Hillsdale — It was 70 years ago that Hillsdale College’s football team scored the greatest win in school history. In a game it didn’t even play.

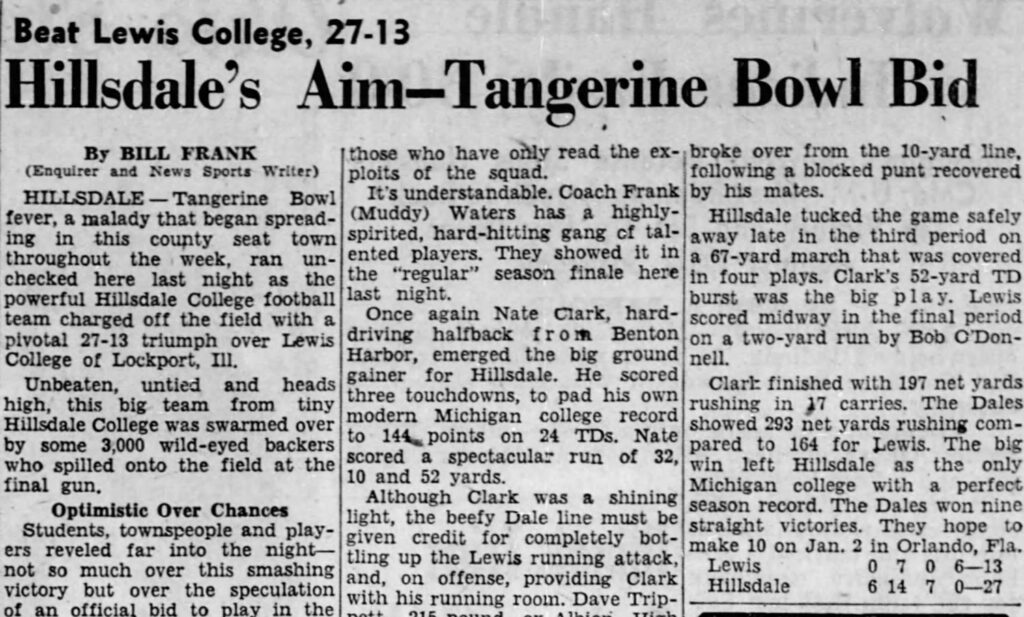

In the fall of 1955, the Dales were the best small-college football team in America. Under young head coach Frank “Muddy” Waters, Hillsdale rolled to a 9-0 record in the regular season and was invited to play in the prestigious Tangerine Bowl in Orlando.

There were very few college bowl games back then, especially for small schools like Hillsdale College, so it was an enormous deal to earn the invitation.

It was setting up to be their biggest game ever. The players would enjoy a week in the Florida sunshine and then, on January 2, 1956, they’d play in the first bowl game in school history. What a moment!

Then came the gut punch. When the Tangerine Bowl committee extended the invitation, it told Hillsdale’s coaches that the stadium owners wouldn’t allow race-mixing. You can play the game, they said, but you’ll need to leave your four black players at home.

What to do? Hillsdale had a choice to make. We can play in a bowl game, the biggest honor for any football team, and leave the four players behind. Or we can refuse the invitation, tell them to pound sand, and let the Tangerine Bowl know they can’t dictate who plays and who doesn’t.

For Hillsdale College, it was no choice at all. Coach Waters left it up to a vote of the team, and the team voted unanimously to tell the Tangerine Bowl to stick it.

We’re a team, they said. Either we all play or none of us play.

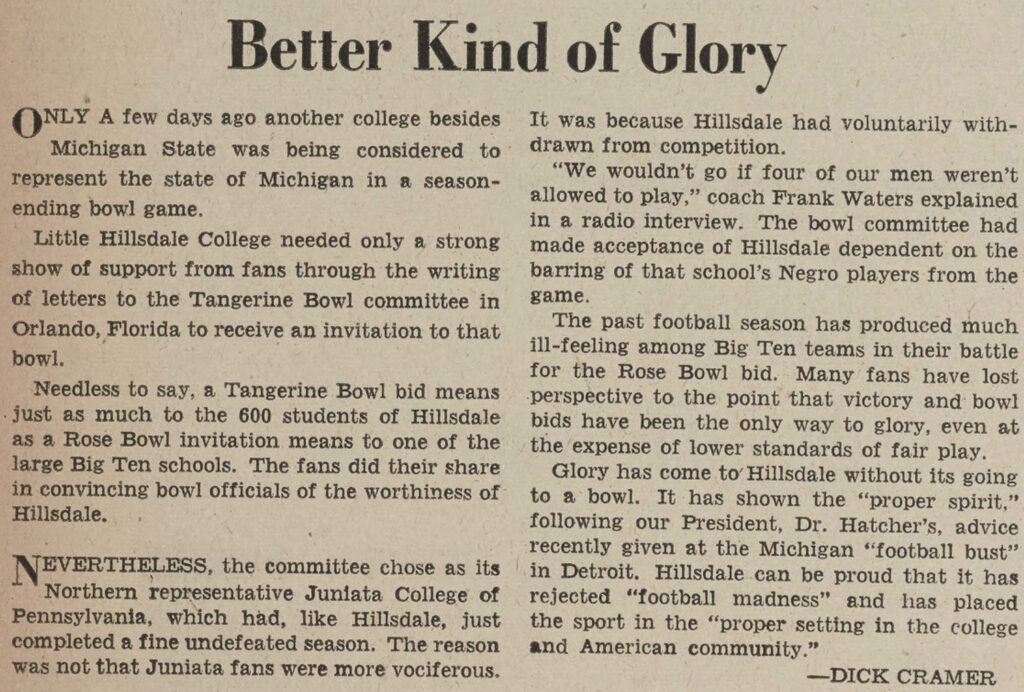

As an editorial writer for the Michigan Daily so eloquently put it, Hillsdale chose a “Better Kind of Glory.”

“Many fans have lost perspective to the point that victory and bowl bids have been the only way to glory, even at the expense of lower standards of fair play,” he wrote. “Glory has come to Hillsdale without going to a bowl.”

For the larger Hillsdale College community, the 1955 Tangerine Bowl incident has come to represent an affirmation of the school’s mission and goals, which were established 111 years before that game took place. And the 70th anniversary of the game is a fitting time for us to be celebrating it.

Hillsdale College was founded in 1844 by a group of Free Will Baptists and abolitionists who detested slavery, and the school’s mission from the start was to admit all students regardless of race, sex, or country of national origin. Unlike many other colleges and universities at the time, Hillsdale College admitted black students right from the start. It sent a higher percentage of students to fight in the Civil War than any college or university outside of the service academies.

“Equality” was not a buzzword at Hillsdale College. It was the mission.

So when the Tangerine Bowl incident cropped up a century later, it was a rubber-meets-the-road moment for the school. A bowl bid for their football team was a monumental accomplishment. Would Hillsdale’s leaders cast aside their mission for a brief moment to accept the glory that came with it, or would they stick up for their students?

They didn’t just talk the talk. When the moment came, they walked the walk.

The Tangerine Bowl story was fully told for the first time in a 2021 film by my documentary filmmaking class at Hillsdale College. It’s called, appropriately enough, “A Better Kind of Glory.”

The students did a spectacular job telling the story. Some of the basic details of the Tangerine Bowl incident were known in the Hillsdale College community, but until my students did this documentary, the story wasn’t fully known.

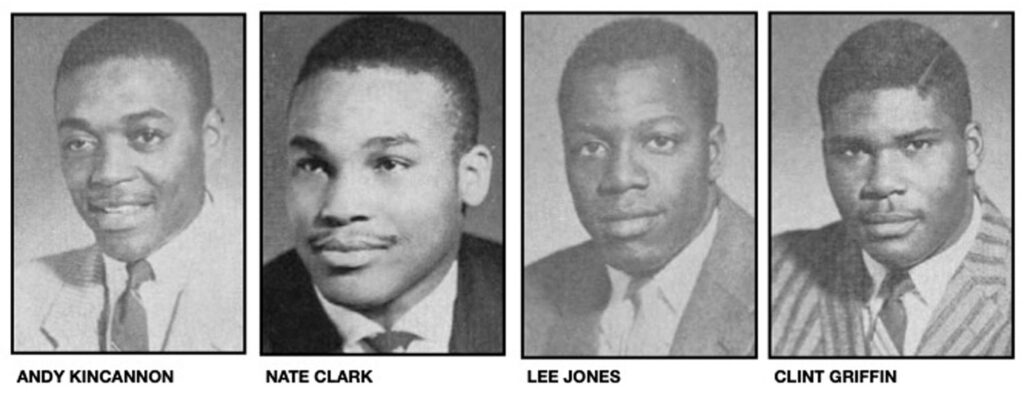

They were able to interview two of the players from the 1955 team, including one of the four black players on the team, Andy Kincannon (the only black player still alive). These men filled in the gaps and told us what really happened when the vote went down.

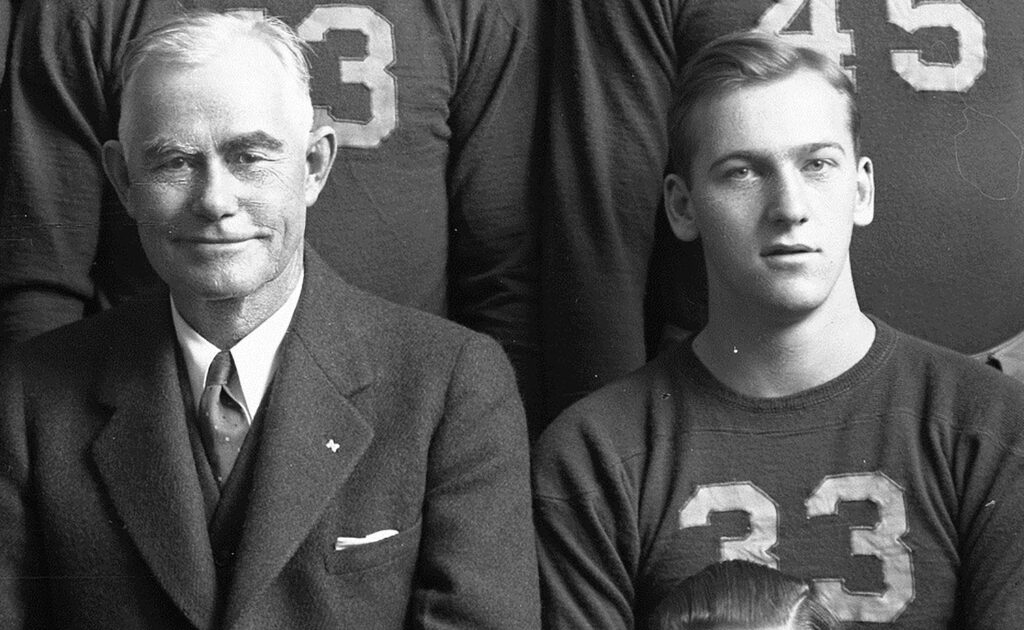

The story started in 1954, when Hillsdale hired a 31-year-old hotshot named Frank “Muddy” Waters to be its new football coach. He had great success that first season, leading the team to a 7-1-1 record and a league championship in 1954.

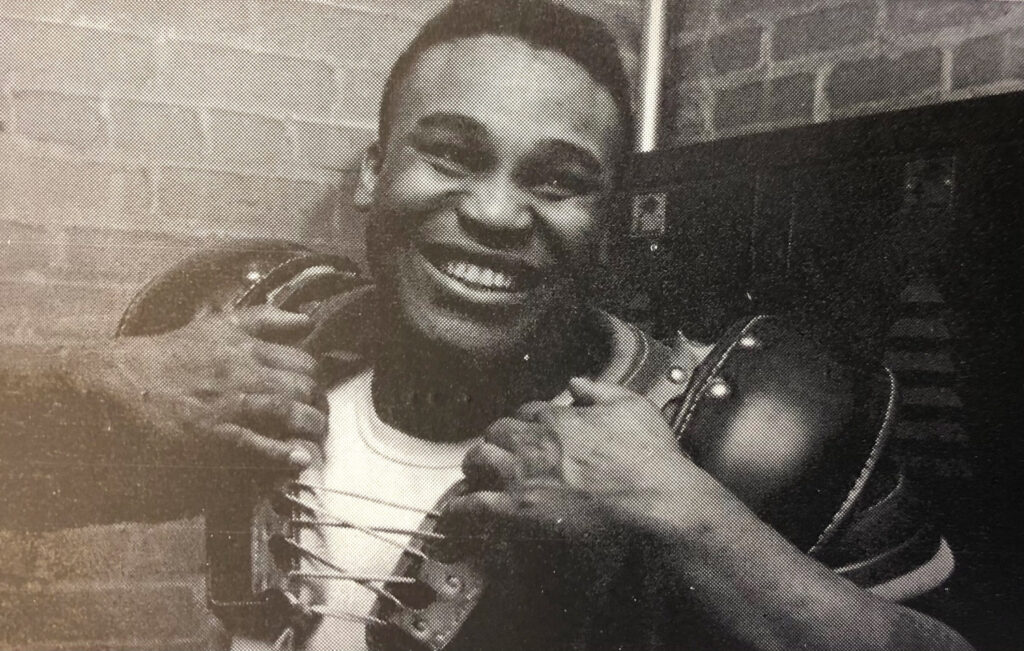

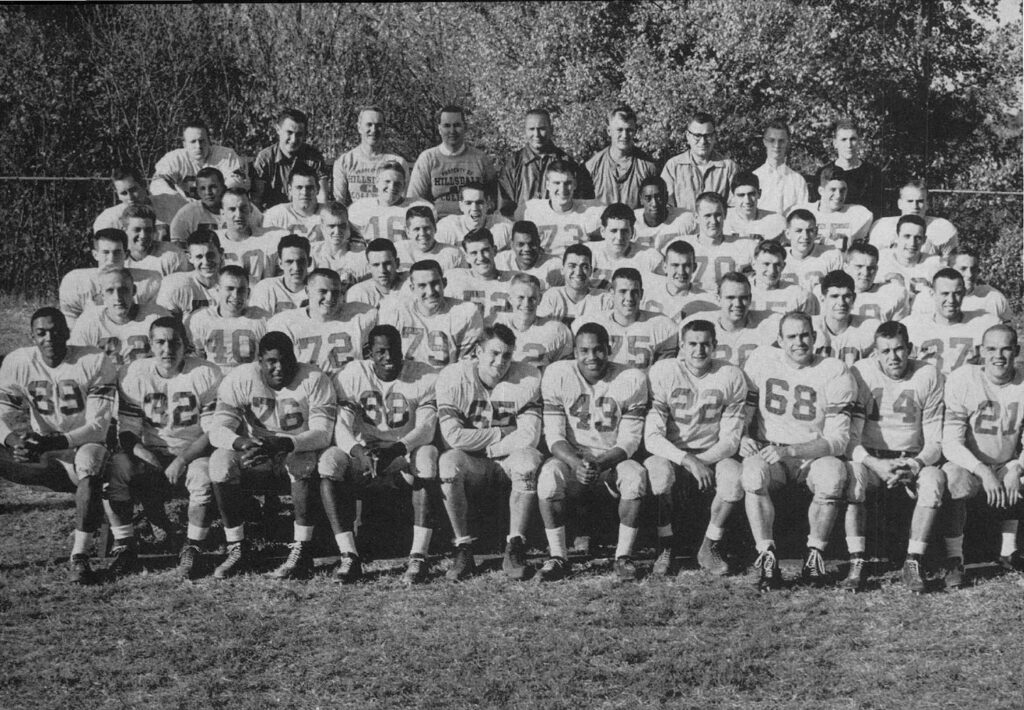

In 1955, though, the Dales went from good to great. They steamrolled everyone, finishing the regular season with a perfect 9-0 mark. Leading the team was a black running back from Benton Harbor named Nate Clark. He rushed for 949 yards and a mind-boggling 24 touchdowns in just nine games. Even today, Clark is considered one of the greatest players in Hillsdale history.

The three other black players on the team were also major contributors. Andy Kincannon was an All-League end from Detroit Chadsey who was one of the best pass-catchers in the conference. Lee Jones was a speedy wide receiver from Flint Northern. Clint Griffin was a bruising tackle from Detroit.

“Each year we just got better and better,” Kincannon said in the documentary. “Muddy Waters did a heck of a job recruiting and bringing people in and then making everybody feel comfortable and just developing a good football team.”

Late in the season, the Dales started attracting the attention of the Tangerine Bowl, a popular bowl game in Orlando which was founded in 1947 and regularly attracted the two best small-college teams in the country. Given the way they were bludgeoning everyone, it was a no-brainer that the Dales would receive one of the two invitations.

Muddy Waters himself went to Orlando to formally accept the invitation and negotiate the details, accompanied by Spike Hennessy, a trustee from the college.

Back home in Hillsdale, the campus community was in a frenzy over the possibility of playing in a bowl game in Florida. The college administration, the fans, the players—everyone was beyond giddy. “Hillsdale College Gets Bowl Fever,” read one headline.

When they got to Orlando, the committee did indeed extend the bowl invitation, but it came with a major string attached. The Tangerine Bowl stadium was controlled by the Orlando High School Athletic Association (OHSAA), which had a rule that said no race-mixing was allowed in any sporting event there.

Muddy wasn’t deterred. He and Spike Hennessy spent a full week in Orlando in early December lobbying the committee, pleading with them to get the OHSAA to make an exception for the Dales. The coach got some politicians involved, getting letters from four governors and six U.S. Senators, all of whom made the case that Hillsdale’s entire team deserved to play in the game.

When Muddy and Spike returned to Hillsdale, they were confident they had made their case. They were certain the Tangerine Bowl committee would be able to get the rule changed.

A few days later, though, they got word that the rule wouldn’t be changed. The Dales were still invited to play in the Tangerine Bowl, but they had to leave their four black players home. Period.

“Muddy came in and talked to us, and he said, this is what is happening,” Kincannon said. “They don’t want us to play because they don’t want the other team to play against black guys.”

At this point, the administration or coaches at Hillsdale could have made the decision themselves whether to play the game or not. Instead, Muddy Waters left it to a vote of the players.

“Muddy came in and talked to us about that,” Kincannon said. “He said, ‘If you guys decide you don’t want to play, I can understand.’ And so we kind of looked at each other and you could hear in the background different guys saying, no, we won’t play, we won’t play. We had a meeting and it was just decided that if we all could not play, then nobody would play. We wouldn’t go to the bowl game.”

“As I understand it, my grandfather wanted it to be a team decision,” Muddy’s grandson, Frank Waters, said in the documentary. “And so he felt very comfortable that they’d come to the right decision. The team put it to a vote, and they elected not to go, which he was very proud of. I think that was one of his proudest moments in coaching.”

The players had so much to gain by playing in the game. A week in Florida. A week in the national spotlight. The thrill of playing in the first bowl game in school history.

Instead, they chose a better kind of glory. Because that’s what Hillsdale College is and what it’s always been.

Muddy called the Tangerine Bowl people and gave them the news. Hillsdale College ain’t coming. The game instead pitted Pennsylvania’s Juniata College against Missouri Valley College. It was an incredibly boring game that ended in a 6-6 tie.

It was poetic justice that nobody won the Tangerine Bowl that year.

It’s interesting to note that the Tangerine Bowl story closely mirrors a 1934 incident at the University of Michigan in which the Wolverines hosted Georgia Tech in a football game in Ann Arbor. Georgia Tech said it would only play the game if Michigan benched its only black player, a gifted athlete named Willis Ward.

In that case, the decision was made by one person, U-M athletic director Fielding H. Yost, and Yost gladly agreed to bench Ward for the game. That decision infuriated many people on the campus, including Willis Ward’s best friend on the team, a tall kid from Grand Rapids named Gerald R. Ford.

Fielding Yost did the wrong thing in 1934. Twenty-one years later, the players at Hillsdale College did the right thing.

It’s also interesting to note that the Tangerine Bowl is now called the Citrus Bowl, and in this year’s Citrus Bowl, a team from the state of Michigan is once again invited—with no strings attached. The Michigan Wolverines will be playing the Texas Longhorns on the same field and in the same stadium where Hillsdale College was told its entire team was not welcome.

Seeing as how it’s the 70th anniversary of that game, and seeing as how another team from Michigan will be playing there this year, wouldn’t it be a wonderful thing for the Citrus Bowl to invite some people from Hillsdale College to be there? Andy Kincannon, maybe? Recognize and honor them on the same field where they were once made to feel unwelcome.

That would truly be a better kind of glory.

Buddy Moorehouse teaches documentary filmmaking at Hillsdale College.