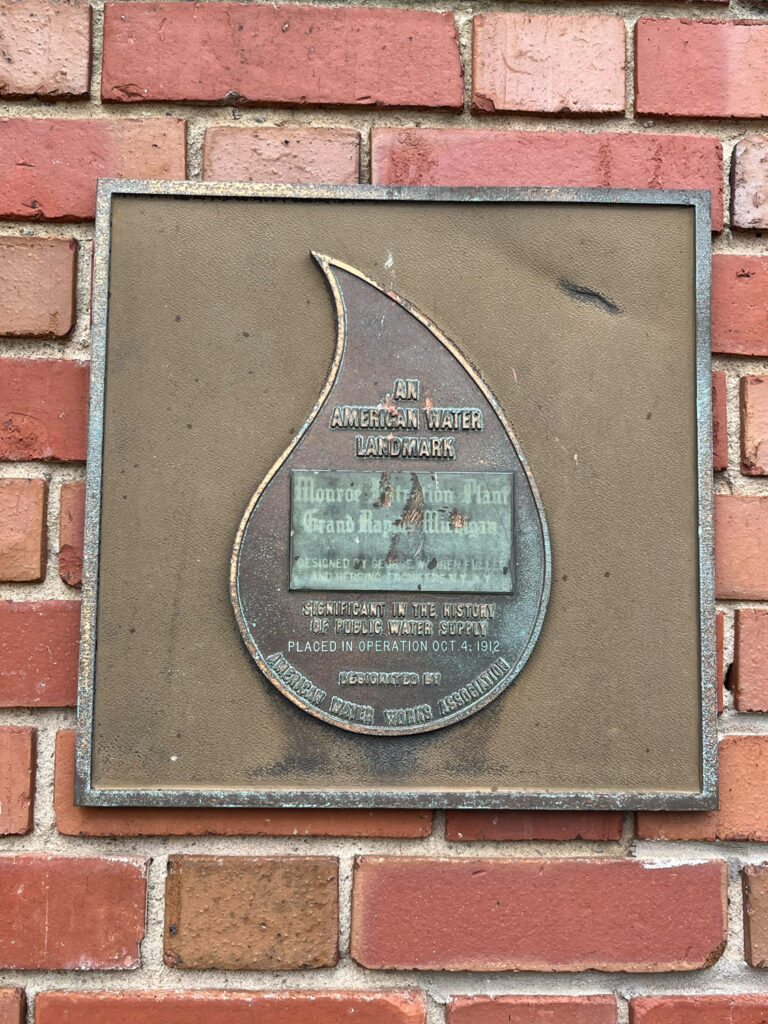

It was Jan. 25, 1945. Workers at the Monroe Water Filtration Plant fed powdered sodium fluoride, an aluminum byproduct, into the public system and out to every citizen of Grand Rapids for the start of what was to be a 15-year study. Muskegon was set to remain the control city, as they both drew fluoride-free water from Lake Michigan.

Scientists, researchers, dentists, and more flooded the state to examine the mouths of students lining up in schools.

Six years into the study, the announced positive results pressured Muskegon city officials into exiting the 15-year scientific study early, embracing fluoride for its community water.

Despite epidemiological studies of the non-dental effects of fluorine being extremely few and far between, and early trials being abandoned before completion, most dentists agreed that water fluoridation was best for the health of children’s teeth and came without negative effects.

By the late 1950s, most opposition had dissipated quietly. Anti-fluoride campaigns were quickly and publicly dismissed in the U.S., pushing its speakers in medical and scientific communities to the fringe, except for one respected allergist from Detroit, George Waldbott.

Waldbott was a distinguished physician, publishing over 100 articles. He was also vice president of the American College of Allergists. Waldbott’s worry was that the concentration of fluoride could be potentially unsafe for certain members of the community, and that tracing the vague symptoms of fluoride poisoning would be extremely difficult.

Waldbott also asserted that top dental journals would not touch anything with an anti-fluoride stance, and that the American Medical Association’s fluoridation endorsement for the House of Delegates had been rushed.

He maintained that the experiment was an unprecedented expansion of power for public health officials to medicate entire communities for the sake of a few who would benefit, without research into how it accumulates in other parts of the body and the effects of said accumulation.

Fast forward to today: Outside of the United States, only a handful of other countries even fluoridate their water.

Fluoride is also commonly added to most toothpaste and various other dental products, while numerous foods are fumigated with fluoride chemicals, even showing up as fluoride compounds on fast food wrappers. Dental fluorosis has almost doubled in adolescents since 1983, though my local dentist’s secretary has never even heard of it.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has celebrated fluoride and designated Grand Rapids’ Community Water Fluoridation 75th Anniversary Day in 2020, while her citizens complain over their lack of choice. Our health and state officials do not address their suspicions of danger or critiques of fluoridation.

Some communities have had the courage to ask questions and stop chemically treating their water.

A federal judge last September ruled in a case against the EPA that the current level set by the EPA poses unreasonable risk of hazard to a child’s IQ from the fluoride in San Francisco’s drinking water.

Tanks of highly toxic fluorosilicic acid are transported from Florida’s fertilizer factories to water reservoirs throughout the country to be put into the public drinking water. Florida Surgeon General Dr. Joseph Ladapo spoke publicly against community fluoridation.

Former scientist William Hirzy has purported that arsenic present in FSA has likely contributed every year to hundreds of cases of lung and bladder cancer and that only pharmaceutical grade sodium fluoride should be added to drinking water.

Studies have shown fluoride exposure is associated with behavioral and neurological issues as well as autism symptoms.

The ability to have an open conversation about our public health shouldn’t be a controversial issue, or even a political one. When there is a divergence from the goal of protecting our well-being, especially that of our youth, one has to ask: Why?

Remember, fluoride isn’t free. Someone sold it then, and someone is selling it now. Do you know what you’re buying? Or who’s selling?

We haven’t even made it to the pineal gland yet, but you get the idea.

In 1952, Rep. James J. Delaney led a congressional committee that came to a conclusion ahead of its time.

“It is safe to say that fluoridation is mass medication without parallel in the history of medicine,” the committee’s report said.

Devinn Dakohta is a contributing writer for Michigan Enjoyer. Follow her on Instagram @Devinn.Dakohta and X @DevinnDakohta.